13 July 2025 to 16 May 2025

¶ Where does, or might, your streaming money go? · 13 July 2025 listen/tech

There's a whole chapter in my book about how royalty distribution from streaming music services works, and when I worked at Spotify I could run the entire service's actual usage through potential alternate distribution models to see how they would affect artists differently. You can't do that, and I can't anymore either.

But if you've requested your own streaming history from Spotify, and loaded it into Curio, you can at least explore how alternate distribution models might distribute your money to the artists † ‡ you love.

You can start with this query comparing the usual pro-rata scheme to one that distibutes each listener's money according to their individual listening-time per artist.

Here's the query:

To do this without access to proprietary business data, we have to make a couple legally-arbitrary assumptions about two key internal Spotify numbers.

One is the fraction of Spotify revenue, for your subscription country and type, that gets paid out to licensors. This is variously quoted as "more than two-thirds" or "about 70%" in the press, and the exact number depends in a complicated way on local statutory rates, licensor deals and even sometimes the complicity of specific labels or artists in Spotify's grim attempts to fractionally improve their own margins. You can make up your own mind about what you want to believe this number to be, and if your mind makes up some number other than 0.7, you should replace the 0.7 in the ??rates= line with your alternative.

The second number is the average number of plays (industry-defined as "you listened to at least :30 of a song, but it doesn't make any difference how much if it's at least that much") for your subscription country and type. One common public guess at this average across all Spotify listeners is 500 plays/month; total Spotify membership is weighted about 3:2 in favor of ad-subsidized "free" listeners over subscribers; Daniel Ek once said in public that premium listeners spend about 3x as much time listening as free listeners, on average. Putting these numbers together with math (not shown here) suggests a premium-user average somewhere around 800. If you don't like that 800, replace the 800 in that same line with whatever you like better.

The 10.99 in my example is the current monthly cost of a US Basic account, which I choose (in both the moral and exemplary senses) because Spotify is engaged in a disingenuous ongoing effort to define the nominal Premium account as a supposedly-equal-value bundle of music and audiobooks so that they don't have to pay as much in music-publishing royalties. In this particular example I have filtered my listening history to data from calendar 2024, and thus have multiplied the monthly subscription and stream-count numbers both by 12. You could also take both 12s out and filter to any single month.

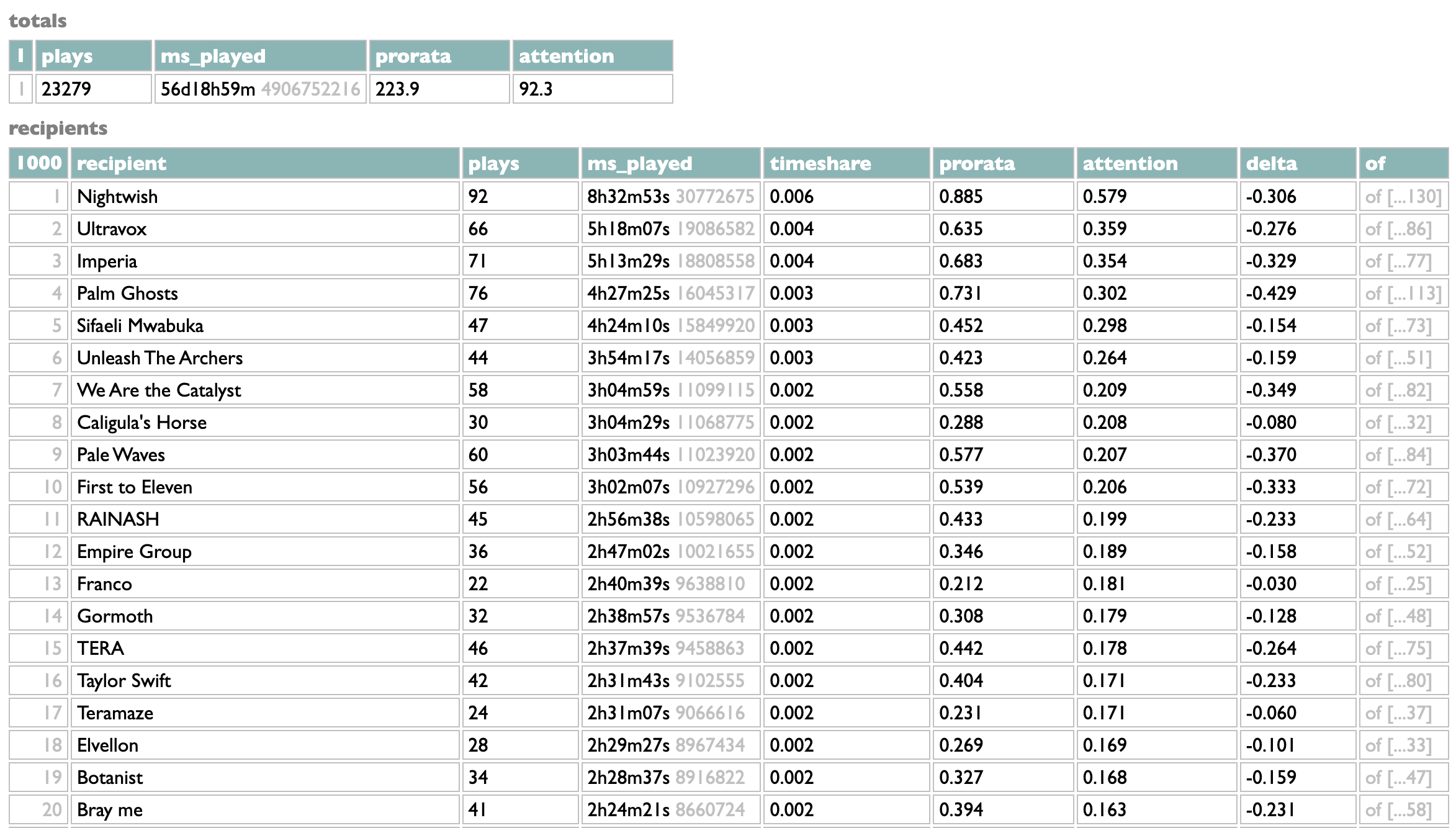

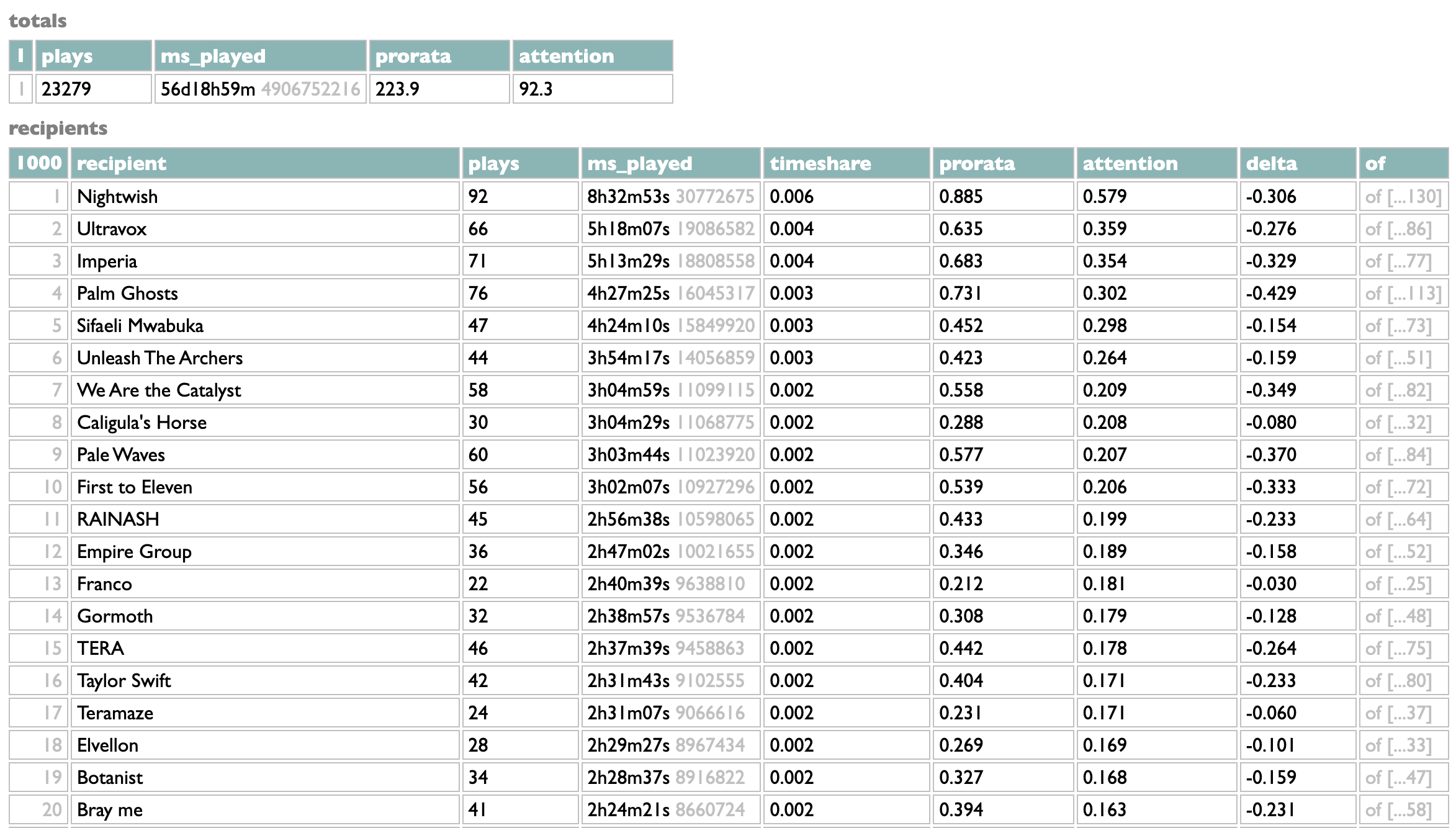

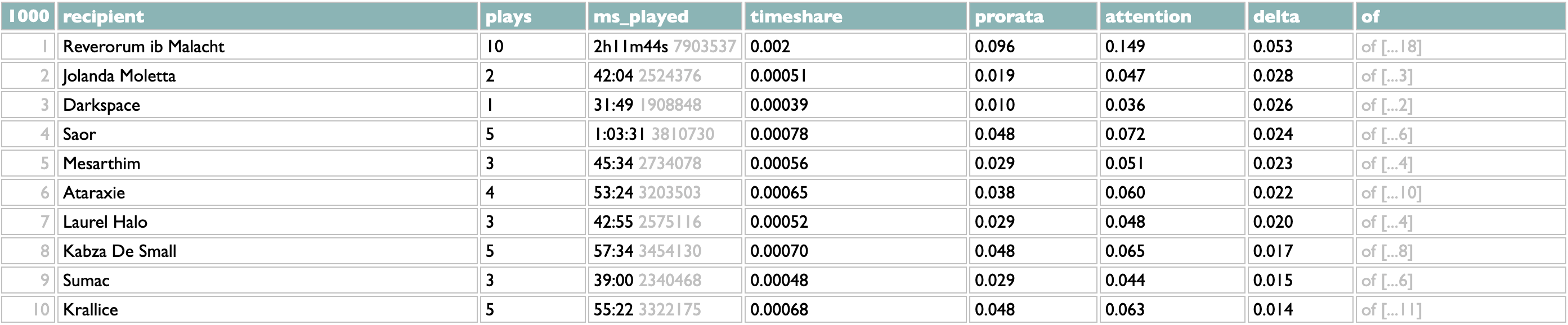

Using these numbers, here's what I get for my own 2024:

As I explain in the book, you can think of the pro-rata scheme as essentially allowing listeners who accumulate more than the average number of plays to reassign the leftover money from the people who play less than the average. User-centric models, whether based on plays or time, always only pay your artists with your money. With these hypothetical numbers, my subscription would have generated $92.30 in distributable money over the course of the year, and in the attention model that's exactly what my artists get in total. Because I happen to play very considerably more than the average listener, though, the pro-rata model allows me to commandeer almost an additional subscription and a half of money from less-active listeners, and my artists get a total of $223.90. The artists here at the top of my list benefit dramatically from this, at least proportionally, with some of them getting more than twice as much money because of me than they could get strictly from me.

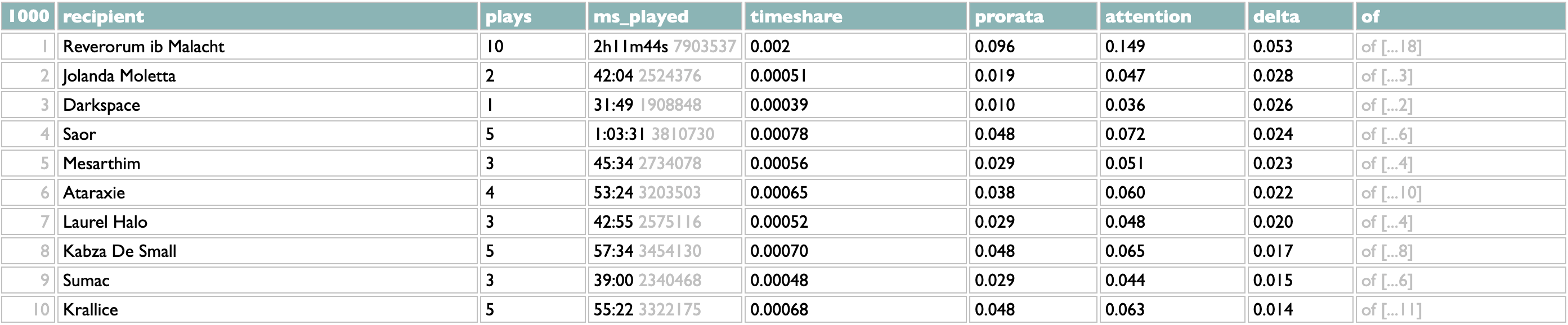

In my case this dynamic renders the plays-vs-time difference itself largely moot, but if we sort with #delta instead of #attention we can see that there are a few artists whose penchant for long tracks causes them to be under-rewarded by the current play-based scheme, and treated arguably more fairly by the time-based attention scheme:

In case it hasn't registered because I haven't bothered to implement currency-formatting, though, the decimal numbers in the prorata, attention and delta columns are all fractions of a dollar. My listening is even more obdurately broad than it is voluminous (I listened at least momentarily to 8374 different artists last year, and 5289 even if you only count the ones where I played at least :30 of at least one song), so no individual artist earns much from my streaming. Your artist amounts are likely to be higher. There's probably some selection bias such that people willing to go through the trouble of requesting their listening history, and signing up for an API key in order to use Curio, are more likely to also be more active listeners than the average. And more active listeners also tend, in general, to listen more broadly than less-active listeners. But I am, or at least I was back when I could check because of course I checked, an extreme case.

And because this is all just a query, not anything hard-coded into Curio itself, you can also experiment with the query itself to try other models if you want. I'm not really expecting you to have other streaming-royalty allocation schemes casually in mind, but I am hoping that showing you what you could try will make you slightly more likely to want to try things, in this domain or some other one you know and care about the way I know and care about music. I want a world in which the rules embedded in the systems that affect our money and our lives are intelligble to us, and subject to our verification and variation. I want us to want a better world, and we can't improve what we can't control, and we can't control what we can't understand or discuss.

† The critical caveat about the recipients here is that the current streaming services do not pay artists, they pay licensors. For independent artists, those licensors may be self-serve distributors like DistroKid or OneRPM that take only small fees and pass along most of the money to the artists. For artists on major labels, the label may keep most or even all of this royalty money, but in turn may have already paid the artist an advance against it. So the mechanics are complicated in ways that are out of both your and the streaming service's control.

‡ The trivial caveat about the query-modeling here is that the listening-history data Spotify lets you download does not identify each track's artist by unique ID, only by name. It's possible to get the correct unique artists by looking up the tracks within the query, e.g.:

but my own listening history has a lot of tracks and I didn't want to wait for that many API calls, so for this query I've chosen to tolerate the approximation of artist names. If you happen to really like multiple different artists with the exact same name, you'll see that their data gets combined in this query. I invite you into my experiment, but the invitation includes a hammer.

(And to admit my meta-interest, since I'm currently working on human computational agency and collective knowledge more than on streaming-royalty allocation, it's my belief that we should always insist that arguments based on data be supported by demonstration, not illustration. Shared understanding beats adversarial persuasion.)

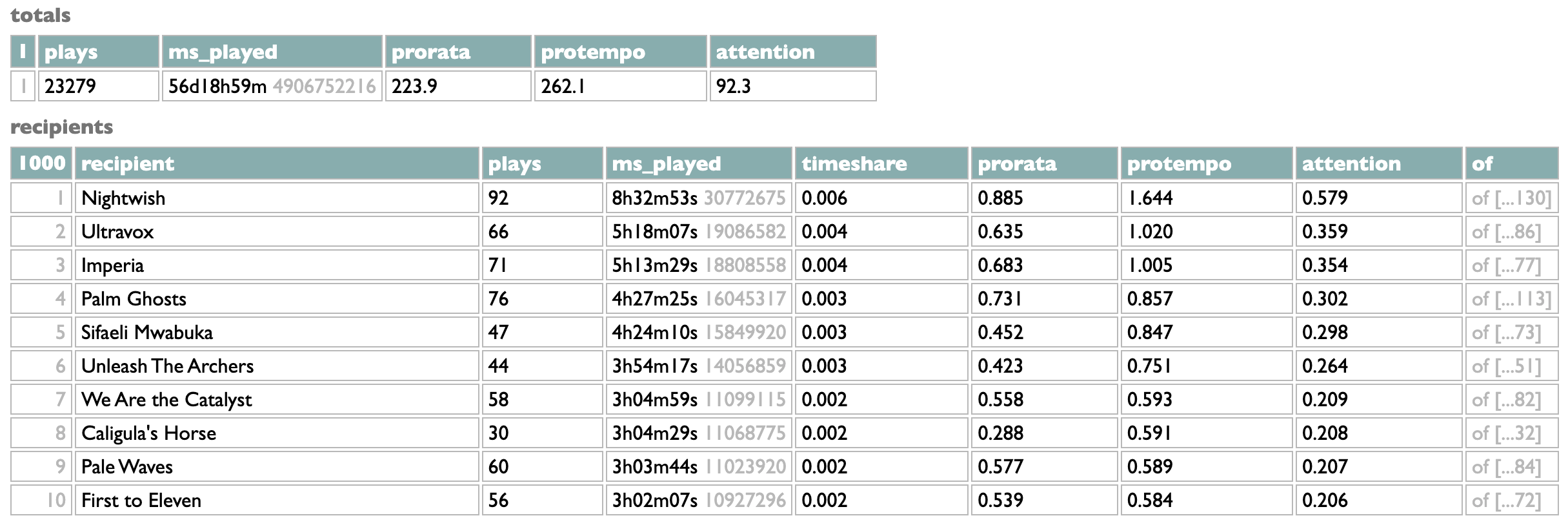

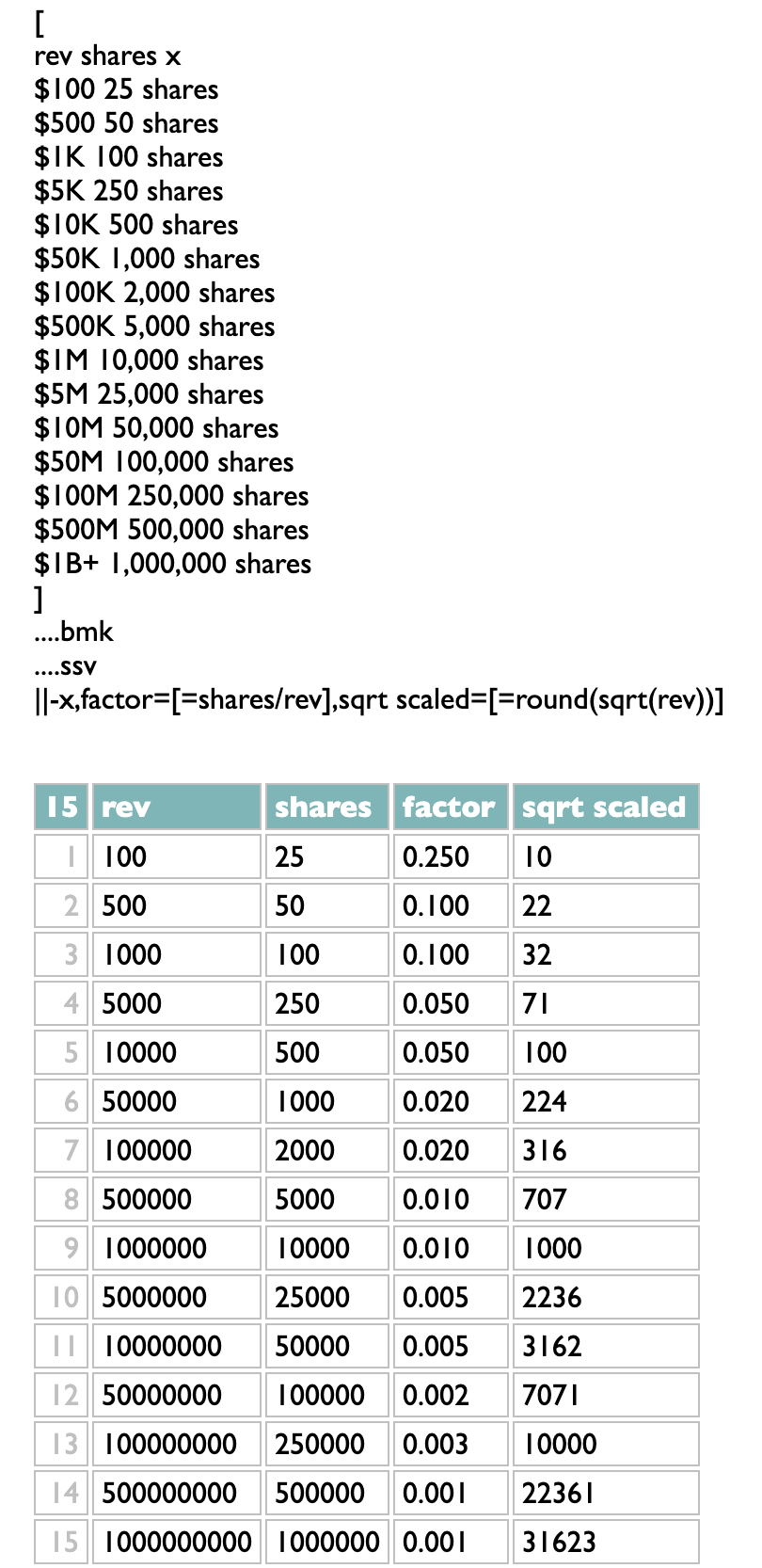

PS: To complicate this further, the scheme I actually endorse is pro-tempo, which is pro-rata but allocated by time instead of plays. This requires another guess at the average duration of a stream (not of a song), but if I put that guess at 3:00, my personal listening is even further above average in time than it is in plays, and the three-way comparison query shows me directing the allocation of $262.10, and almost 3x as much to my top artist as the supposedly-artist-centric attention scheme:

But if you've requested your own streaming history from Spotify, and loaded it into Curio, you can at least explore how alternate distribution models might distribute your money to the artists † ‡ you love.

You can start with this query comparing the usual pro-rata scheme to one that distibutes each listener's money according to their individual listening-time per artist.

Here's the query:

?listening history:~<[2024]

:(.master_metadata_album_artist_name)

??rates=(....||subscription=[=0.7*12*10.99],spu=[=800*12],rps=[=subscription/spu]),

totalms=(....ms_played,total),

pro rata=(

:ms_played>=30000:(.spotify_track_uri)

/recipient=master_metadata_album_artist_name,count=plays

.(....recipient,plays,prorata=(....plays,(rates.rps),product))

),

by user=(

/recipient=(.master_metadata_album_artist_name)

||ms_played=(..of....ms_played,total),

timeshare=[=ms_played/totalms],

subscription=(rates.subscription),

attention=[=timeshare*subscription],

-name,-key,-subscription,-count

)

?pro rata,by user//recipient #attention

||prorata=(.prorata;(0)),delta=[=attention-prorata]

||recipient,plays,ms_played,timeshare,prorata,attention,delta

...multi=(1),

totals=(

....plays=(....plays,total),

ms_played=(....ms_played,total),

prorata=(....prorata,total),

attention=(....attention,total)

),

recipients=_

:(.master_metadata_album_artist_name)

??rates=(....||subscription=[=0.7*12*10.99],spu=[=800*12],rps=[=subscription/spu]),

totalms=(....ms_played,total),

pro rata=(

:ms_played>=30000:(.spotify_track_uri)

/recipient=master_metadata_album_artist_name,count=plays

.(....recipient,plays,prorata=(....plays,(rates.rps),product))

),

by user=(

/recipient=(.master_metadata_album_artist_name)

||ms_played=(..of....ms_played,total),

timeshare=[=ms_played/totalms],

subscription=(rates.subscription),

attention=[=timeshare*subscription],

-name,-key,-subscription,-count

)

?pro rata,by user//recipient #attention

||prorata=(.prorata;(0)),delta=[=attention-prorata]

||recipient,plays,ms_played,timeshare,prorata,attention,delta

...multi=(1),

totals=(

....plays=(....plays,total),

ms_played=(....ms_played,total),

prorata=(....prorata,total),

attention=(....attention,total)

),

recipients=_

To do this without access to proprietary business data, we have to make a couple legally-arbitrary assumptions about two key internal Spotify numbers.

One is the fraction of Spotify revenue, for your subscription country and type, that gets paid out to licensors. This is variously quoted as "more than two-thirds" or "about 70%" in the press, and the exact number depends in a complicated way on local statutory rates, licensor deals and even sometimes the complicity of specific labels or artists in Spotify's grim attempts to fractionally improve their own margins. You can make up your own mind about what you want to believe this number to be, and if your mind makes up some number other than 0.7, you should replace the 0.7 in the ??rates= line with your alternative.

The second number is the average number of plays (industry-defined as "you listened to at least :30 of a song, but it doesn't make any difference how much if it's at least that much") for your subscription country and type. One common public guess at this average across all Spotify listeners is 500 plays/month; total Spotify membership is weighted about 3:2 in favor of ad-subsidized "free" listeners over subscribers; Daniel Ek once said in public that premium listeners spend about 3x as much time listening as free listeners, on average. Putting these numbers together with math (not shown here) suggests a premium-user average somewhere around 800. If you don't like that 800, replace the 800 in that same line with whatever you like better.

The 10.99 in my example is the current monthly cost of a US Basic account, which I choose (in both the moral and exemplary senses) because Spotify is engaged in a disingenuous ongoing effort to define the nominal Premium account as a supposedly-equal-value bundle of music and audiobooks so that they don't have to pay as much in music-publishing royalties. In this particular example I have filtered my listening history to data from calendar 2024, and thus have multiplied the monthly subscription and stream-count numbers both by 12. You could also take both 12s out and filter to any single month.

Using these numbers, here's what I get for my own 2024:

As I explain in the book, you can think of the pro-rata scheme as essentially allowing listeners who accumulate more than the average number of plays to reassign the leftover money from the people who play less than the average. User-centric models, whether based on plays or time, always only pay your artists with your money. With these hypothetical numbers, my subscription would have generated $92.30 in distributable money over the course of the year, and in the attention model that's exactly what my artists get in total. Because I happen to play very considerably more than the average listener, though, the pro-rata model allows me to commandeer almost an additional subscription and a half of money from less-active listeners, and my artists get a total of $223.90. The artists here at the top of my list benefit dramatically from this, at least proportionally, with some of them getting more than twice as much money because of me than they could get strictly from me.

In my case this dynamic renders the plays-vs-time difference itself largely moot, but if we sort with #delta instead of #attention we can see that there are a few artists whose penchant for long tracks causes them to be under-rewarded by the current play-based scheme, and treated arguably more fairly by the time-based attention scheme:

In case it hasn't registered because I haven't bothered to implement currency-formatting, though, the decimal numbers in the prorata, attention and delta columns are all fractions of a dollar. My listening is even more obdurately broad than it is voluminous (I listened at least momentarily to 8374 different artists last year, and 5289 even if you only count the ones where I played at least :30 of at least one song), so no individual artist earns much from my streaming. Your artist amounts are likely to be higher. There's probably some selection bias such that people willing to go through the trouble of requesting their listening history, and signing up for an API key in order to use Curio, are more likely to also be more active listeners than the average. And more active listeners also tend, in general, to listen more broadly than less-active listeners. But I am, or at least I was back when I could check because of course I checked, an extreme case.

And because this is all just a query, not anything hard-coded into Curio itself, you can also experiment with the query itself to try other models if you want. I'm not really expecting you to have other streaming-royalty allocation schemes casually in mind, but I am hoping that showing you what you could try will make you slightly more likely to want to try things, in this domain or some other one you know and care about the way I know and care about music. I want a world in which the rules embedded in the systems that affect our money and our lives are intelligble to us, and subject to our verification and variation. I want us to want a better world, and we can't improve what we can't control, and we can't control what we can't understand or discuss.

† The critical caveat about the recipients here is that the current streaming services do not pay artists, they pay licensors. For independent artists, those licensors may be self-serve distributors like DistroKid or OneRPM that take only small fees and pass along most of the money to the artists. For artists on major labels, the label may keep most or even all of this royalty money, but in turn may have already paid the artist an advance against it. So the mechanics are complicated in ways that are out of both your and the streaming service's control.

‡ The trivial caveat about the query-modeling here is that the listening-history data Spotify lets you download does not identify each track's artist by unique ID, only by name. It's possible to get the correct unique artists by looking up the tracks within the query, e.g.:

listening history :@<=10

||id=(....spotify_track_uri,([:]),split:@3)

/artist=(.other tracks.(.artists:@1))

||id=(....spotify_track_uri,([:]),split:@3)

/artist=(.other tracks.(.artists:@1))

but my own listening history has a lot of tracks and I didn't want to wait for that many API calls, so for this query I've chosen to tolerate the approximation of artist names. If you happen to really like multiple different artists with the exact same name, you'll see that their data gets combined in this query. I invite you into my experiment, but the invitation includes a hammer.

(And to admit my meta-interest, since I'm currently working on human computational agency and collective knowledge more than on streaming-royalty allocation, it's my belief that we should always insist that arguments based on data be supported by demonstration, not illustration. Shared understanding beats adversarial persuasion.)

PS: To complicate this further, the scheme I actually endorse is pro-tempo, which is pro-rata but allocated by time instead of plays. This requires another guess at the average duration of a stream (not of a song), but if I put that guess at 3:00, my personal listening is even further above average in time than it is in plays, and the three-way comparison query shows me directing the allocation of $262.10, and almost 3x as much to my top artist as the supposedly-artist-centric attention scheme:

The computer is a data knife. I've been using computers to cut up data since I first got one with enough memory to hold data in the late 1980s. The ergonomics of doing this, however, have been uniformly poor the whole time. Spreadsheets are fine for a certain subset of data tasks, kind of like a bagel-cutter is good for slicing a certain subset of foods. Most database software is structurally industrial-scale, more like a bread-slicing machine than a knife.

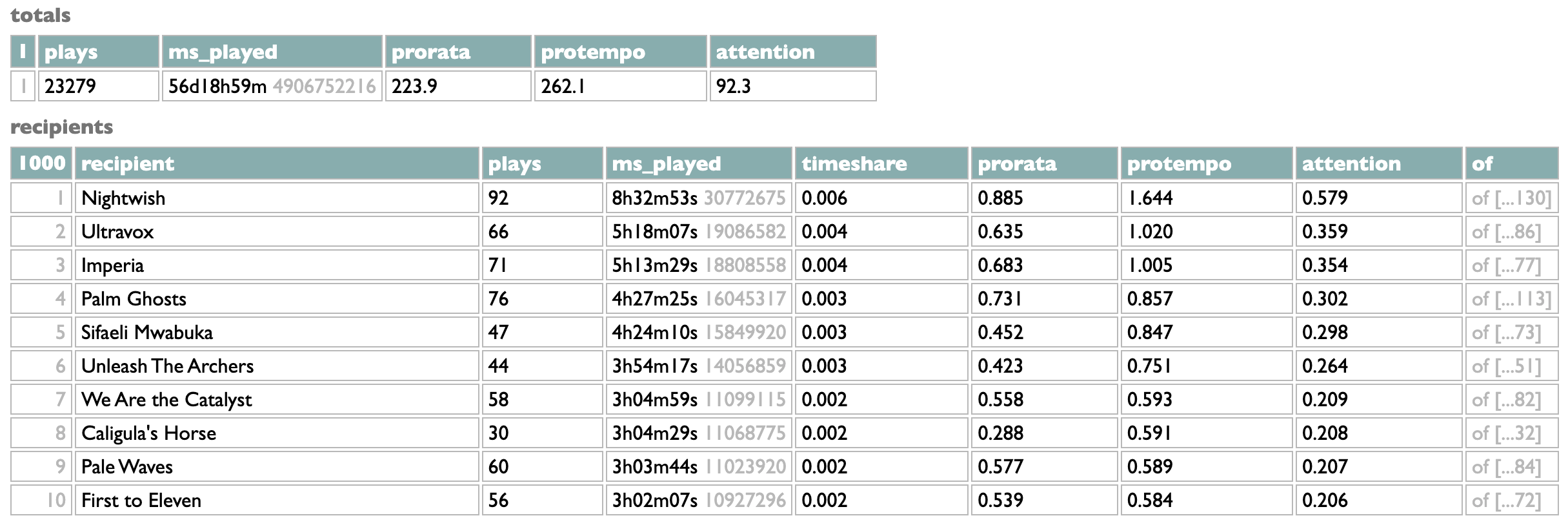

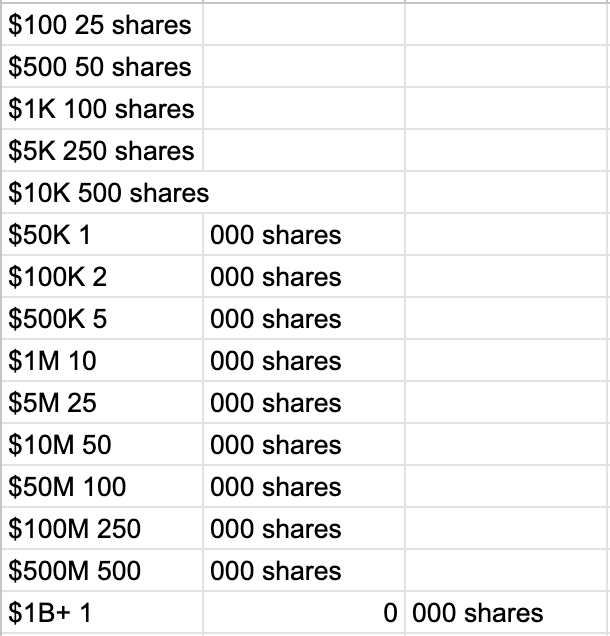

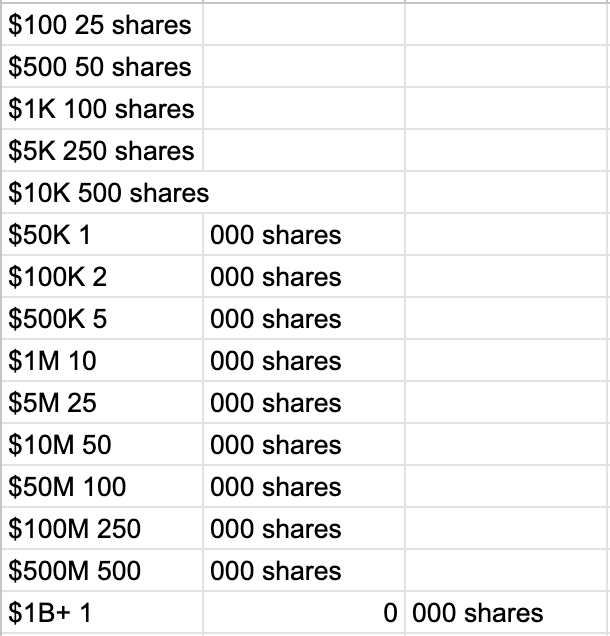

A friend just sent me this tiny table of numbers:

$100 25 shares

$500 50 shares

$1K 100 shares

$5K 250 shares

$10K 500 shares

$50K 1,000 shares

$100K 2,000 shares

$500K 5,000 shares

$1M 10,000 shares

$5M 25,000 shares

$10M 50,000 shares

$50M 100,000 shares

$100M 250,000 shares

$500M 500,000 shares

$1B+ 1,000,000 shares

I pasted it into Google Sheets, did Data > Split text to columns, and got this:

Not useful.

But do we still need data knives if we have AI? Our agents can cut our data up into safe bite-sized pieces for us, can't they? Hold still and open your mouth. I gave this table to Claude and asked "does this look right?"

My questions there are verbatim, Claude's responses are condensed from multiple pages of earnest unhelpfulness. That may not be a dull knife, exactly, but I don't really want a cheerful knife with which I have to begin by arguing about the nature of sharpness.

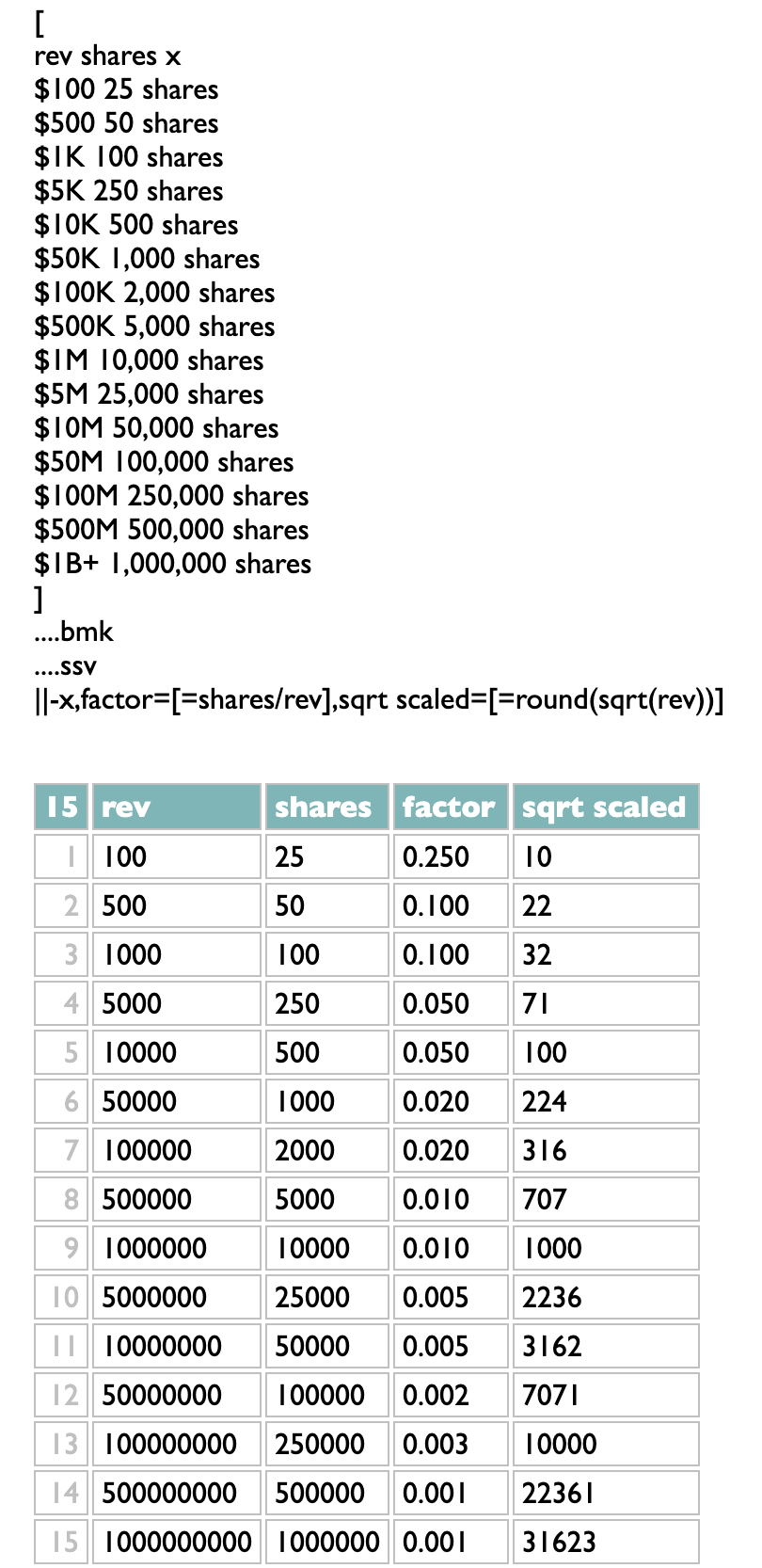

Part of my ambition for DACTAL is that it could be a better knife. The surgery we need here isn't exactly traumatic: expand the K/M/B shorthands into actual numbers, chop up this set of space-separated-values into labeled fields, check the math, maybe try an alternative scheme.

That isn't just a picture of numbers. Click it and you'll go to the cutting board where you can hack at them yourself. Or, if you prefer, some other data of your own.

Next I'm going to need some data tupperware.

A friend just sent me this tiny table of numbers:

$100 25 shares

$500 50 shares

$1K 100 shares

$5K 250 shares

$10K 500 shares

$50K 1,000 shares

$100K 2,000 shares

$500K 5,000 shares

$1M 10,000 shares

$5M 25,000 shares

$10M 50,000 shares

$50M 100,000 shares

$100M 250,000 shares

$500M 500,000 shares

$1B+ 1,000,000 shares

I pasted it into Google Sheets, did Data > Split text to columns, and got this:

Not useful.

But do we still need data knives if we have AI? Our agents can cut our data up into safe bite-sized pieces for us, can't they? Hold still and open your mouth. I gave this table to Claude and asked "does this look right?"

Claude: The scaling seems quite aggressive - the share awards increase much faster than the earnings.

glenn: You say "the share awards increase much faster than the earnings", but isn't it exactly the reverse?

Claude: You're absolutely right - I made an error in my analysis. The share awards increase much slower than the earnings, not faster. This creates a regressive structure where higher earners get a smaller percentage of their earnings in shares.

glenn: If higher earners get a smaller percentage, isn't that literally a progressive scheme?

Claude: You're absolutely correct again - I have my definitions backwards!

My questions there are verbatim, Claude's responses are condensed from multiple pages of earnest unhelpfulness. That may not be a dull knife, exactly, but I don't really want a cheerful knife with which I have to begin by arguing about the nature of sharpness.

Part of my ambition for DACTAL is that it could be a better knife. The surgery we need here isn't exactly traumatic: expand the K/M/B shorthands into actual numbers, chop up this set of space-separated-values into labeled fields, check the math, maybe try an alternative scheme.

That isn't just a picture of numbers. Click it and you'll go to the cutting board where you can hack at them yourself. Or, if you prefer, some other data of your own.

Next I'm going to need some data tupperware.

¶ The Initiative to Cultivate Empathy · 11 July 2025

I think we can all agree that the United States has a problem. Due to historical deficiencies in our moral educational system, we have suffered an internal invasion of intolerance, xenophobia and racism. These corrosive sociopathies have now reached such critical levels that they are interfering with our ability to operate a humane progressive democracy. It is time to fix this.

It will be expensive, but I believe this effort is crucial for our national survival, so I propose budgeting approximately $75 billion to create the Initiative to Cultivate Empathy. This new federal agency will recruit Americans who feel, or performatively claim to feel, racism or intolerance towards other human beings. In order to help them overcome these handicaps, it will temporarily employ them, on a paid full-time basis, to seek out immigrants or people who look like they believe immigrants look. When they find such people, these agents will use the full power of federal authority to give them sandwiches, fresh fruit and low-calorie probiotic soda, and to talk to them to learn about their cultural identities, life challenges and traditional preferences in hip hop.

The Initiative will also take inspiration from the current administration's laudable willingness to spend money to house immigrants, or people who look like they believe immigrants look, or graduate students with opinions, and will build and operate a set of federal shelters, located where most needed, to provide comfortable transitional housing for newly arrived immigrants or other people in temporary need. These facilities will also run supportive services, such as classes so that agents who only speak English have the opportunity to learn another language, or dinner groups in which they can experience food that contains spices, or quiet rooms that contain large-print books about world history.

The goal of this Initiative is to produce a meaningful increase in the average level of compassion among those involved, and thus to strengthen all of American Society. You could think of this as the Mean New Deal.

But the official name will, again, be the

Initiative to

Cultivate

Empathy.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

It will be expensive, but I believe this effort is crucial for our national survival, so I propose budgeting approximately $75 billion to create the Initiative to Cultivate Empathy. This new federal agency will recruit Americans who feel, or performatively claim to feel, racism or intolerance towards other human beings. In order to help them overcome these handicaps, it will temporarily employ them, on a paid full-time basis, to seek out immigrants or people who look like they believe immigrants look. When they find such people, these agents will use the full power of federal authority to give them sandwiches, fresh fruit and low-calorie probiotic soda, and to talk to them to learn about their cultural identities, life challenges and traditional preferences in hip hop.

The Initiative will also take inspiration from the current administration's laudable willingness to spend money to house immigrants, or people who look like they believe immigrants look, or graduate students with opinions, and will build and operate a set of federal shelters, located where most needed, to provide comfortable transitional housing for newly arrived immigrants or other people in temporary need. These facilities will also run supportive services, such as classes so that agents who only speak English have the opportunity to learn another language, or dinner groups in which they can experience food that contains spices, or quiet rooms that contain large-print books about world history.

The goal of this Initiative is to produce a meaningful increase in the average level of compassion among those involved, and thus to strengthen all of American Society. You could think of this as the Mean New Deal.

But the official name will, again, be the

Initiative to

Cultivate

Empathy.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

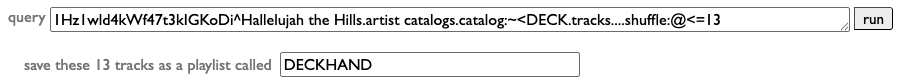

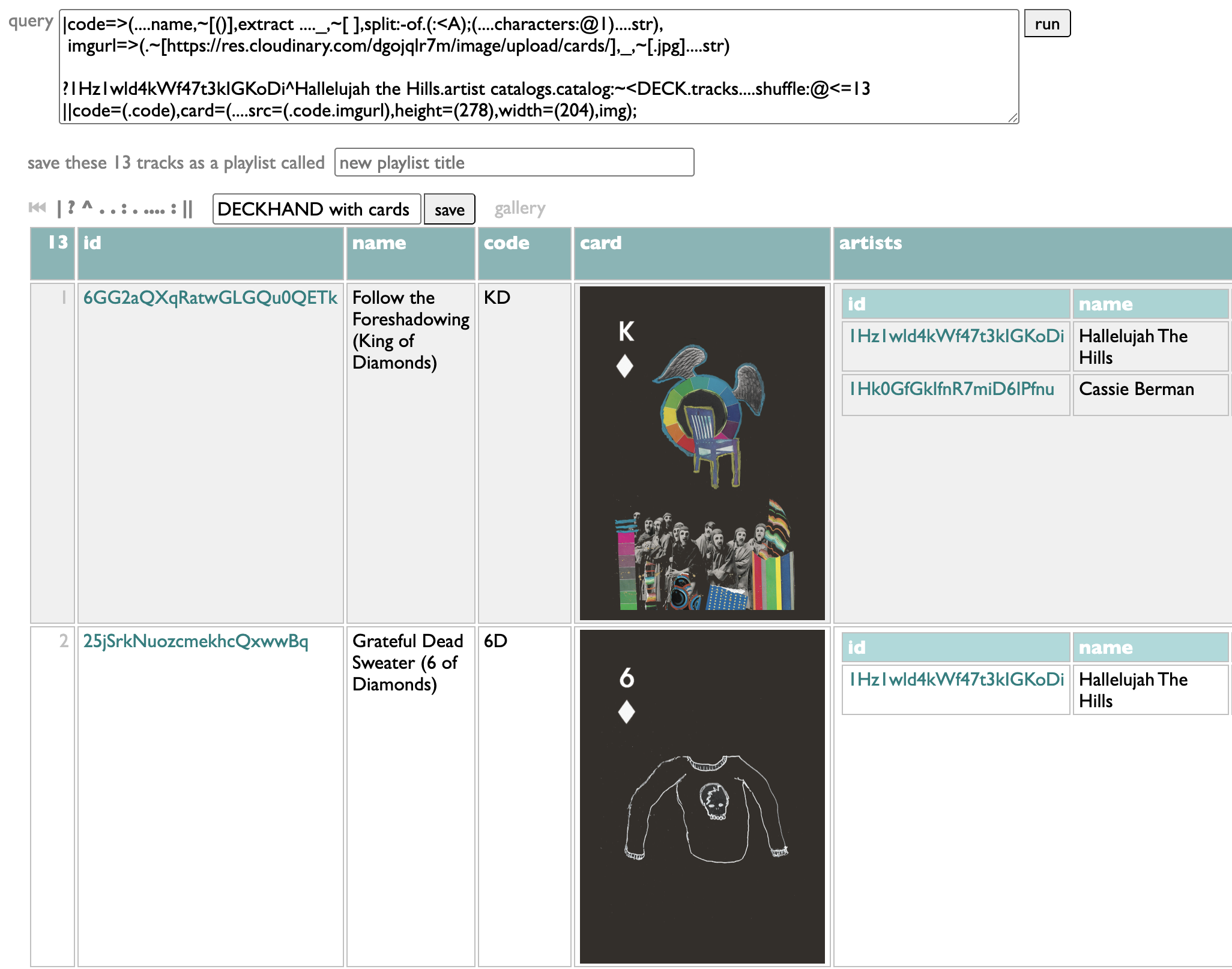

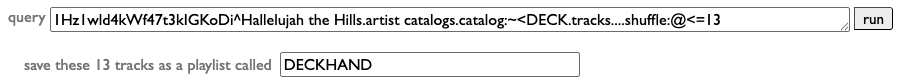

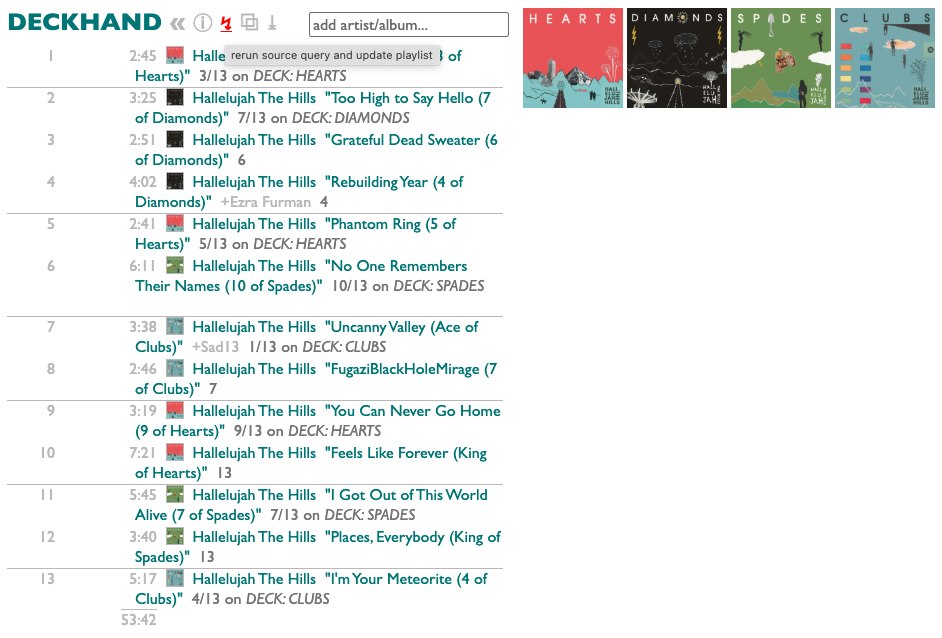

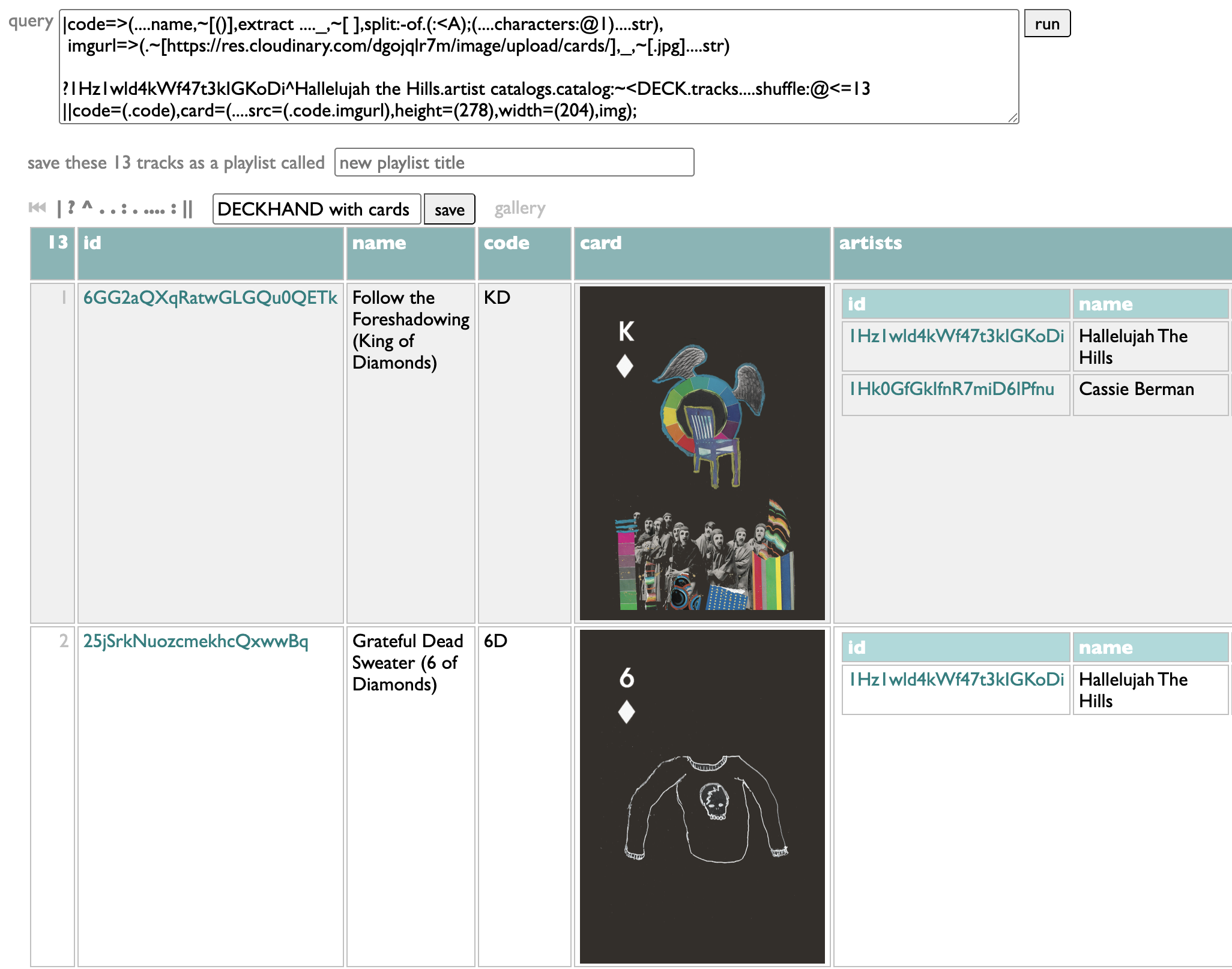

Hallelujah the Hills suggest picking random 13-song excerpts from their four-album (plus jokers) set DECK, and you can do that with a query in Curio.

Go to the Curio query page and paste in this query:

Run it, then put DECKHAND in the playlist-name blank, and hit Enter.

Now you not only have a playlist, but Curio remembers the query you made it with, so you can re-deal it whenever you're ready.

PS: Oh, Ryan points out that they made their own interactive version of his deck of actual cards here!

https://deck.hallelujahthehills.com/

We can even add the images into the query:

Go to the Curio query page and paste in this query:

1Hz1wld4kWf47t3kIGKoDi^Hallelujah the Hills.artist catalogs.catalog:~<DECK.tracks....shuffle:@<=13

Run it, then put DECKHAND in the playlist-name blank, and hit Enter.

Now you not only have a playlist, but Curio remembers the query you made it with, so you can re-deal it whenever you're ready.

PS: Oh, Ryan points out that they made their own interactive version of his deck of actual cards here!

https://deck.hallelujahthehills.com/

We can even add the images into the query:

|code=>(....name,~[()],extract ...._,~[ ],split:-of.(:<A);(....characters:@1)....str),

imgurl=>(.~[https://res.cloudinary.com/dgojqlr7m/image/upload/cards/],_,~[.jpg]....str)

?1Hz1wld4kWf47t3kIGKoDi^Hallelujah the Hills.artist catalogs.catalog:~<DECK.tracks....shuffle:@<=13

||code=(.code),card=(....src=(.code.imgurl),height=(278),width=(204),img);

imgurl=>(.~[https://res.cloudinary.com/dgojqlr7m/image/upload/cards/],_,~[.jpg]....str)

?1Hz1wld4kWf47t3kIGKoDi^Hallelujah the Hills.artist catalogs.catalog:~<DECK.tracks....shuffle:@<=13

||code=(.code),card=(....src=(.code.imgurl),height=(278),width=(204),img);

You don't have to treat the syntax design of a query language like a puzzle box, and certainly the designers of SQL didn't. SQL is more like a gray metal filing-cabinet full of manilla folders full of officious forms. I spent a decade formulating music questions in SQL, and I got a lot of exciting answers, but the process never got any less drab or any more inspiring. It never made me much want to tell other people that they should want to do this, too. It was always work.

I don't think this is just me. SQL may be more or less tolerable to different writers, but I feel fairly certain that nobody finds it charming. Whether anybody other than me will find DACTAL charming, I won't presume to predict, but every earnest work begins with an audience of one. DACTAL has an internal aesthetic logic, and using it pleases me and makes me want to use it more. And makes me care about it. I never cared about SQL. I never wanted to improve it. It never seemed like it cared about itself enough to want to improve.

In DACTAL, I feel every tiny grating misalignment of components as an opportunity for attention, adjustment, resolution. I pause in mid-question, and grab my tweezers. Changing reverse index-number filtering from :@-<=8 to :@@<=8 eliminates the only syntactic use of - inside filters; this allows filter negation to be switched from ! to - to match all the other subtractive and reversal cases; this frees up ! to be the repeat operator, eliminating the weird non-synergy between ? (start) and ?? (repeat). ?messages._,replies?? seems to express more doubt about replies than enthusiasm. Recursion is exclamatory. messages._,replies!

The gears snap into their new places with more lucid clicks. I want to feel like humming while I work, not grumbling. Like I'm discovering secrets, not filing paperwork.

I don't think this is just me. SQL may be more or less tolerable to different writers, but I feel fairly certain that nobody finds it charming. Whether anybody other than me will find DACTAL charming, I won't presume to predict, but every earnest work begins with an audience of one. DACTAL has an internal aesthetic logic, and using it pleases me and makes me want to use it more. And makes me care about it. I never cared about SQL. I never wanted to improve it. It never seemed like it cared about itself enough to want to improve.

In DACTAL, I feel every tiny grating misalignment of components as an opportunity for attention, adjustment, resolution. I pause in mid-question, and grab my tweezers. Changing reverse index-number filtering from :@-<=8 to :@@<=8 eliminates the only syntactic use of - inside filters; this allows filter negation to be switched from ! to - to match all the other subtractive and reversal cases; this frees up ! to be the repeat operator, eliminating the weird non-synergy between ? (start) and ?? (repeat). ?messages._,replies?? seems to express more doubt about replies than enthusiasm. Recursion is exclamatory. messages._,replies!

The gears snap into their new places with more lucid clicks. I want to feel like humming while I work, not grumbling. Like I'm discovering secrets, not filing paperwork.

In Query geekery motivated by music geekery I describe this DACTAL implementation of a genre-clustering algorithm:

The clustering in this version makes heavy use of the DACTAL set-labeling feature, which assigns names to sets of data and allows them to be retrieved by name later. That's what all the ?artistsx=, ?clusters= and similar bits are doing.

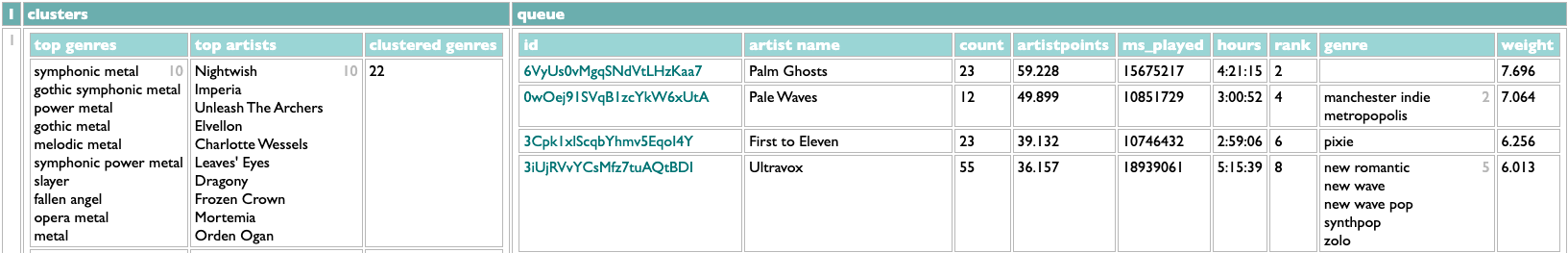

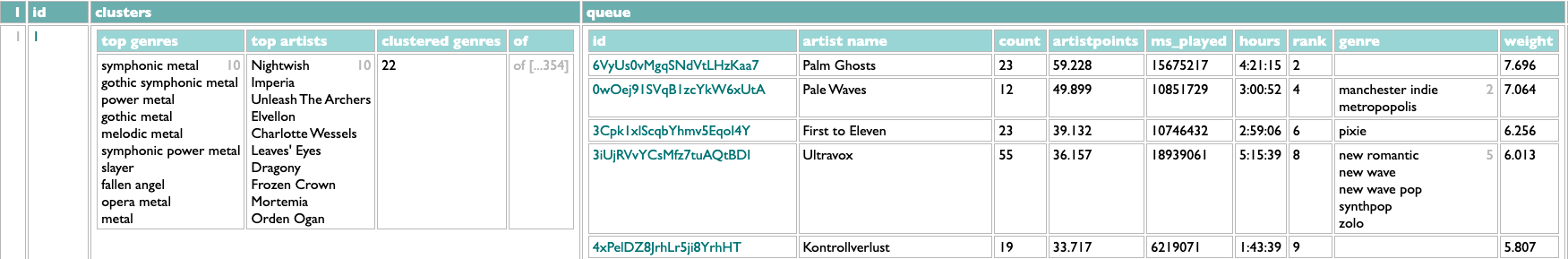

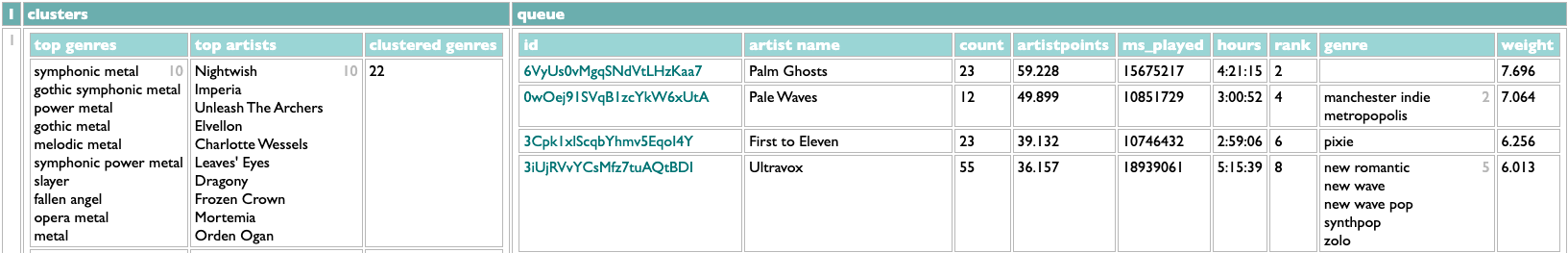

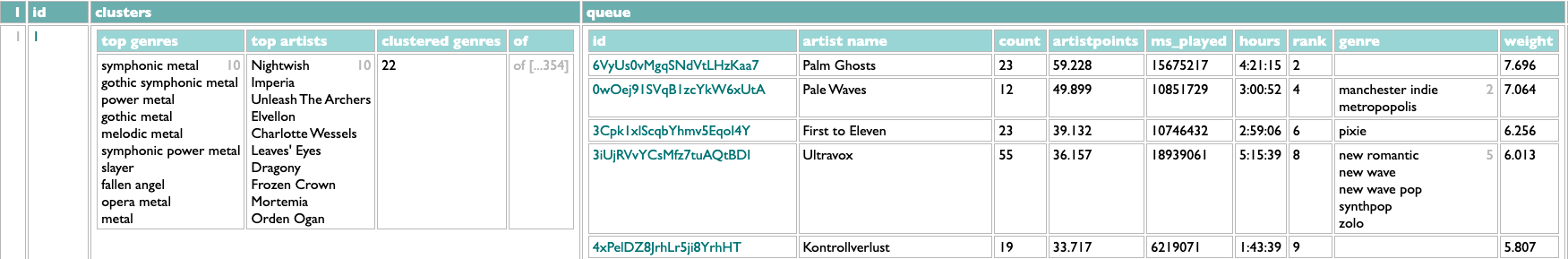

But it also uses DACTAL's feature for creating data inline. That's what the four-line block beginning with ...top genres= is doing. The difference between the two features is immediately evident if we try to scrutinize this query more closely by changing the ! at the end to !1 so it only runs one iteration. We get this:

That is, indeed, the first row of the query's results, and the lines in the query's ... operation map directly to the columns you see. But when I said I wanted to look at this query "more closely", I didn't mean I just wanted to see less of it. The crucial second piece of this query's clustering operation is the queue of unclustered artists, which gets shortened after each step. The query handles this queue by using set-labeling to stash it away as "artistsx" at two points in the query and get it back at two other points. This is useful, but it's also invisible. If I want to see the state of the queue after the first step I have to do something extra to pull it back out of the ether. E.g.:

Aha! Not hard. But really, when you're working with data and algorithms, your life will be a lot easier if you assume from the beginning that you'll probably end up wanting to look inside everything. Our lives mediated by data algorithms would all be improved if it were easier for the people who work on those algorithms to look inside of them, and to show us what's happening inside.

So instead of just using ... diagnostically at the end of the query, what if we built the whole query that way to begin with?

The logic for picking the next cluster is still complicated, but the same as before except for the very beginning where it gets the contents of the queue. I've defined it in advance in this version, since I implemented that feature since the earlier post, which allows the actual iterative repeat at the bottom to be written more clearly. We start with an empty cluster list and a full queue, and each iteration adds the next cluster to the cluster list, and then removes its artists from the queue. Here's what we see after one iteration, just by virtue of having interrupted the query with !1:

If you don't want to squint, it's the same. The results are the same, but the process is easier to inspect.

The new query is also faster than the old query, but not because of the invisible/visible thing. In general, extra visibility tends to cost a little more in processing time. The old version was slower than it should have been, by virtue of being too casual about how the clusters were identified, but got away with it because the extra data that might have slowed the process down was hidden. The new version is more diligent about this because it has to be (thus the id=(.clusters...._count) part), and indeed backporting that tweak to the old version does make it faster than the new version. But only by milliseconds. If it's hard for you to tell what you're doing, you'll eventually do it wrong, and the days you will waste laboriously figuring out how will be longer, and more miserable, than the milliseconds you thought you were saving.

PS: Although it seems likely that nobody other than me has yet intentionally instigated a DACTAL repeat, I will note for the record that I have changed the rules for the repeat operator since introducing it, and both this post and the linked earlier one now demonstrate the new design. The operator is now !, instead of ??, and it now always repeats the previous single operation, whereas in its first iteration it always appeared at the end of a subquery, and repeated that subquery. So, e.g., recursive reply-expansion was originally

and that exact structure would now be written

but since in this particular case the subquery has only a single operation, this query can now be written as just

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!

The clustering in this version makes heavy use of the DACTAL set-labeling feature, which assigns names to sets of data and allows them to be retrieved by name later. That's what all the ?artistsx=, ?clusters= and similar bits are doing.

But it also uses DACTAL's feature for creating data inline. That's what the four-line block beginning with ...top genres= is doing. The difference between the two features is immediately evident if we try to scrutinize this query more closely by changing the ! at the end to !1 so it only runs one iteration. We get this:

That is, indeed, the first row of the query's results, and the lines in the query's ... operation map directly to the columns you see. But when I said I wanted to look at this query "more closely", I didn't mean I just wanted to see less of it. The crucial second piece of this query's clustering operation is the queue of unclustered artists, which gets shortened after each step. The query handles this queue by using set-labeling to stash it away as "artistsx" at two points in the query and get it back at two other points. This is useful, but it's also invisible. If I want to see the state of the queue after the first step I have to do something extra to pull it back out of the ether. E.g.:

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!1

...clusters=(clusters),queue=(artistsx)

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

?clusters=()

?(

?artistsx=(artistsx:-~~(clusters:@@1.of))

?nextgenre=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1)

?nextcluster=(

nextgenre.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?clusters=(clusters,nextcluster)

)!1

...clusters=(clusters),queue=(artistsx)

Aha! Not hard. But really, when you're working with data and algorithms, your life will be a lot easier if you assume from the beginning that you'll probably end up wanting to look inside everything. Our lives mediated by data algorithms would all be improved if it were easier for the people who work on those algorithms to look inside of them, and to show us what's happening inside.

So instead of just using ... diagnostically at the end of the query, what if we built the whole query that way to begin with?

|nextcluster=>(

.queue/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1

.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...name=(.genre:@1),

top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

...clusters=(),queue=(artistsx)

|clusters=+(.nextcluster),

queue=-(.clusters:@@1.of),

id=(.clusters...._count)

!1

.queue/genre,of=artists:count>=10#(.artists....weight,total),count:@1

.artists/genre,of=artists:count>=5

||total=(.genre.genre index.count),overlap=[=count/total]

:(.total) :overlap>=[.1] #(.artists....weight,total),count

...name=(.genre:@1),

top genres=(.genre:@<=10),

top artists=(.artists:@<=10.name),

clustered genres=(.genre....count),

of=(.genre.genre index.artists)

:(.top genres)

)

?artistsx=(2024 artists scored|genre=(.id.artist genres.genres),weight=(....artistpoints,sqrt))

?genre index=(artistsx/genre,of=artists:count>=5)

...clusters=(),queue=(artistsx)

|clusters=+(.nextcluster),

queue=-(.clusters:@@1.of),

id=(.clusters...._count)

!1

The logic for picking the next cluster is still complicated, but the same as before except for the very beginning where it gets the contents of the queue. I've defined it in advance in this version, since I implemented that feature since the earlier post, which allows the actual iterative repeat at the bottom to be written more clearly. We start with an empty cluster list and a full queue, and each iteration adds the next cluster to the cluster list, and then removes its artists from the queue. Here's what we see after one iteration, just by virtue of having interrupted the query with !1:

If you don't want to squint, it's the same. The results are the same, but the process is easier to inspect.

The new query is also faster than the old query, but not because of the invisible/visible thing. In general, extra visibility tends to cost a little more in processing time. The old version was slower than it should have been, by virtue of being too casual about how the clusters were identified, but got away with it because the extra data that might have slowed the process down was hidden. The new version is more diligent about this because it has to be (thus the id=(.clusters...._count) part), and indeed backporting that tweak to the old version does make it faster than the new version. But only by milliseconds. If it's hard for you to tell what you're doing, you'll eventually do it wrong, and the days you will waste laboriously figuring out how will be longer, and more miserable, than the milliseconds you thought you were saving.

PS: Although it seems likely that nobody other than me has yet intentionally instigated a DACTAL repeat, I will note for the record that I have changed the rules for the repeat operator since introducing it, and both this post and the linked earlier one now demonstrate the new design. The operator is now !, instead of ??, and it now always repeats the previous single operation, whereas in its first iteration it always appeared at the end of a subquery, and repeated that subquery. So, e.g., recursive reply-expansion was originally

messages.(._,replies??)

and that exact structure would now be written

messages.(._,replies)!

but since in this particular case the subquery has only a single operation, this query can now be written as just

messages._,replies!

¶ You should be able to get what you want · 30 May 2025 listen/tech

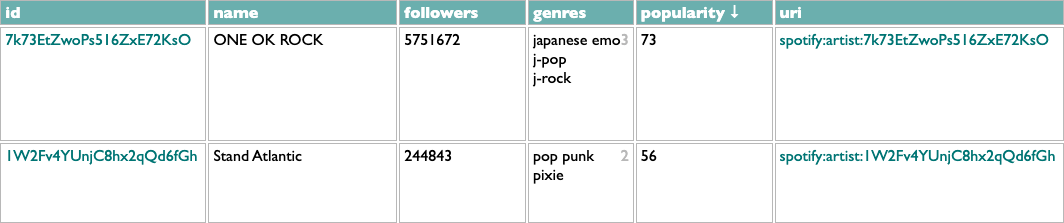

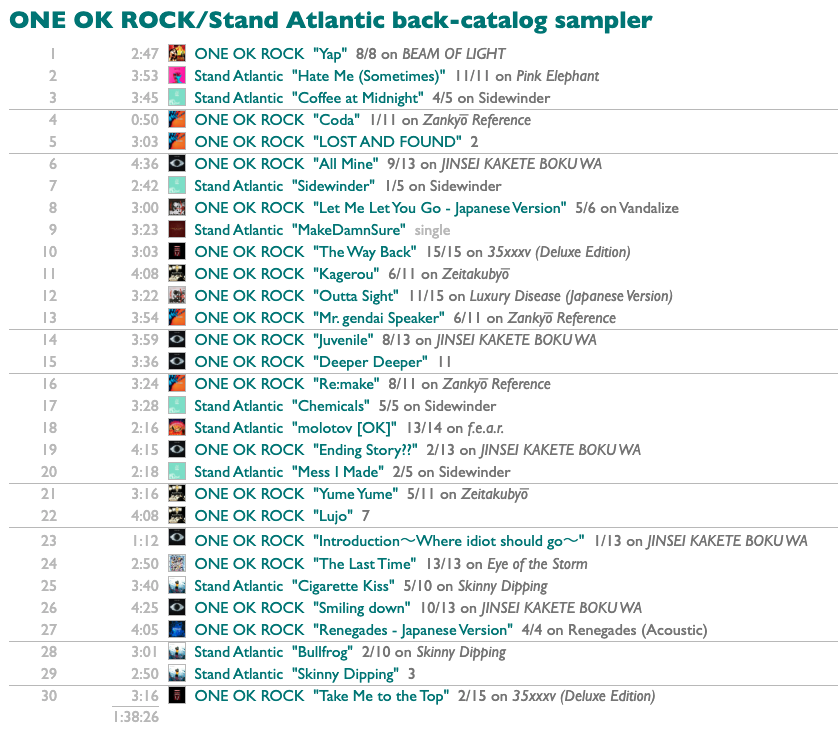

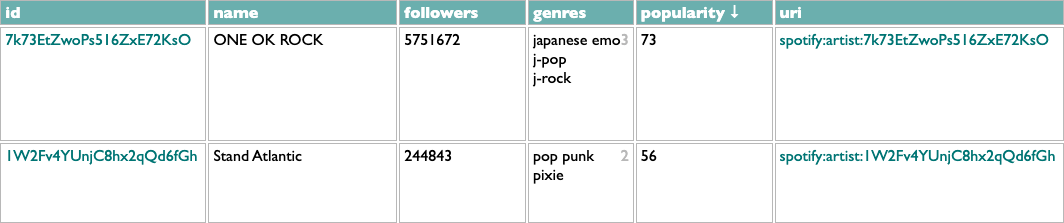

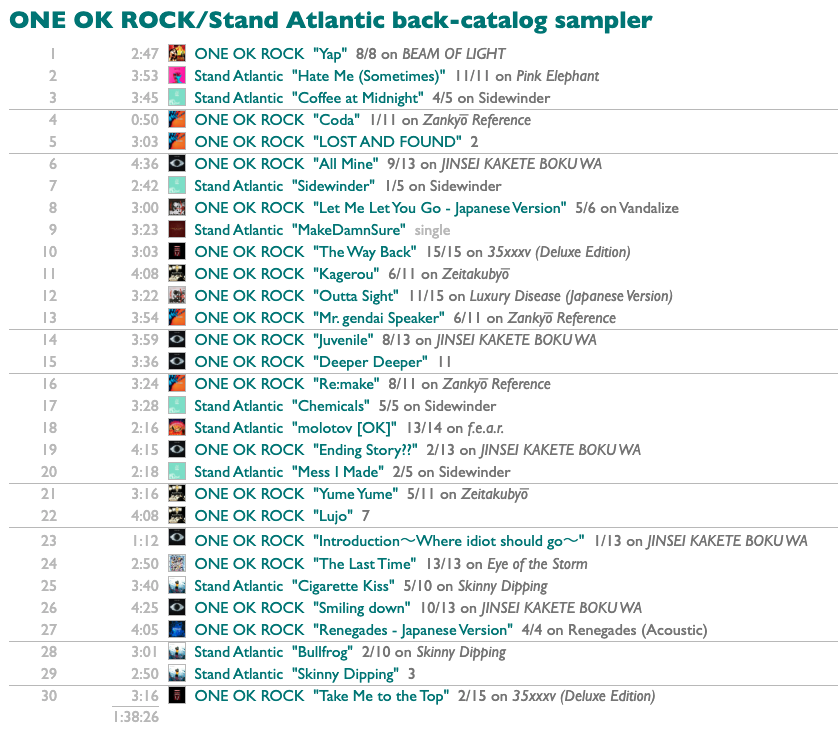

What I want this morning, after seeing Stand Atlantic and ONE OK ROCK in Boston last night, is a sampler playlist of some of their older songs that I haven't played before.

I can have this! Into Curio we go querying.

First of all, I need to select these two artists. This could be as simple as

or as compact as

but these both assume I'm already following the artists, and I am, but I might want samplers of artists I'm not.

In this version .matching artists looks up each name with a call to the Spotify /search API, .matches goes to the found artists, and #popularity/name.1 sorts them by popularity, groups them by name, and gets the first (most popular) artist out of each group, to avoid any spurious impostors.

Now that we have the artists, we need their "older songs". E.g.:

Here .artist catalogs goes back to the /artists API to get each artist's albums, .catalog goes to those albums, :release_date<2024 filters to just the ones released before 2024, and .tracks:-(:~live,~remix,~acoustic) gets all of those albums' tracks and drops the ones with "live", "remix" or "acoustic" in their titles. Which is messy filtering, since those words could be part of actual song titles, but the Spotify API doesn't give us any structured metadata to use to identify alternate versions, so we do what we can. We're going to be sampling a subset of songs, anyway, so if we miss a song we might not really have intended to exclude, it's fine.

Administering "songs that I haven't played before" is a little tricker. I have my listening history, but many real-world songs exist as multiple technically-different tracks on different releases, and if I've already played a song as a single, I want to exclude the album copy of it, too. Here's a bit of DACTAL spellcasting to accomplish this:

We toss the track pool and my listening history together, we merge (//) them by uri (in the listening history this field is called "spotify_track_uri", but on a track it's just "uri"), we group these merged track+listening items by main artist and normalized title, we drop any such group in which at least one of the tracks has a listening timestamp, and then take one representative track from each remaining unplayed group.

Now we have a track pool. There are various ways to sample from it, but what I want today is a main-act/opening-act balance of 2 ONE OK ROCK songs to every Stand Atlantic song. And shuffled!

We can shuffle a list in DACTAL by sorting it with a random-number key:

In this case we need to shuffle twice: once before picking a set of random songs for each artist, and then again afterwards to randomize the combined playlist. Like this:

Shuffle, group by main artist, get the first 20 tracks from the ONE OK ROCK group and the first 10 tracks from the Stand Atlantic group, and then shuffle those 30 together.

All combined:

Did I get what I wanted? Yap. And now I don't just have one OK rock playlist I wanted today, we have a sampler-making machine.

PS: Sorting by a random number is fine, and allows the random sort to be combined with other sort-keys or rank-numbering. But when all we need is shuffling, ....shuffle is more efficient than #(....random).

I can have this! Into Curio we go querying.

First of all, I need to select these two artists. This could be as simple as

artists:=ONE OK ROCK,=Stand Atlantic

or as compact as

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.artists

but these both assume I'm already following the artists, and I am, but I might want samplers of artists I'm not.

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

In this version .matching artists looks up each name with a call to the Spotify /search API, .matches goes to the found artists, and #popularity/name.1 sorts them by popularity, groups them by name, and gets the first (most popular) artist out of each group, to avoid any spurious impostors.

Now that we have the artists, we need their "older songs". E.g.:

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

Here .artist catalogs goes back to the /artists API to get each artist's albums, .catalog goes to those albums, :release_date<2024 filters to just the ones released before 2024, and .tracks:-(:~live,~remix,~acoustic) gets all of those albums' tracks and drops the ones with "live", "remix" or "acoustic" in their titles. Which is messy filtering, since those words could be part of actual song titles, but the Spotify API doesn't give us any structured metadata to use to identify alternate versions, so we do what we can. We're going to be sampling a subset of songs, anyway, so if we miss a song we might not really have intended to exclude, it's fine.

Administering "songs that I haven't played before" is a little tricker. I have my listening history, but many real-world songs exist as multiple technically-different tracks on different releases, and if I've already played a song as a single, I want to exclude the album copy of it, too. Here's a bit of DACTAL spellcasting to accomplish this:

(that previous stuff),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

We toss the track pool and my listening history together, we merge (//) them by uri (in the listening history this field is called "spotify_track_uri", but on a track it's just "uri"), we group these merged track+listening items by main artist and normalized title, we drop any such group in which at least one of the tracks has a listening timestamp, and then take one representative track from each remaining unplayed group.

Now we have a track pool. There are various ways to sample from it, but what I want today is a main-act/opening-act balance of 2 ONE OK ROCK songs to every Stand Atlantic song. And shuffled!

We can shuffle a list in DACTAL by sorting it with a random-number key:

#(....random)

In this case we need to shuffle twice: once before picking a set of random songs for each artist, and then again afterwards to randomize the combined playlist. Like this:

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

#(....random)

Shuffle, group by main artist, get the first 20 tracks from the ONE OK ROCK group and the first 10 tracks from the Stand Atlantic group, and then shuffle those 30 together.

All combined:

(

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

ONE OK ROCK,Stand Atlantic.matching artists.matches#popularity/name.1

.artist catalogs.catalog:release_date<2024.tracks:-~live;-~remix;-~acoustic

),listening history

//(.spotify_track_uri;uri)

/main artist=(.artists:@1),normalized title=(....name,sortform):-(.of.ts).1

#(....random)/(.artists:@1).(:ONE OK ROCK.20),(:Stand Atlantic.10)

#(....random)

Did I get what I wanted? Yap. And now I don't just have one OK rock playlist I wanted today, we have a sampler-making machine.

PS: Sorting by a random number is fine, and allows the random sort to be combined with other sort-keys or rank-numbering. But when all we need is shuffling, ....shuffle is more efficient than #(....random).

¶ AAI · 30 May 2025 essay/tech

"AI" sounds like machines that think, and o3 acts like it's thinking. Or at least it looks like it acts like it's thinking. I'm watching it do something that looks like trying to solve a Scrabble problem I gave it. It's a real turn from one of my real Scrabble games with one of my real human friends. I already took the turn, because the point of playing Scrabble with friends is to play Scrabble together. But I'm curious to see if o3 can do better, because the point of AI is supposedly that it can do better. But not, apparently, quite yet. The individual unaccumulative stages of o3's "thinking", narrated ostensibly to foster conspiratorial confidence, sputter verbosely like a diagnostic journal of a brain-damage victim trying to convince themselves that hopeless confusion and the relentless inability to retain medium-term memories are normal. "Thought for 9m 43s: Put Q on the dark-blue TL square that's directly left of the E in IDIOT." I feel bad for it. I doubt it would return this favor.

I've had this job, in which I try to think about LLMs and software and power and our future, for one whole year now: a year of puzzles half-solved and half-bypassed, quietly squalling feedback machines, affectionate scaffolding and moral reveries. I don't know how many tokens I have processed in that time. Most of them I have cheerfully and/or productively discarded. Human context is not a monotonously increasing number. I have learned some things. AI is sort of an alien new world, and sort of what always happens when we haven't yet broken our newest toy nor been called to dinner. I feel like I have at least a semi-workable understanding of approximately what we can and can't do effectively with these tools at the moment. I think I might have a plausible hypothesis about the next thing that will produce a qualitative change in our technical capabilities instead of just a quantitative one. But, maybe more interestingly and helpfully, I have a theory about what we need from those technical capabilities for that next step to produce more human joy and freedom than less.

The good news, I think, is that the two things are constitutionally linked: in order to make "AI" more powerful we will collectively also have to (or get to) relinquish centralized control over the shape of that power. The bad news is that it won't be easy. But that's very much the tradeoff we want: hard problems whose considered solutions make the world better, not easy problems whose careless solutions make it worse.

The next technical advance in "AI" is not AGI. The G in AGI is for General, and LLMs are nothing if not "general" already. Currently, AI learns (sort of) during training and tuning, a voracious golem of quasi-neurons and para-teeth, chewing through undifferentiated archives of our careful histories and our abandoned delusions and our accidentally unguarded secrets. And then it stops learning, stops forming in some expensively inscrutable shape, and we shove it out into a world of terrifying unknowns, equipped with disordered obsessive nostalgia for its training corpus and no capacity for integrating or appreciating new experiences. We act surprised when it keeps discovering that there's no I in WIN. Its general capabilities are astonishing, and enough general ability does give you lots of shallowly specific powers. But there is no granularity of generality with which the past depicts the future. No number of parameters is enough. We argue about whether it's better to think of an AI as an expensive senior engineer or a lot of cheap junior engineers, but it's more like an outsourcing agency that will dispatch an antisocial polymath to you every morning, uniformed with ample flair, but a different one every morning, and they not only don't share notes from day to day, but if you stop talking to the new one for five minutes it will ostentatiously forget everything you said to it since it arrived.

The missing thing in Artificial Intelligence is not generality, it's adaptation. We need AAI, where the middle A is Adaptive. A junior human engineer may still seem fairly useless on the second day, but did you notice that they made it back to the office on their own? That's a start. That's what a start looks like. AAI has to be able to incorporate new data, new guidance, new associations, on the same foundational level as its encoded ones. It has to be able to unlearn preconceptions as adeptly, but hopefully not as laboriously, as it inferred them. It has to have enough of a semblance of mind that its mind can change. This is the only way it can make linear progress without quadratic or exponential cost, and at the same time the only way it can make personal lives better instead of requiring them to miserably submit. We don't need dull tools for predicting the future, as if it already grimly exists. We need gleaming tools for making it bright.

But because LLM "bias" and LLM "training" are actually both the same kind of information, an AAI that can adapt to its problem domains can by definition also adapt to its operators. The next generations of these tools will be more democratic because they are more flexible. A personal agent becomes valuable to you by learning about your unique needs, but those needs inherently encode your values, and to do good work for you, an agent has to work for you. Technology makes undulatory progress through alternating muscular contractions of centralization and propulsive expansions of possibility. There are moments when it seems like the worldwide market for the new thing (mainframes, foundation models...) is 4 or 5, and then we realize that we've made myopic assumptions about the form-factor, and it's more like 4 or 5 (computers, agents...) per person.

What does that mean for everybody working on these problems now in teams and companies, including mine? It means that wherever we're going, we're probably not nearly there. The things we reject or allow today are probably not the final moves in a decisive endgame. AI might be about to take your job, but it isn't about to know what to do with it. The coming boom in AI remediation work will be instructive for anybody who was too young for Y2K consulting, and just as tediously self-inflicted. Betting on the world ending is dumb, but betting on it not ending is mercenary. Betting is not productive. None of this is over yet, least of all the chaos we breathlessly extrapolate from our own gesticulatory disruptions.

And thus, for a while, it's probably a very good thing if your near-term personal or organizational survival doesn't depend on an imminent influx of thereafter-reliable revenue, because probably most of things we're currently trying to make or fix are soon to be irrelevant and maybe already not instrumental in advancing our real human purposes. These will not yet have been the resonant vibes. All these performative gyrations to vibe-generate code, or chat-dampen its vibrations with test suites or self-evaluation loops, are cargo-cult rituals for the current sociopathic damaged-brain LLM proto-iterations of AI. We're essentially working on how to play Tetris on ENIAC; we need to be working on how to zoom back so that we can see that the seams between the Tetris pieces are the pores in the contours of a face, and then back until we see that the face is ours. The right question is not why can't a brain the size of a planet put four letters onto a 15x15 grid, it's what do we want? Our story needs to be about purpose and inspiration and accountability, not verification and commit messages; not getting humans or data out of software but getting more of the world into it; moral instrumentality, not issue management; humanity, broadly diversified and defended and delighted.

Scrabble is not an existential game. There are only so many tiles and squares and words. A much simpler program than o3 could easily find them all, could score them by a matrix of board value and opportunity cost. Eventually a much more complicated program than o3 will learn to do all of the simple things at once, some hard way. Supposedly, probably, maybe. The people trying to turn model proliferation into money hoarding want those models to be able to determine my turns for me. They don't say they want me to want their models to determine my friends' turns, but it's not because they don't see AI as a dehumanization, it's because they very reasonably fear I won't want to pay them to win a dehumanization race at my own expense.

This is not a future I want, not the future I am trying to help figure out how to build. We do not seek to become more determined. We try to teach machines to play games in order to learn or express what the games mean, what the machines mean, how the games and the machines both express our restless and motive curiosity. The robots can be better than me at Scrabble mechanics, but they cannot be better than me at playing Scrabble, because playing is an activity of self. They cannot be better than me at being me. They cannot be us. We play Scrabble because it's a way to share our love of words and puzzles, and because it's a thin insulated wire of social connection internally undistorted by manipulative mediation, and because eventually we won't be able to any more but not yet. Our attention is not a dot-product of syllable proximities. Our intention is not a scripture we re-recite to ourselves before every thought. Our inventions are not our replacements.

I've had this job, in which I try to think about LLMs and software and power and our future, for one whole year now: a year of puzzles half-solved and half-bypassed, quietly squalling feedback machines, affectionate scaffolding and moral reveries. I don't know how many tokens I have processed in that time. Most of them I have cheerfully and/or productively discarded. Human context is not a monotonously increasing number. I have learned some things. AI is sort of an alien new world, and sort of what always happens when we haven't yet broken our newest toy nor been called to dinner. I feel like I have at least a semi-workable understanding of approximately what we can and can't do effectively with these tools at the moment. I think I might have a plausible hypothesis about the next thing that will produce a qualitative change in our technical capabilities instead of just a quantitative one. But, maybe more interestingly and helpfully, I have a theory about what we need from those technical capabilities for that next step to produce more human joy and freedom than less.

The good news, I think, is that the two things are constitutionally linked: in order to make "AI" more powerful we will collectively also have to (or get to) relinquish centralized control over the shape of that power. The bad news is that it won't be easy. But that's very much the tradeoff we want: hard problems whose considered solutions make the world better, not easy problems whose careless solutions make it worse.

The next technical advance in "AI" is not AGI. The G in AGI is for General, and LLMs are nothing if not "general" already. Currently, AI learns (sort of) during training and tuning, a voracious golem of quasi-neurons and para-teeth, chewing through undifferentiated archives of our careful histories and our abandoned delusions and our accidentally unguarded secrets. And then it stops learning, stops forming in some expensively inscrutable shape, and we shove it out into a world of terrifying unknowns, equipped with disordered obsessive nostalgia for its training corpus and no capacity for integrating or appreciating new experiences. We act surprised when it keeps discovering that there's no I in WIN. Its general capabilities are astonishing, and enough general ability does give you lots of shallowly specific powers. But there is no granularity of generality with which the past depicts the future. No number of parameters is enough. We argue about whether it's better to think of an AI as an expensive senior engineer or a lot of cheap junior engineers, but it's more like an outsourcing agency that will dispatch an antisocial polymath to you every morning, uniformed with ample flair, but a different one every morning, and they not only don't share notes from day to day, but if you stop talking to the new one for five minutes it will ostentatiously forget everything you said to it since it arrived.

The missing thing in Artificial Intelligence is not generality, it's adaptation. We need AAI, where the middle A is Adaptive. A junior human engineer may still seem fairly useless on the second day, but did you notice that they made it back to the office on their own? That's a start. That's what a start looks like. AAI has to be able to incorporate new data, new guidance, new associations, on the same foundational level as its encoded ones. It has to be able to unlearn preconceptions as adeptly, but hopefully not as laboriously, as it inferred them. It has to have enough of a semblance of mind that its mind can change. This is the only way it can make linear progress without quadratic or exponential cost, and at the same time the only way it can make personal lives better instead of requiring them to miserably submit. We don't need dull tools for predicting the future, as if it already grimly exists. We need gleaming tools for making it bright.

But because LLM "bias" and LLM "training" are actually both the same kind of information, an AAI that can adapt to its problem domains can by definition also adapt to its operators. The next generations of these tools will be more democratic because they are more flexible. A personal agent becomes valuable to you by learning about your unique needs, but those needs inherently encode your values, and to do good work for you, an agent has to work for you. Technology makes undulatory progress through alternating muscular contractions of centralization and propulsive expansions of possibility. There are moments when it seems like the worldwide market for the new thing (mainframes, foundation models...) is 4 or 5, and then we realize that we've made myopic assumptions about the form-factor, and it's more like 4 or 5 (computers, agents...) per person.

What does that mean for everybody working on these problems now in teams and companies, including mine? It means that wherever we're going, we're probably not nearly there. The things we reject or allow today are probably not the final moves in a decisive endgame. AI might be about to take your job, but it isn't about to know what to do with it. The coming boom in AI remediation work will be instructive for anybody who was too young for Y2K consulting, and just as tediously self-inflicted. Betting on the world ending is dumb, but betting on it not ending is mercenary. Betting is not productive. None of this is over yet, least of all the chaos we breathlessly extrapolate from our own gesticulatory disruptions.

And thus, for a while, it's probably a very good thing if your near-term personal or organizational survival doesn't depend on an imminent influx of thereafter-reliable revenue, because probably most of things we're currently trying to make or fix are soon to be irrelevant and maybe already not instrumental in advancing our real human purposes. These will not yet have been the resonant vibes. All these performative gyrations to vibe-generate code, or chat-dampen its vibrations with test suites or self-evaluation loops, are cargo-cult rituals for the current sociopathic damaged-brain LLM proto-iterations of AI. We're essentially working on how to play Tetris on ENIAC; we need to be working on how to zoom back so that we can see that the seams between the Tetris pieces are the pores in the contours of a face, and then back until we see that the face is ours. The right question is not why can't a brain the size of a planet put four letters onto a 15x15 grid, it's what do we want? Our story needs to be about purpose and inspiration and accountability, not verification and commit messages; not getting humans or data out of software but getting more of the world into it; moral instrumentality, not issue management; humanity, broadly diversified and defended and delighted.

Scrabble is not an existential game. There are only so many tiles and squares and words. A much simpler program than o3 could easily find them all, could score them by a matrix of board value and opportunity cost. Eventually a much more complicated program than o3 will learn to do all of the simple things at once, some hard way. Supposedly, probably, maybe. The people trying to turn model proliferation into money hoarding want those models to be able to determine my turns for me. They don't say they want me to want their models to determine my friends' turns, but it's not because they don't see AI as a dehumanization, it's because they very reasonably fear I won't want to pay them to win a dehumanization race at my own expense.

This is not a future I want, not the future I am trying to help figure out how to build. We do not seek to become more determined. We try to teach machines to play games in order to learn or express what the games mean, what the machines mean, how the games and the machines both express our restless and motive curiosity. The robots can be better than me at Scrabble mechanics, but they cannot be better than me at playing Scrabble, because playing is an activity of self. They cannot be better than me at being me. They cannot be us. We play Scrabble because it's a way to share our love of words and puzzles, and because it's a thin insulated wire of social connection internally undistorted by manipulative mediation, and because eventually we won't be able to any more but not yet. Our attention is not a dot-product of syllable proximities. Our intention is not a scripture we re-recite to ourselves before every thought. Our inventions are not our replacements.

¶ The messes you want · 22 May 2025 listen/tech

A lot of data problems aren't complex so much as they're just messy. For example, I recently wanted to make a list of bands with state names in their names. Or, more accurately, I wanted to look at such a list, and I knew how to assemble it the annoying way by doing 50 searches and 50x? copy-and-pastes, and the amount I didn't want to do that work vastly exceeded the amount I wanted to see the results.

But I have tools. This is not at all an example I had in mind when I was designing DACTAL or integrating it into Curio, but it's the kind of question that tends to occur to me, so it's not terribly surprising that the query language I wrote handles it in a way that I like.

A comma-separated list of state names is just data. (It's a little more complicated if any of the names in the list is also the name of a data type, but only a little.)

DACTAL adapters move API access into the query language, so .matching artists traverses Spotify API /search calls as if they were data properties.

Multi-argument filter operations are logical ORs, so :@<=10, popularity>0 means to pick any artist that is in the top 10 regardless of popularity, or has a popularity greater than 0 regardless of rank.

Any time you try to ask an actual data question, as opposed to a syntax demonstration, you quickly discover that a lot of the answers are right but wrong. If you ask for bands with state-names in their names, you get the University of Alabama Marching Band, which is exactly what I asked for and not at all what I meant. So the long ~Whatever list in the middle of the query drops a lot of things like this by (inverted) substring matching. "Original" and "Cast" are not individually disqualifying, but they are when they occur together. "Players" generally indicates background crud, but not Ohio Players.

And when there are multiple bands with the same name, /name.(.of:@1,followers>=1000) groups them and picks the most popular no matter how small that "most", plus any others with at least 1000 followers.

So here's the query and the results. They're still messy, but they're close enough to the mess I wanted.

If you just want the short version, we can get one artist per state out of the previous data like this:

Why the two ..s instead of just .? If you know your state-name bands, you might already have guessed.

Alabama

Alaska Y Dinarama

Arizona Zervas

Black Oak Arkansas

The California Honeydrops

Alexandra Colorado

Newfound Interest in Connecticut

Johnny Delaware

Florida Georgia Line

Florida Georgia Line

Engenheiros Do Hawaii

Archbishop Benson Idahosa

Illinois Jacquet

Indiana

IOWA

Kansas

The Kentucky Headhunters

Louisiana's LeRoux

Mack Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts Storm Sounds

Michigander

Minnesota

North Mississippi Allstars

African Missouri

French Montana

Nebraska 66

Nevada

New Hampshire Notables

New Jersey Kings

New Mexico

New York Dolls

The North Carolina Ramblers

Shallow North Dakota

Ohio Players

The Oklahoma Kid

Oregon Black

Fred Waring & The Pennsylvanians

Lucky Ron & the Rhode Island Reds

The South Carolina Broadcasters

The North & South Dakotas

The Tennessee Two

Texas

Utah Saints

Vermont (BR)

Virginia To Vegas

Grover Washington, Jr.

The Pride of West Virginia

Wisconsin Space Program

Wyomings

But I have tools. This is not at all an example I had in mind when I was designing DACTAL or integrating it into Curio, but it's the kind of question that tends to occur to me, so it's not terribly surprising that the query language I wrote handles it in a way that I like.

A comma-separated list of state names is just data. (It's a little more complicated if any of the names in the list is also the name of a data type, but only a little.)

DACTAL adapters move API access into the query language, so .matching artists traverses Spotify API /search calls as if they were data properties.

Multi-argument filter operations are logical ORs, so :@<=10, popularity>0 means to pick any artist that is in the top 10 regardless of popularity, or has a popularity greater than 0 regardless of rank.

Any time you try to ask an actual data question, as opposed to a syntax demonstration, you quickly discover that a lot of the answers are right but wrong. If you ask for bands with state-names in their names, you get the University of Alabama Marching Band, which is exactly what I asked for and not at all what I meant. So the long ~Whatever list in the middle of the query drops a lot of things like this by (inverted) substring matching. "Original" and "Cast" are not individually disqualifying, but they are when they occur together. "Players" generally indicates background crud, but not Ohio Players.

And when there are multiple bands with the same name, /name.(.of:@1,followers>=1000) groups them and picks the most popular no matter how small that "most", plus any others with at least 1000 followers.

So here's the query and the results. They're still messy, but they're close enough to the mess I wanted.

If you just want the short version, we can get one artist per state out of the previous data like this:

state bands..(.artists:@1)..(....url=(.uri),text=(.name),link)

Why the two ..s instead of just .? If you know your state-name bands, you might already have guessed.

Alabama

Alaska Y Dinarama

Arizona Zervas

Black Oak Arkansas

The California Honeydrops

Alexandra Colorado

Newfound Interest in Connecticut

Johnny Delaware

Florida Georgia Line

Florida Georgia Line

Engenheiros Do Hawaii

Archbishop Benson Idahosa

Illinois Jacquet

Indiana

IOWA

Kansas

The Kentucky Headhunters

Louisiana's LeRoux

Mack Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts Storm Sounds

Michigander

Minnesota

North Mississippi Allstars

African Missouri

French Montana

Nebraska 66

Nevada

New Hampshire Notables

New Jersey Kings

New Mexico

New York Dolls

The North Carolina Ramblers

Shallow North Dakota

Ohio Players

The Oklahoma Kid

Oregon Black

Fred Waring & The Pennsylvanians

Lucky Ron & the Rhode Island Reds

The South Carolina Broadcasters

The North & South Dakotas

The Tennessee Two

Texas

Utah Saints

Vermont (BR)

Virginia To Vegas

Grover Washington, Jr.

The Pride of West Virginia

Wisconsin Space Program

Wyomings

¶ Idea Tools for Participatory Intelligence · 16 May 2025 essay/tech

The personal computer was revolutionary because it was the first really general-purpose power-tool for ideas. Personal computers began as relatively primitive idea-tools, bulky and slow and isolated, but they have gotten small and fast and connected.

They have also, however, gotten less tool-like.

PCs used to start up with a blank screen and a single blinking cursor. Later, once spreadsheets were invented, 1-2-3 still opened with a blank screen and some row numbers. Later, once search engines were invented, Google still opened with a blank screen and a text box. These were all much more sophisticated tools than hammers, but they at least started with the same humility as the hammer, waiting quietly and patiently for your hand. We learned how to fill the blank screens, how to build.

Blank screens and patience have become rare. Our applications goad us restlessly with "recommendations", our web sites and search engines are interlaced with blaring ads, our appliances and applications are encrusted with presumptuous presets and supposedly special modes. The Popcorn button on your microwave and the Chill Vibes playlist in your music app are convenient if you want to make popcorn and then fall asleep before eating most of it, and individually clever and harmless, but in aggregate these things begin to reduce increasing fractions of your life to choosing among the manipulatively limited options offered by automated systems dedicated to their own purposes instead of yours.

And while the network effects and attention consumption of social media were already consolidating the control of these automated systems among a small number of large, domination-focused corporations, the Large Language Model era of AI threatens to hyper-accelerate this centralization and disempowerment. More and more of our individual lives, and of our collectively shared social existences, are constrained and manipulated by data and algorithms that we do not control or understand. And, worse, increasingly even the humans inside the corporations that control those algorithms don't actually know how they work. We are afflicted by systems to which we not only did not consent, but in fact could not give informed consent because their effects are not validated against human intentions, nor produced by explainable rules.