25 July 2024 to 20 March 2024

¶ Corners of the world · 25 July 2024 listen/tech

I'm keeping a running list of book-related media links at the bottom of this post, but here are a few new things from an interestingly global week:

- I'm featured in an article about AI and the future in the French magazine Usbek & Rica this month. My copy hasn't arrvied yet, and I think it's in French, so I'm as curious as anybody what I said.

- Iveta Hajdakova and Tom Hoy at the London international consulting group Stripe Partners, who I know from some work they did for Spotify while I was there, interviewed me about algorithms and music for their Viewpoints series.

- There's an interview/feature with/about me and You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song both in print and online in the Polish magazine Polityka.

- I'll be making my second ever visit to the southern hemisphere, and first to New Zealand and Australia, to appear in conversation at Going Global Music Summit 2024 in Auckland, August 29-30, and then BIGSOUND 2024 in Brisbane, September 2-6!

- I'm featured in an article about AI and the future in the French magazine Usbek & Rica this month. My copy hasn't arrvied yet, and I think it's in French, so I'm as curious as anybody what I said.

- Iveta Hajdakova and Tom Hoy at the London international consulting group Stripe Partners, who I know from some work they did for Spotify while I was there, interviewed me about algorithms and music for their Viewpoints series.

- There's an interview/feature with/about me and You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song both in print and online in the Polish magazine Polityka.

- I'll be making my second ever visit to the southern hemisphere, and first to New Zealand and Australia, to appear in conversation at Going Global Music Summit 2024 in Auckland, August 29-30, and then BIGSOUND 2024 in Brisbane, September 2-6!

You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song began in a Google doc I had provisionally titled Every Noise at Once: New Fears and New Joys From the Streaming Liberation of All the World's Music. The first chapter-list I made there was mostly just a chronological free-association of stories I tell. That structure was useful in suggesting that there was probably a book's quantity of words involved, but when we started sending this outline and a few sample chapters to publishers, the fairly unanimous response was that I was not famous enough for strangers to want to read about my adventures in music just because I had them.

I couldn't really argue with that, nor did I actually want to write a memoir. I wanted to try to formulate an argument. Not an entirely straightforward or linear argument, exactly, but still, something more like an essay than a memoir: not every noise, and not at once, but particular noises, in an order with progressions and resolutions.

Restructuring the list of stories into the outline of an essay was easy and encouraging, and a couple of the chapters I had written already nearly fit the new structure, but the first version's first chapter was quite clearly the first chapter of a memoir, and I just deleted it and started over.

And by "deleted", I mean that I copied it into a different doc in case I thought of some other use for it later. I just came across that doc again, and blogs solve the not-famous-enough problem by not asking anybody but you to care whether you care. So here, for no other reason than that I wrote it once, is that original first chapter of the memoir I didn't write:

I couldn't really argue with that, nor did I actually want to write a memoir. I wanted to try to formulate an argument. Not an entirely straightforward or linear argument, exactly, but still, something more like an essay than a memoir: not every noise, and not at once, but particular noises, in an order with progressions and resolutions.

Restructuring the list of stories into the outline of an essay was easy and encouraging, and a couple of the chapters I had written already nearly fit the new structure, but the first version's first chapter was quite clearly the first chapter of a memoir, and I just deleted it and started over.

And by "deleted", I mean that I copied it into a different doc in case I thought of some other use for it later. I just came across that doc again, and blogs solve the not-famous-enough problem by not asking anybody but you to care whether you care. So here, for no other reason than that I wrote it once, is that original first chapter of the memoir I didn't write:

Chapter 1: Precious Jukeboxes

Without music, I would not even exist.

This is probably true in some existential or logistic way for a lot of people, but music is literally how my parents met. They were folk-singing in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1963. My mother had a duo with a friend. My father was in a Peter, Paul & Mary-esque trio. My father was my mother's guitar-teacher before either of them realized they were my parents.

After they got married they moved to Texas, where my father came from, and there I grew up, with their records and their acoustic guitars. We begin with our parents' music. In my case this was a stereo in a cabinet in our living room and a small collection of LPs, mostly folk standards like The Weavers and The Kingston Trio, and some of their 70s successors from the gentle margins of pop, like Joan Baez and Judy Collins and John Denver. My mother had some Ray Charles and Dave Brubeck records from when she wrote jazz reviews for her school paper, and Eddie Fisher records from her days in his Fan Club. They did buy new records, occasionally, but rarely by new artists. They loved and valued music, but without any sense of frantic urgency or gnawing incompleteness. And thus, if you'd tried to categorize recorded music as an economic activity based on their music spending, you would probably have put it in the same tier with handmade ceramics or gardening trowels.

For popular music, or really anything except my parents' records, there was the car radio. My parents were exactly the right demographic for NPR, but mercifully the wrong personality types for talk-radio, so from the back seat I got to hear Casey Kasem or whatever shuffled loop of the top 40 was playing during the week in between canonical countdowns.

Looking over the charts from my childhood years, I find that by the 1976 chart I recognize almost everything. That was the year I was given my first record-player of my own, and the store where my father bought it foisted two 7" singles on him as part of the deal, which he dutifully passed along to me, probably without having listened to them first: the Starland Vocal Band's frankly inappropriate "Afternoon Delight" and Walter Murphy's ridiculously discofied "A Fifth of Beethoven". I would happily listen to either of these songs again if for some reason I was once again imprisoned in a musical void where no other songs existed.

But my emergent taste wasn't much more adventurous than those. The first record I bought with my own money, which of course is a milestone that dates me by the fact that it's a milestone, was the Eagles' Hotel California. My record-budget was such that even a single LP was a serious investment subject to a ruthless risk-assessment that realistically required me to already have heard and loved at least four of its songs, and the only place I would have heard them was on the car radio. The viable size of the music industry, at least judged by its access to the record budget of an average American 10-year-old, was probably measured in dozens of artists.

One day, on that radio, I heard "Hold the Line", by Toto. Heard with any kind of perspective, Toto is the softest of soft-rock bands, and the maudlin, patronizing "Africa" has more fittingly become their limp sigil. But about 10 seconds into "Hold the Line" there's a power chord. It is not the first mainstream pop hit with a power chord, but somehow it was the first one I heard. It sounded like a difference engine, to me, or a dragon made out of moonlight, or some kind of god tearing the universe open along a revealed seam. The album cover has a sword. That sword sliced through my world.

I am fully aware that writing an origin-myth for a life-long obsession with heavy metal that begins with "Hold the Line" is like saying your love of Thai food began with a wide noodle dipped in Pop Rocks. But that's how it began, for me, and in my world in 1978, that's kind of the only way anything ever began. One sound can change your life. Toto led me towards Foreigner and Bad Company and Boston. Not via fast clicks, because there was no Fans Also Like to navigate through, but over the excruciating course of radio months and tentative spending. In 1979 I got my first radio, a flip-number clock radio with a single tiny speaker and no headphone jack, so I would turn the volume knob all the way down and then press my ear to it in order to listen to The Great American Radio Show after my supposed bedtime. I found the two Album Rock stations my parents never played in the car. Toto led me to Boston, which got me to Kansas and Supertramp, and then to Rush. Give 12-year-olds a radio of their own, and maybe you can have hundreds of artists instead of dozens.

Meanwhile, reading Michael Moorcock books got me to his lyric-writing for Hawkwind, and then Blue Öyster Cult, who were the first band I ever saw in concert. The Moorcock-co-written Blue Öyster Cult song "Veteran of the Psychic Wars" also appeared on the soundtrack for the 1981 movie Heavy Metal, and that soundtrack also had "The Mob Rules", by Black Sabbath.

I definitely hadn't heard that on the radio. "The Mob Rules" starts with that guitar noise from the very first moment, churning, relentless. Ronnie James Dio howls demonically, not like a halloween-costume devil but like an exiled lord of a forsaken realm. Cymbals start crashing like the night sky is the sun coming apart into shards. If pop was about melody, disco was about movement and rock was about energy, then metal was about power. Not about the ends of power or its victims, but about the visceral feeling of wielding it, of how it runs through you, of how it makes you want more.

Thus began my record-collecting life, in earnest, as a quest to find out what else the radio wasn't telling me about, and how else it could make me feel. But it was so hard to begin, when every step required all of your budget, and knowledge you mostly didn't have. Jukeboxes say 25¢ on them, which sounds cheap, but knowing what songs to play cost more than coins, and knowing what songs weren't in them didn't even have a coin slot. Music discovery, thus, was still barely a thing. Or it was, but as if Ferdinand Magellan had travelled from Portugal to Spain to receive a royal commission to go back and discover Portugal again.

And even if I had somehow discovered the shores of a new world, what would I have done? I'd heard "Dancing Queen", I knew ABBA were from Sweden, I knew roughly where that was. I didn't know it would later become a specifically important part of my life, but I'm sure I would have assumed there were more people making music there than just ABBA, if it had occurred to me to entertain the question.

But so what? There were no other Swedish pop songs on the radio. There were no other Swedish records in the record stores. There were no magazines about Swedish music at the drugstore, or books about it in the library. None of my friends knew anything else about Swedish music than ABBA, either. To learn about Gräs och Stenar, or Nationalteatern, or Gyllene Tider, all I would have been able to do was wait, patiently, to become old enough to get a job to save up for a plane ticket to Stockholm, where I would have had to find a telephone directory and figure out how to look up where the record stores were, and then go hope somebody in one of them spoke English and was willing to explain Swedish pop history to a random kid from Texas.

The world was full of music. But I was standing in the same record stores, flipping through the same few mute sealed packages over and over, wondering what was inside them and what was missing, wanting to know.

Without music, I would not even exist.

This is probably true in some existential or logistic way for a lot of people, but music is literally how my parents met. They were folk-singing in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1963. My mother had a duo with a friend. My father was in a Peter, Paul & Mary-esque trio. My father was my mother's guitar-teacher before either of them realized they were my parents.

After they got married they moved to Texas, where my father came from, and there I grew up, with their records and their acoustic guitars. We begin with our parents' music. In my case this was a stereo in a cabinet in our living room and a small collection of LPs, mostly folk standards like The Weavers and The Kingston Trio, and some of their 70s successors from the gentle margins of pop, like Joan Baez and Judy Collins and John Denver. My mother had some Ray Charles and Dave Brubeck records from when she wrote jazz reviews for her school paper, and Eddie Fisher records from her days in his Fan Club. They did buy new records, occasionally, but rarely by new artists. They loved and valued music, but without any sense of frantic urgency or gnawing incompleteness. And thus, if you'd tried to categorize recorded music as an economic activity based on their music spending, you would probably have put it in the same tier with handmade ceramics or gardening trowels.

For popular music, or really anything except my parents' records, there was the car radio. My parents were exactly the right demographic for NPR, but mercifully the wrong personality types for talk-radio, so from the back seat I got to hear Casey Kasem or whatever shuffled loop of the top 40 was playing during the week in between canonical countdowns.

Looking over the charts from my childhood years, I find that by the 1976 chart I recognize almost everything. That was the year I was given my first record-player of my own, and the store where my father bought it foisted two 7" singles on him as part of the deal, which he dutifully passed along to me, probably without having listened to them first: the Starland Vocal Band's frankly inappropriate "Afternoon Delight" and Walter Murphy's ridiculously discofied "A Fifth of Beethoven". I would happily listen to either of these songs again if for some reason I was once again imprisoned in a musical void where no other songs existed.

But my emergent taste wasn't much more adventurous than those. The first record I bought with my own money, which of course is a milestone that dates me by the fact that it's a milestone, was the Eagles' Hotel California. My record-budget was such that even a single LP was a serious investment subject to a ruthless risk-assessment that realistically required me to already have heard and loved at least four of its songs, and the only place I would have heard them was on the car radio. The viable size of the music industry, at least judged by its access to the record budget of an average American 10-year-old, was probably measured in dozens of artists.

One day, on that radio, I heard "Hold the Line", by Toto. Heard with any kind of perspective, Toto is the softest of soft-rock bands, and the maudlin, patronizing "Africa" has more fittingly become their limp sigil. But about 10 seconds into "Hold the Line" there's a power chord. It is not the first mainstream pop hit with a power chord, but somehow it was the first one I heard. It sounded like a difference engine, to me, or a dragon made out of moonlight, or some kind of god tearing the universe open along a revealed seam. The album cover has a sword. That sword sliced through my world.

I am fully aware that writing an origin-myth for a life-long obsession with heavy metal that begins with "Hold the Line" is like saying your love of Thai food began with a wide noodle dipped in Pop Rocks. But that's how it began, for me, and in my world in 1978, that's kind of the only way anything ever began. One sound can change your life. Toto led me towards Foreigner and Bad Company and Boston. Not via fast clicks, because there was no Fans Also Like to navigate through, but over the excruciating course of radio months and tentative spending. In 1979 I got my first radio, a flip-number clock radio with a single tiny speaker and no headphone jack, so I would turn the volume knob all the way down and then press my ear to it in order to listen to The Great American Radio Show after my supposed bedtime. I found the two Album Rock stations my parents never played in the car. Toto led me to Boston, which got me to Kansas and Supertramp, and then to Rush. Give 12-year-olds a radio of their own, and maybe you can have hundreds of artists instead of dozens.

Meanwhile, reading Michael Moorcock books got me to his lyric-writing for Hawkwind, and then Blue Öyster Cult, who were the first band I ever saw in concert. The Moorcock-co-written Blue Öyster Cult song "Veteran of the Psychic Wars" also appeared on the soundtrack for the 1981 movie Heavy Metal, and that soundtrack also had "The Mob Rules", by Black Sabbath.

I definitely hadn't heard that on the radio. "The Mob Rules" starts with that guitar noise from the very first moment, churning, relentless. Ronnie James Dio howls demonically, not like a halloween-costume devil but like an exiled lord of a forsaken realm. Cymbals start crashing like the night sky is the sun coming apart into shards. If pop was about melody, disco was about movement and rock was about energy, then metal was about power. Not about the ends of power or its victims, but about the visceral feeling of wielding it, of how it runs through you, of how it makes you want more.

Thus began my record-collecting life, in earnest, as a quest to find out what else the radio wasn't telling me about, and how else it could make me feel. But it was so hard to begin, when every step required all of your budget, and knowledge you mostly didn't have. Jukeboxes say 25¢ on them, which sounds cheap, but knowing what songs to play cost more than coins, and knowing what songs weren't in them didn't even have a coin slot. Music discovery, thus, was still barely a thing. Or it was, but as if Ferdinand Magellan had travelled from Portugal to Spain to receive a royal commission to go back and discover Portugal again.

And even if I had somehow discovered the shores of a new world, what would I have done? I'd heard "Dancing Queen", I knew ABBA were from Sweden, I knew roughly where that was. I didn't know it would later become a specifically important part of my life, but I'm sure I would have assumed there were more people making music there than just ABBA, if it had occurred to me to entertain the question.

But so what? There were no other Swedish pop songs on the radio. There were no other Swedish records in the record stores. There were no magazines about Swedish music at the drugstore, or books about it in the library. None of my friends knew anything else about Swedish music than ABBA, either. To learn about Gräs och Stenar, or Nationalteatern, or Gyllene Tider, all I would have been able to do was wait, patiently, to become old enough to get a job to save up for a plane ticket to Stockholm, where I would have had to find a telephone directory and figure out how to look up where the record stores were, and then go hope somebody in one of them spoke English and was willing to explain Swedish pop history to a random kid from Texas.

The world was full of music. But I was standing in the same record stores, flipping through the same few mute sealed packages over and over, wondering what was inside them and what was missing, wanting to know.

Large Language Models, by encoding our language, also encode our beliefs about ourselves, exactly as confused and conflicting as they seem to us when we read them, too. When we ask these models to answer questions, we would like to think we are invoking our most aggregated collective wisdom, but more realistically we are usually eliciting the mean of our conditioned beliefs. We talk to ChatGPT as if it has patiently and lovingly studied us, crystalizing all the latent truths we have half discovered and half suspected. But what we have actually constructed is an erratic analogical model, and the most interesting parts of it are probably the ones in the middle, which are also exactly the ones that LLMs as chatbots are least intent on revealing.

One of the many amazing things ChatGPT can do, though, is describe images in words. Another one of these amazing things it can do is produce images from descriptions.

It's entertaining to chain these two things together. Tell it to describe a picture in precise detail, then give it back that description and tell it to generate that image. Here's a picture of my wife and I eating a casually celebratory dinner:

And here's what image-to-description-to-image turns us into:

It made us younger and hotter, obviously, but the other details are also intriguing. All the drinks have limes, now, and straws pointing right. The one closed umbrella has been rendered canonically open and multiple. Every major detail in the original picture has been transliterated into its paradigmatic, normative form. This process is even more obvious if you keep going a few more iterations, feeding each generated image back into the loop:

We have converged on the LLM equivalent of Platonic Forms: the most soft-taco-like soft tacos, the most people-being-photographed haircuts, the most endlessly elemental green picnic benches. Somehow we've ended up with several of the definitive little metal containers of small-bite-accompanying sauces, even though the original picture had zero of these. If photography is the documentation of specific light that actually exists for an isolated instant, independent of our subjective and temporal experience of it, then this is the opposite of that: an illustration of the schemata through which we perceive. But in the case of images, instead of a mean schema that integrates all of our diverse models, we get a median one drawn carelessly from the somewhere in the middle: these anonymous pretty people and their tiny aiolis, not depicted so much as photorealistically caricatured by schematography.

But then, one of the interesting things about photography is that our experience of our environment is never a simple geometry of light. I have a favorite vantage point on the Longfellow Bridge, between Cambridge and Boston, where I stop and take another frame of the same slow movie almost every day. The view is singular. The river and the sky bracket it cinemascopically, with the Esplanade stretched out across the midline, and Beacon Hill and downtown Boston rising up ahead of the bridge. I like this image, too, but it absolutely does not capture the feeling of standing on the bridge.

Run this photograph through our schematograph converter, though, and you get something that is wildly inaccurate but also sort of closer to the feeling:

The resulting dreamscape is, like the couple and their soft tacos, surprisingly stable across further iterations:

The actual Boston city-planners could explain some hard-learned lessons about running elevated freeways through the middle of your city, and maybe also give some basic-engineering tips about how suspension works. But as a rendition of what our cities would look like in the future if we had learned nothing from the past, this is both shiny and apt.

For now, though, while the city is still less shiny and more walkable, walk across that bridge, down the ducklings' path and past The Embrace to the office with me. The office windows overlook Readers' Park and the Boston Irish Famine Memorial, across the street from the Old South Meeting House. This is an intersection richly invested with American history, and also a Chipotle.

Schematography quantizes the particular odd geometry of this plaza into something more generically recognizable as City.

The urban equivalent of tiny aiolis appears to be rooftop HVAC units, which the schematograph has introduced into the view on its own. It seems a bit confused about the nature of automobiles, and has placed a couple of them on rooftops, one on a sidewalk and another wedged sideways next to the crosswalk that goes nowhere. The bench placements are a little dubious, and somebody appears to have left a garbage can on top of one. There's no way in or out of the little park, which the man at about 10:30 in the image has just realized.

These weirdnesses mostly get normalized out with a few more iterations, other than the bad parking, which is arguably the most Boston-like feature that survives the schematography:

Sometimes schematography is kind of what we're trying to do with photography anyway. This is a picture I took at a concert, and if you weren't there and naturally don't care about which specific show I was at, the schematographs of using darkness and lights as a sensory proxy for loud music in a crowded room are about as effective as the original:

The drummer appears to be running out of drums by the last image, and is the guitarist going to play the thigh-high chinmes with the end of his guitar? Also, does the singer's uncle, dancing in the background, realize that he is visible to the audience?

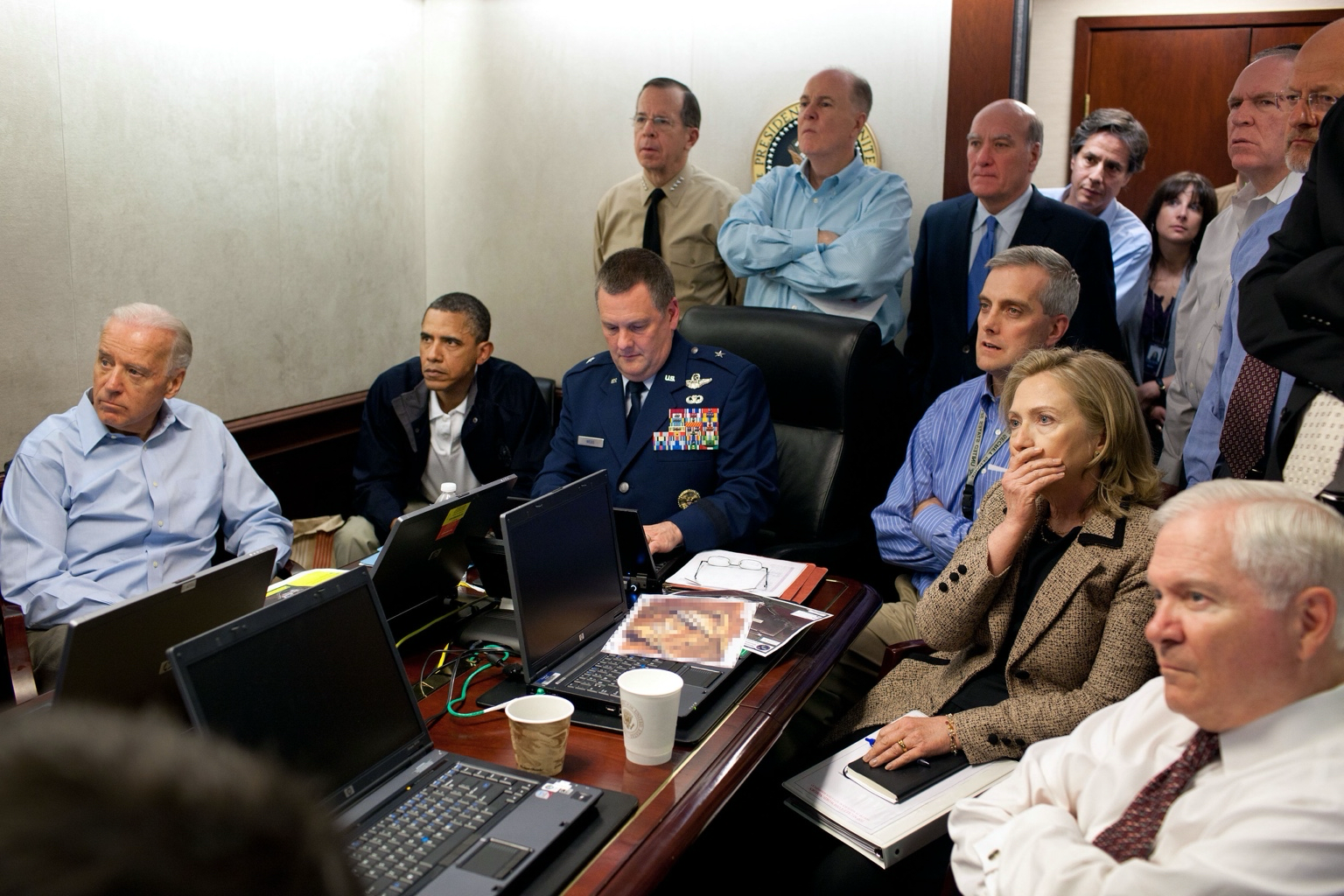

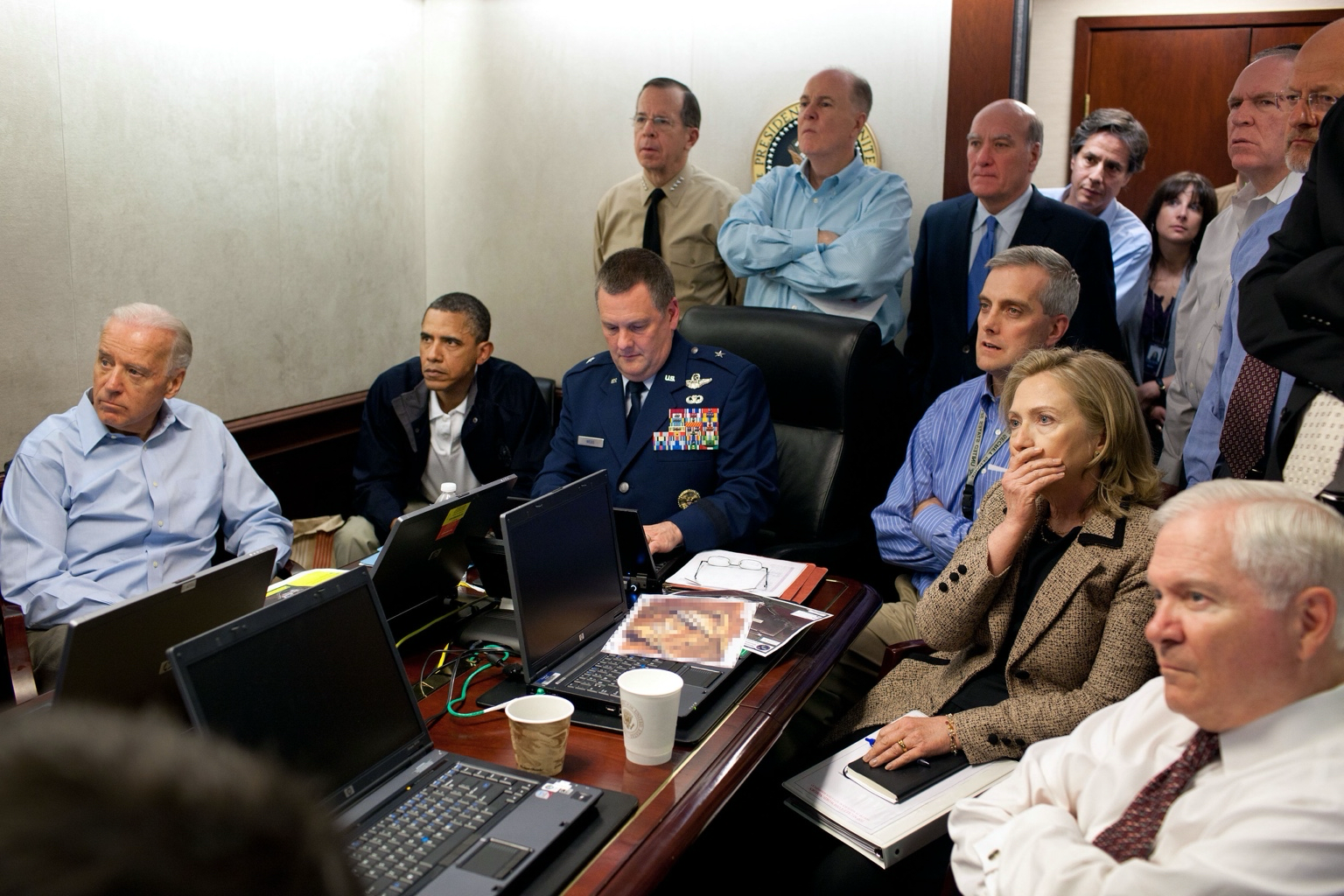

Sometimes, though, we take pictures to remember moments that specifically matter. Here's one of those:

Run reality through the schematograph and you can be reminded sharply about the difference between what actually happens and the assumptions that pile up in our data.

In the warroom of our unexamined dreams, the men are steely and pale, the cable-management is magical, and we have outgrown disposable coffee cups. Military men will clone themselves like minions if you aren't careful. You bring in just one to run the PowerPoint and by the time he has the screen-mirroring working correctly the room is full of them.

70 billion parameters are enough to suggest that some things are virtually certain. Men are serious, and serious things are meant for serious men. Serious men can be old or worried or both, but not neither. Serious men drink tap water. Women are occasional, but also the only ones who appear to be aware of what's going on around them. Something important is happening off-screen.

None of this is really news. Important things are always happening off-screen. Sometimes an unguarded reflection sneaks through, and we get a glimpse of the implied subject. The important present things for the future of Artificial Intelligence are probably the ways in which these schematographs and chatbots and accelerating generations are not intelligence, but the important present things for the future of people are probably the ways in which this automation is only superficially artificial. AI is not an alien oracle come to enlighten or enslave us. It's us, in increasingly elaborate costumes, aspiring to be unrecognizable in the most astonishing detail, but always absolutely unmistakable in our own limited and reconverging imaginations.

One of the many amazing things ChatGPT can do, though, is describe images in words. Another one of these amazing things it can do is produce images from descriptions.

It's entertaining to chain these two things together. Tell it to describe a picture in precise detail, then give it back that description and tell it to generate that image. Here's a picture of my wife and I eating a casually celebratory dinner:

And here's what image-to-description-to-image turns us into:

It made us younger and hotter, obviously, but the other details are also intriguing. All the drinks have limes, now, and straws pointing right. The one closed umbrella has been rendered canonically open and multiple. Every major detail in the original picture has been transliterated into its paradigmatic, normative form. This process is even more obvious if you keep going a few more iterations, feeding each generated image back into the loop:

We have converged on the LLM equivalent of Platonic Forms: the most soft-taco-like soft tacos, the most people-being-photographed haircuts, the most endlessly elemental green picnic benches. Somehow we've ended up with several of the definitive little metal containers of small-bite-accompanying sauces, even though the original picture had zero of these. If photography is the documentation of specific light that actually exists for an isolated instant, independent of our subjective and temporal experience of it, then this is the opposite of that: an illustration of the schemata through which we perceive. But in the case of images, instead of a mean schema that integrates all of our diverse models, we get a median one drawn carelessly from the somewhere in the middle: these anonymous pretty people and their tiny aiolis, not depicted so much as photorealistically caricatured by schematography.

But then, one of the interesting things about photography is that our experience of our environment is never a simple geometry of light. I have a favorite vantage point on the Longfellow Bridge, between Cambridge and Boston, where I stop and take another frame of the same slow movie almost every day. The view is singular. The river and the sky bracket it cinemascopically, with the Esplanade stretched out across the midline, and Beacon Hill and downtown Boston rising up ahead of the bridge. I like this image, too, but it absolutely does not capture the feeling of standing on the bridge.

Run this photograph through our schematograph converter, though, and you get something that is wildly inaccurate but also sort of closer to the feeling:

The resulting dreamscape is, like the couple and their soft tacos, surprisingly stable across further iterations:

The actual Boston city-planners could explain some hard-learned lessons about running elevated freeways through the middle of your city, and maybe also give some basic-engineering tips about how suspension works. But as a rendition of what our cities would look like in the future if we had learned nothing from the past, this is both shiny and apt.

For now, though, while the city is still less shiny and more walkable, walk across that bridge, down the ducklings' path and past The Embrace to the office with me. The office windows overlook Readers' Park and the Boston Irish Famine Memorial, across the street from the Old South Meeting House. This is an intersection richly invested with American history, and also a Chipotle.

Schematography quantizes the particular odd geometry of this plaza into something more generically recognizable as City.

The urban equivalent of tiny aiolis appears to be rooftop HVAC units, which the schematograph has introduced into the view on its own. It seems a bit confused about the nature of automobiles, and has placed a couple of them on rooftops, one on a sidewalk and another wedged sideways next to the crosswalk that goes nowhere. The bench placements are a little dubious, and somebody appears to have left a garbage can on top of one. There's no way in or out of the little park, which the man at about 10:30 in the image has just realized.

These weirdnesses mostly get normalized out with a few more iterations, other than the bad parking, which is arguably the most Boston-like feature that survives the schematography:

Sometimes schematography is kind of what we're trying to do with photography anyway. This is a picture I took at a concert, and if you weren't there and naturally don't care about which specific show I was at, the schematographs of using darkness and lights as a sensory proxy for loud music in a crowded room are about as effective as the original:

The drummer appears to be running out of drums by the last image, and is the guitarist going to play the thigh-high chinmes with the end of his guitar? Also, does the singer's uncle, dancing in the background, realize that he is visible to the audience?

Sometimes, though, we take pictures to remember moments that specifically matter. Here's one of those:

Run reality through the schematograph and you can be reminded sharply about the difference between what actually happens and the assumptions that pile up in our data.

In the warroom of our unexamined dreams, the men are steely and pale, the cable-management is magical, and we have outgrown disposable coffee cups. Military men will clone themselves like minions if you aren't careful. You bring in just one to run the PowerPoint and by the time he has the screen-mirroring working correctly the room is full of them.

70 billion parameters are enough to suggest that some things are virtually certain. Men are serious, and serious things are meant for serious men. Serious men can be old or worried or both, but not neither. Serious men drink tap water. Women are occasional, but also the only ones who appear to be aware of what's going on around them. Something important is happening off-screen.

None of this is really news. Important things are always happening off-screen. Sometimes an unguarded reflection sneaks through, and we get a glimpse of the implied subject. The important present things for the future of Artificial Intelligence are probably the ways in which these schematographs and chatbots and accelerating generations are not intelligence, but the important present things for the future of people are probably the ways in which this automation is only superficially artificial. AI is not an alien oracle come to enlighten or enslave us. It's us, in increasingly elaborate costumes, aspiring to be unrecognizable in the most astonishing detail, but always absolutely unmistakable in our own limited and reconverging imaginations.

¶ Filter domes, "made for you", and the kind of personalization that even makes personalization worse · 21 June 2024 listen/tech

Filter "bubbles" are charmingly weightless, delightful to pop. Sure, there's a slight soapy residue afterwards, but check your backpack: there are probably still a few old hand-sanitizer packets you shoved in there during the pandemic. Except sometimes you reach out, flirtatiously, to pop the shimmering bubble, and hit an intransigence made of polarized glass. Less bubble, more dome.

Spotify generates a lot of playlists that are "made for you", which generally means they have been aggressively adjusted to prioritize your previous listening. This is excellent for comfort, but terrible for exploration.

For example, Spotify is currently giving me a Synthwave Mix playlist on my Made For You page. I like synthwave, but I haven't been paying much focused attention to it lately, so it would be useful to me to hear what's going on there. "My" Synthwave Mix is made for me, though, so what it suggests is going on in synthwave is a) the handful of synthwave-adjacent bands I already specifically follow, and b) a lot of other bands I also already follow who are very definitely not synthwave.

I have a tool for this, though. If you stick the link to a Spotify made-for-you playlist into this:

https://everynoise.com/playlistprofile.cgi, e.g. Synthwave Mix

you can see what that playlist looks like before it gets personalized. In my case, this is almost completely different from what I end up with; only one artist* from the underlying source playlist ends up in my personalized version. That's not a lot of discovery potential. If there were a product feature to turn off the personalization, at least I could have discovered something here. Agency unlocks curiosity.

But since there are still, for the moment, better tools for genre exploration, I'm content to just ignore almost everything they make for me. In practice there is exactly one personalized Spotify playlist I use: Release Radar. This one is different because you actually do have some control over it, albeit not in a way that is totally apparent from looking at it. Release Radar will do its own inscrutable magic for you if you let it, but first it will find you new releases by artists you Follow. So if you follow enough artists, you can crowd out the "suggestions" and get a very useful release monitor. I follow 5124 artists, but you probably don't have to be that obsessive if you aren't me. Release Radar maxes out at 200 tracks. Even with 5124 artists to monitor, there are usually not more than 200 of them with new releases in any given week, so this is OK-ish. If you aren't me it's probably way more than enough.

In weeks when there are fewer than 200 new releases by artists I follow, Release Radar will fill out the rest of the 200 tracks with releases from the previous 3 weeks. This is an earnest idea, but counter-productive for me, personally, because I monitor new releases every week and I don't want to have the old tracks shown to me again as if they are new. So I generally stick my Release Radar playlist into the same playlist viewer linked above, where I can see the release dates of the tracks, and extract just the ones from the current week into a new playlist.

I usually do this first, and only really look at the new tracks once they're in the new playlist. This morning I went for a run before I'd done this, so I just put on Release Radar itself. The older tracks come at the end, and I wasn't going to be out for 12 hours, so it didn't matter. Later when I went to make my new-songs-only copy, though, I noticed that the first few tracks in my no-personalization viewer were not the same ones I had just heard. Weird. Flipping back and forth between the two views, it was clear that they were very different. Every Release Radar is unique, so my Release Radar is already filled with my artists, and thus you might think that this is the one time when "made for you" can't do any harm.

But oh, wait. Those older songs. Ugh.

Release Radar actually does assemble the list of new songs by artists I follow, like it's meant to. The pre-personalization view shows that this week 199 of my artists had new releases; only the 200th song in the underlying list is filler from a previous week. But then the made for you filter-dome snaps down, and songs I want to hear from this week are obtusely replaced with older songs by artists Spotify thinks are more familiar to me. Which are exactly the songs I am most likely to already have contemplated in the weeks when they were new. Two algorithms later, I end up with only 79 of the 199 new songs the first algorithm had in mind for me. "Catch all the latest music from artists you follow", Release Radar promises at the top. That's exactly what I want, and exactly what it could give me if it wanted to.

Algorithms, though, don't want things. We want things, and the algorithms do what they are ordered to do. I want all the latest music I might care about. Somebody who still works for Spotify wants something else. If you aren't me, maybe it still doesn't matter. If you only care about a few artists, you won't have this problem. If a streaming service only cares about people who only care about a few artists, they won't fix it**. If they don't employ enough people who care about everything, they may not even know. Maybe what they really want is to not have to care or know, and they have a comfort metric that allows them not to.

But all of this, the domes and the not caring and the not knowing, makes the world worse. I don't want to miss joy in favor of somebody else's obliviously generalized idea of my comfort. Neither should any of us.

* The one artist isn't even actually a synthwave artist. You can't really blame Spotify for that, though, as it's hardly their business to know the internal jargon of zero-cost content makers.

** One might reasonably ask why, given that I no longer work for Spotify, I haven't switched to some other streaming service, and the answer is that whatever they do or don't fix in the app, they still have the most useful programmatic API. That's how the playlist viewer works, and if you want new releases by all the artists you follow bad enough to write code, you can have that, too. And if you're me, now you do. One playlist minus one is zero. Ultimately the only person in "personalization" is the one doing it, and if you want your personalization to be personal, that person has to be you.

[23 August 2024 update: this week the post-processing reduces the underlying 200 songs in my Release Radar to just 30. That's pathetic.]

Spotify generates a lot of playlists that are "made for you", which generally means they have been aggressively adjusted to prioritize your previous listening. This is excellent for comfort, but terrible for exploration.

For example, Spotify is currently giving me a Synthwave Mix playlist on my Made For You page. I like synthwave, but I haven't been paying much focused attention to it lately, so it would be useful to me to hear what's going on there. "My" Synthwave Mix is made for me, though, so what it suggests is going on in synthwave is a) the handful of synthwave-adjacent bands I already specifically follow, and b) a lot of other bands I also already follow who are very definitely not synthwave.

I have a tool for this, though. If you stick the link to a Spotify made-for-you playlist into this:

https://everynoise.com/playlistprofile.cgi, e.g. Synthwave Mix

you can see what that playlist looks like before it gets personalized. In my case, this is almost completely different from what I end up with; only one artist* from the underlying source playlist ends up in my personalized version. That's not a lot of discovery potential. If there were a product feature to turn off the personalization, at least I could have discovered something here. Agency unlocks curiosity.

But since there are still, for the moment, better tools for genre exploration, I'm content to just ignore almost everything they make for me. In practice there is exactly one personalized Spotify playlist I use: Release Radar. This one is different because you actually do have some control over it, albeit not in a way that is totally apparent from looking at it. Release Radar will do its own inscrutable magic for you if you let it, but first it will find you new releases by artists you Follow. So if you follow enough artists, you can crowd out the "suggestions" and get a very useful release monitor. I follow 5124 artists, but you probably don't have to be that obsessive if you aren't me. Release Radar maxes out at 200 tracks. Even with 5124 artists to monitor, there are usually not more than 200 of them with new releases in any given week, so this is OK-ish. If you aren't me it's probably way more than enough.

In weeks when there are fewer than 200 new releases by artists I follow, Release Radar will fill out the rest of the 200 tracks with releases from the previous 3 weeks. This is an earnest idea, but counter-productive for me, personally, because I monitor new releases every week and I don't want to have the old tracks shown to me again as if they are new. So I generally stick my Release Radar playlist into the same playlist viewer linked above, where I can see the release dates of the tracks, and extract just the ones from the current week into a new playlist.

I usually do this first, and only really look at the new tracks once they're in the new playlist. This morning I went for a run before I'd done this, so I just put on Release Radar itself. The older tracks come at the end, and I wasn't going to be out for 12 hours, so it didn't matter. Later when I went to make my new-songs-only copy, though, I noticed that the first few tracks in my no-personalization viewer were not the same ones I had just heard. Weird. Flipping back and forth between the two views, it was clear that they were very different. Every Release Radar is unique, so my Release Radar is already filled with my artists, and thus you might think that this is the one time when "made for you" can't do any harm.

But oh, wait. Those older songs. Ugh.

Release Radar actually does assemble the list of new songs by artists I follow, like it's meant to. The pre-personalization view shows that this week 199 of my artists had new releases; only the 200th song in the underlying list is filler from a previous week. But then the made for you filter-dome snaps down, and songs I want to hear from this week are obtusely replaced with older songs by artists Spotify thinks are more familiar to me. Which are exactly the songs I am most likely to already have contemplated in the weeks when they were new. Two algorithms later, I end up with only 79 of the 199 new songs the first algorithm had in mind for me. "Catch all the latest music from artists you follow", Release Radar promises at the top. That's exactly what I want, and exactly what it could give me if it wanted to.

Algorithms, though, don't want things. We want things, and the algorithms do what they are ordered to do. I want all the latest music I might care about. Somebody who still works for Spotify wants something else. If you aren't me, maybe it still doesn't matter. If you only care about a few artists, you won't have this problem. If a streaming service only cares about people who only care about a few artists, they won't fix it**. If they don't employ enough people who care about everything, they may not even know. Maybe what they really want is to not have to care or know, and they have a comfort metric that allows them not to.

But all of this, the domes and the not caring and the not knowing, makes the world worse. I don't want to miss joy in favor of somebody else's obliviously generalized idea of my comfort. Neither should any of us.

* The one artist isn't even actually a synthwave artist. You can't really blame Spotify for that, though, as it's hardly their business to know the internal jargon of zero-cost content makers.

** One might reasonably ask why, given that I no longer work for Spotify, I haven't switched to some other streaming service, and the answer is that whatever they do or don't fix in the app, they still have the most useful programmatic API. That's how the playlist viewer works, and if you want new releases by all the artists you follow bad enough to write code, you can have that, too. And if you're me, now you do. One playlist minus one is zero. Ultimately the only person in "personalization" is the one doing it, and if you want your personalization to be personal, that person has to be you.

[23 August 2024 update: this week the post-processing reduces the underlying 200 songs in my Release Radar to just 30. That's pathetic.]

¶ You Have Not Yet Read Your Favourite Book · 20 June 2024 listen/tech

It's probably not the one I wrote. It would be weird if my book were your favorite book. It's a geeky book about music-streaming and music and algorithms and technology and curiosity and morality and where we are right now, and your favorite book should probably be an immortal novel about how we always are, or something you have re-read every year since you were 12 because it reminds you what you love and believe.

But my book about how streaming changes music is also kind of a book about loving and believing things, and the fears and joys that love and belief produce, because everything is if you really think about it, and I wrote a book about this stuff because I really think about it and didn't know how to stop.

As a method of not thinking about something any more, writing the book seems to have been fairly ineffective. I have kept thinking and writing about music and algorithms and technology and humanity. My new job, which doesn't have music anywhere in the wording of the mission, is just as fundamentally about figuring out how to use math and machines to amplify humanity instead of phase-cancelling it.

As an organized explanation of why I think streaming is good for music and music-streaming is good for humanity, though, I made it as coherent as I could. (And then a really good editor goaded me methodically into making it more coherent than that.) If you love music, you might like reading this book while you listen to whatever you are currently discovering or wondering or doubting. It's a book about discovery and wonder and productive doubt.

And it was officially published today.

You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song; Canbury Press, 2024.

US: bookshop.org or amazon.com or kindle

UK: uk.bookshop.org or amazon.co.uk or kindle UK

France (French): Hachette/Editions Marabout or Amazon.fr, September 2024

Taiwan (Chinese): ECUS Publishing House, December 2024

India (English): The Bombay Circle Press, December 2024

In London: Waterstones or Blackwells or Foyles

In Montreal: featured at Librairie Résonance

Some related links as I notice them:

2025

- One of Mixmag Asia's Six books on how streaming has forever changed our relationship with music, April 23

- A piece about the book in the Czech edition of Wired, February 4

2024

- A terrific review from book_click_deo on Instagram, December 23

- An interview for Fohlapress (or here) in Brazil, December 18

- An appearance on Bob Shami's Soundbreaker podcast, published December 12

- An interview in WNYU's STATIC magazine, December 7

- The Chinese and Indian editions are both out now, December 4

- The Chinese edition is coming! November 23

- Is this the 37th best book of 2024? An audacious claim from the Telegraph, November 17

- Read all the way to the end of this roundup of the best music books of 2024 in the Telegraph for a reminder that my book is optimistic and optimism is good, November 9

- The book and I feature in this Ars Technica story about a wave of junk music with real-artist names on Spotify, October 15

- An interview in the Chartmetric blog How Music Charts, October 9

- A review in The Quietus, September 28

- Carl Wilson and I talk about my book for the Popular Music Books in Process series, September 24

- A whole bonus episode of Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 30.

- An appearance on the NZ podcast The Fold, August 28

- A article based on an interview with Radio New Zealand in advance of appearing at Going Global, August 28

- A mention on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 19 (from about 7:40-10:20) teasing an upcoming special episode with me

- A (second) appearance on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 5 (from about 19:09-27:45)

- An interview/feature in the Polish magazine Polityka, July 27

- An interview with Tom and Iveta at Stripe Partners for their Viewpoints series, July 25

- A book citation as part of my introduction into a story about algorithms and music discovery in Mission magazine, July 17 (with the excellent pull-quote "If you don’t want algorithms to feed you passive listening, get active.")

- A conversation with Mark Richardson for the Third Bridge Creative blog, July 9

- A print rendition of the interview from the earlier German radio piece in Die Tageszeitung, July 4

- A conversation with Walt Hickey on the Numlock Sunday podcast, June 30

- An appearance on The Ray D'Arcy Show on RTE Radio 1 Ireland, June 25 (from about 26:10-50:37; clip)

- An interview in the Dutch newsletter Weekly Wav, June 25

- An appearance on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, June 24 (from about 7:00-18:00)

- A conversation on the podcast The Gist, June 20

- A short interview on Newstalk in Ireland, June 19 (with a Cactus World News shout!)

- A radio piece in German on Deutschlandfunk Kultur, June 19 (with blasts of gothic metal and wisps of theremin!)

- A "new book" mention on Tinnitist, June 16

- A review in the Telegraph, June 4; also available via Yahoo News

- A conversation with Chris Dalla Riva in his newsletter Can't Get Much Higher, May 26

- An earlier appearance on Ari Herstand's The New Music Business podcast, April 10, with some book-anticipation towards the end

- The book's page on Goodreads

But my book about how streaming changes music is also kind of a book about loving and believing things, and the fears and joys that love and belief produce, because everything is if you really think about it, and I wrote a book about this stuff because I really think about it and didn't know how to stop.

As a method of not thinking about something any more, writing the book seems to have been fairly ineffective. I have kept thinking and writing about music and algorithms and technology and humanity. My new job, which doesn't have music anywhere in the wording of the mission, is just as fundamentally about figuring out how to use math and machines to amplify humanity instead of phase-cancelling it.

As an organized explanation of why I think streaming is good for music and music-streaming is good for humanity, though, I made it as coherent as I could. (And then a really good editor goaded me methodically into making it more coherent than that.) If you love music, you might like reading this book while you listen to whatever you are currently discovering or wondering or doubting. It's a book about discovery and wonder and productive doubt.

And it was officially published today.

You Have Not Yet Heard Your Favourite Song; Canbury Press, 2024.

US: bookshop.org or amazon.com or kindle

UK: uk.bookshop.org or amazon.co.uk or kindle UK

France (French): Hachette/Editions Marabout or Amazon.fr, September 2024

Taiwan (Chinese): ECUS Publishing House, December 2024

India (English): The Bombay Circle Press, December 2024

In London: Waterstones or Blackwells or Foyles

In Montreal: featured at Librairie Résonance

Some related links as I notice them:

2025

- One of Mixmag Asia's Six books on how streaming has forever changed our relationship with music, April 23

- A piece about the book in the Czech edition of Wired, February 4

2024

- A terrific review from book_click_deo on Instagram, December 23

- An interview for Fohlapress (or here) in Brazil, December 18

- An appearance on Bob Shami's Soundbreaker podcast, published December 12

- An interview in WNYU's STATIC magazine, December 7

- The Chinese and Indian editions are both out now, December 4

- The Chinese edition is coming! November 23

- Is this the 37th best book of 2024? An audacious claim from the Telegraph, November 17

- Read all the way to the end of this roundup of the best music books of 2024 in the Telegraph for a reminder that my book is optimistic and optimism is good, November 9

- The book and I feature in this Ars Technica story about a wave of junk music with real-artist names on Spotify, October 15

- An interview in the Chartmetric blog How Music Charts, October 9

- A review in The Quietus, September 28

- Carl Wilson and I talk about my book for the Popular Music Books in Process series, September 24

- A whole bonus episode of Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 30.

- An appearance on the NZ podcast The Fold, August 28

- A article based on an interview with Radio New Zealand in advance of appearing at Going Global, August 28

- A mention on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 19 (from about 7:40-10:20) teasing an upcoming special episode with me

- A (second) appearance on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, August 5 (from about 19:09-27:45)

- An interview/feature in the Polish magazine Polityka, July 27

- An interview with Tom and Iveta at Stripe Partners for their Viewpoints series, July 25

- A book citation as part of my introduction into a story about algorithms and music discovery in Mission magazine, July 17 (with the excellent pull-quote "If you don’t want algorithms to feed you passive listening, get active.")

- A conversation with Mark Richardson for the Third Bridge Creative blog, July 9

- A print rendition of the interview from the earlier German radio piece in Die Tageszeitung, July 4

- A conversation with Walt Hickey on the Numlock Sunday podcast, June 30

- An appearance on The Ray D'Arcy Show on RTE Radio 1 Ireland, June 25 (from about 26:10-50:37; clip)

- An interview in the Dutch newsletter Weekly Wav, June 25

- An appearance on Your Morning Coffee Podcast, June 24 (from about 7:00-18:00)

- A conversation on the podcast The Gist, June 20

- A short interview on Newstalk in Ireland, June 19 (with a Cactus World News shout!)

- A radio piece in German on Deutschlandfunk Kultur, June 19 (with blasts of gothic metal and wisps of theremin!)

- A "new book" mention on Tinnitist, June 16

- A review in the Telegraph, June 4; also available via Yahoo News

- A conversation with Chris Dalla Riva in his newsletter Can't Get Much Higher, May 26

- An earlier appearance on Ari Herstand's The New Music Business podcast, April 10, with some book-anticipation towards the end

- The book's page on Goodreads

¶ Smoothies for Airports · 9 June 2024

My kid was that small once, too, so I know why this one sounds excited when she says "They have smoothies!" The world is full of strange things, and slowly you learn what some of them are, and that they are delightful. You learn to convert a world of unknowns into a world of delights, one pattern at a time.

And I was a parent of a kid that small once, too, so I know why this one, there in line at an airport banh mi stand at the beginning of what will almost certainly be a long day of strangenesses that resist conversion to delight, says "Oh. These are not normal smoothies. We can try to find you a normal smoothie somewhere else." The world is full of chaos. As a parent, in general but particularly in airports, you accept this in principle, but try to create a zone of exception around yourselves.

Except: here you are, in an airport, with a human who began with nothing and has progressed to delight at smoothies somehow, about to take them somewhere. We say things like this to children, our own children and our inner children, at our individual and collective peril. Our zones of exception tell ourselves stories of the world as other. We casually normalize some smoothies, and thus some people, some exceptions to the universal chaotic laws.

But the chaos is not other. We are not exceptions to the chaos, we are its most glorious children and works. We perturb it by throwing ourselves into it with all our powers: the power to integrate new tastes, the power to stay curious and open, the power to inpsire curiosity and openness. You had a tiny kid who had once never had anything that cold, and you made a kid who has learned to recognize smoothies on an airport menu as an opportunity for joy. You have given yourselves a choice, in this moment, between the order you both already know and a kid who discovers the sensation of boba popping out of the straw, a kid whose adventure begins every day before they even get on a plane, a kid who learns to say "What is that!" with italicized exclamation as they emerge into the world. This is why we have airports. This is why you left your house with her this morning. You have a choice, at every moment but particularly this one, between trying to stay as you are, or expand; between trying to pretend you circumscribe a predictable world with your arms and your enumerations of normal, or letting the world itself be the normal, and all of us become the ones together in its lovingly chaotic embrace.

And I was a parent of a kid that small once, too, so I know why this one, there in line at an airport banh mi stand at the beginning of what will almost certainly be a long day of strangenesses that resist conversion to delight, says "Oh. These are not normal smoothies. We can try to find you a normal smoothie somewhere else." The world is full of chaos. As a parent, in general but particularly in airports, you accept this in principle, but try to create a zone of exception around yourselves.

Except: here you are, in an airport, with a human who began with nothing and has progressed to delight at smoothies somehow, about to take them somewhere. We say things like this to children, our own children and our inner children, at our individual and collective peril. Our zones of exception tell ourselves stories of the world as other. We casually normalize some smoothies, and thus some people, some exceptions to the universal chaotic laws.

But the chaos is not other. We are not exceptions to the chaos, we are its most glorious children and works. We perturb it by throwing ourselves into it with all our powers: the power to integrate new tastes, the power to stay curious and open, the power to inpsire curiosity and openness. You had a tiny kid who had once never had anything that cold, and you made a kid who has learned to recognize smoothies on an airport menu as an opportunity for joy. You have given yourselves a choice, in this moment, between the order you both already know and a kid who discovers the sensation of boba popping out of the straw, a kid whose adventure begins every day before they even get on a plane, a kid who learns to say "What is that!" with italicized exclamation as they emerge into the world. This is why we have airports. This is why you left your house with her this morning. You have a choice, at every moment but particularly this one, between trying to stay as you are, or expand; between trying to pretend you circumscribe a predictable world with your arms and your enumerations of normal, or letting the world itself be the normal, and all of us become the ones together in its lovingly chaotic embrace.

¶ 10 aspirational rules for the moral operation of a music service · 4 June 2024 listen/tech

- The technical goal is to organize music so it is explorable. Exploration rewards curiosity.

- The product goal is to help listeners find joy. Joy is various.

- The feature goal is to connect individuals to communities. Music is a social energy.

- The business goal is to make money for artists. Not from.

- There should be one reward system, consistently applied. All financial contracts should be public.

- Listeners are entitled to their own data. Their stories, their love.

- Artists are entitled to their own data. Their audiences, their work.

- People are collectively entitled to their collective knowledge. Coherences, congruences.

- Musical taste and preference are emergent transiences of humans, yearned after by empathetic systems. Not imperious instruments of control.

- Never refer to music as “content”, even to yourself.

There is no chapter about generative AI in my book about music streaming. In part this is because while I was writing it, things were changing in AI so quickly that almost anything future-looking I tried to say would have been abjectly obsolete by the time the book was printed. But mostly it's because music's most pressing problems are cultural and economic, and do not require incomprehensibly complicated technical solutions. Spotify did a lot of machine learning for music recommendation purposes, and my rueful experience was that I could almost always do better, at least in the explainable human terms that I personally cared about, with SQL queries and math. I like math, but I hate SQL and once spent 4 years of my life trying to design a better query-language and data-model than that. I didn't pick tools because I liked them, I picked them because I cared about the results, and those were the tools that allowed me to produce results with human and cultural implications I could understand and attempt to improve.

All my jobs, I realize with the forced perspective of spending the last few months explaining my life to strangers over and over, have involved negotiating with machines on behalf of humanity. Algorithms and computer programs are tools for accomplishing human purposes. SQL JOINs and LLMs are ultimately both imperfect techniques for collecting collective knowledge, and like all tools should be held to the standard of allowing humans to be more human, more intentional, more curious, more joyful.

The music book is also a book about technology and algorithms and cultural mediation. In its first draft it had a very long and detailed chapter about the very many ways this technology can go wrong, which my editor cheerfully volunteered to preserve by moving it to an appendix. On reflection, I realized it actually belonged in a different book.

That book is provisionally called The Robots Will Not Win. The robots, at the moment, are not acting entirely convinced of this. My music streaming book is split about equally between new fears and new joys. As I started outlining the next one, it quickly became clear to me that I know more about the fears of AI than the joys. I don't want AI that pretends to be people. I don't want an internet clogged with mechanical recapitulations of word-correlations that humans have already established. I don't want luminous fictitious tiny houses in which you would have to climb over the sofa to get to a kitchen where the faucet pours water directly onto the countertop and the oven has no door. I don't want AI that turns human agency into vaguely prompted parades of anonymous golems.

And yet, I love people and I love computers. I love tools. Good tools imbue us with superpowers. We deserve good tools. Or, put the other way around, the more powerful our tools, the more urgent our obligations to make sure they are specifically built to empower humans, individually and collectively.

I didn't write this book intending it to be the end of a life-chapter, but when the interesting timing of my Spotify layoff presented the opportunity, it was surprisingly easy to change a few tenses and understand it as a cross between a progress report and an exit interview. There are plenty of things still to be done in music, but I'm going to try to help them with human advocacy and technological guidance for a while, instead of SQL queries embedded deeply in existing corporate constraints.

Meanwhile, it's not time to write the book I want to write about AI yet, because I don't know how it ends, or even necessarily how it goes next. But I know how it has to develop, because the tools change but we are still ourselves. I know what it feels like when good questions lead you to better questions instead of easier answers. I know that when we understand the fears better than the joys, the only thing to do is to make the joys we are missing.

Back to work.

All my jobs, I realize with the forced perspective of spending the last few months explaining my life to strangers over and over, have involved negotiating with machines on behalf of humanity. Algorithms and computer programs are tools for accomplishing human purposes. SQL JOINs and LLMs are ultimately both imperfect techniques for collecting collective knowledge, and like all tools should be held to the standard of allowing humans to be more human, more intentional, more curious, more joyful.

The music book is also a book about technology and algorithms and cultural mediation. In its first draft it had a very long and detailed chapter about the very many ways this technology can go wrong, which my editor cheerfully volunteered to preserve by moving it to an appendix. On reflection, I realized it actually belonged in a different book.

That book is provisionally called The Robots Will Not Win. The robots, at the moment, are not acting entirely convinced of this. My music streaming book is split about equally between new fears and new joys. As I started outlining the next one, it quickly became clear to me that I know more about the fears of AI than the joys. I don't want AI that pretends to be people. I don't want an internet clogged with mechanical recapitulations of word-correlations that humans have already established. I don't want luminous fictitious tiny houses in which you would have to climb over the sofa to get to a kitchen where the faucet pours water directly onto the countertop and the oven has no door. I don't want AI that turns human agency into vaguely prompted parades of anonymous golems.

And yet, I love people and I love computers. I love tools. Good tools imbue us with superpowers. We deserve good tools. Or, put the other way around, the more powerful our tools, the more urgent our obligations to make sure they are specifically built to empower humans, individually and collectively.

I didn't write this book intending it to be the end of a life-chapter, but when the interesting timing of my Spotify layoff presented the opportunity, it was surprisingly easy to change a few tenses and understand it as a cross between a progress report and an exit interview. There are plenty of things still to be done in music, but I'm going to try to help them with human advocacy and technological guidance for a while, instead of SQL queries embedded deeply in existing corporate constraints.

Meanwhile, it's not time to write the book I want to write about AI yet, because I don't know how it ends, or even necessarily how it goes next. But I know how it has to develop, because the tools change but we are still ourselves. I know what it feels like when good questions lead you to better questions instead of easier answers. I know that when we understand the fears better than the joys, the only thing to do is to make the joys we are missing.

Back to work.

¶ You Have Not Yet Pre-Ordered My Book · 5 May 2024

Or have you? If you haven't, and you want to, you can now do so in paper or screen form, on either side of one of the oceans. It comes out in June from Canbury Press.

US: bookshop.org or amazon.com or kindle

UK: uk.bookshop.org or amazon.co.uk or kindle UK

If it's news to you that I wrote a book, I announced it here. Some of the verb tenses have changed since then, but the future tense in which I have been talking about it is creeping steadily closer to present.

US: bookshop.org or amazon.com or kindle

UK: uk.bookshop.org or amazon.co.uk or kindle UK

If it's news to you that I wrote a book, I announced it here. Some of the verb tenses have changed since then, but the future tense in which I have been talking about it is creeping steadily closer to present.

¶ Music and Football · 20 March 2024 essay/listen

Spotify's Loud and Clear site includes an analogy between musicians and football players, ostensibly to explain how "aspirations" to make money from creative/athletic pursuits are more widespread than actual career success.

This comparison is not original or unique to Spotify, and does make some limited sense. With both art and sports, you can choose to spend your time on them, and the process of making music or training for football is labor in the sense of requiring time and effort, but most of the people making this choice are not going to end up being financially compensated for their labor. A small minority are able to make a living from it, but you cannot join this minority simply by wanting.

The key difference between music streaming and football, however, is that in music, every stadium is Wembley.

If you are an amateur soccer player, you know that you are an amateur soccer player. You play on an amateur team, in an amateur league, probably with amateur referees in a random city park that has other uses the rest of the week. No matter how astonishing a goal you score, it is a goal in an amateur game in a park on Sunday.

In music, however, everybody plays in the same venue, nominally in the same league. Any song on any of the major commercial music-streaming services could be streamed 1 billion times tomorrow. Structurally, in the music version of football, an amateur player from a local park could kick a ball and it could slip past Caoimhin Kelleher in the 121st minute to send Liverpool crashing out of the FA Cup.

That game was at Old Trafford, not Wembley, but the point is that this mostly doesn't happen. The statistical economic dynamics of music and football are very similar, which is why the analogy presented itself in the first place. But the aspirations are exactly why it doesn't work. In football, not only do you know your current status, but you can see the potential future steps in your career, and how they might happen. You could impress a local scout with your park goal, and get a tryout for a local semi-pro team. You could lead the semi-pro league in assists and get signed for a year by a second-division team. You could captain your second-division team to promotion, and like a fairy-tale, three years later you are getting crushed 7-0 by Manchester City and trying to claw your way out of the relegation zone so your dream can continue just a little bit longer.

In music, there used to be a story like this. You played club gigs in your hometown, and gave demo tapes to your friends. Somebody who ran a local label maybe heard you and liked you enough to help you put out a record. Maybe that record got played on college radio a little, and got you a chance at a deal on a minor major label. Maybe your minor major-label debut had a minor hit. Maybe your label stuck with you and you got to make more records. Maybe your third album has a song about getting drunk alone in your hometown and introducing yourself again to your friend's mother and it blows up and suddenly you are playing in Wembley. Or Fenway Park, at least.

Streaming offers the tantalizing illusion that these laborious steps have been eliminated by technology. But really they haven't. Music is an attention economy. The dominance of the biggest attention companies used to be reinforced by constraints of physical distribution, but it mostly survives the format shift. Most of the songs on the biggest playlists still come from the three major labels.

Which doesn't mean that the story of your potential career hasn't changed. The new steps might involve playlists instead of clubs, viral videos instead of college radio, and maybe a judicious distribution deal instead of an old-school contract with an advance you will never recoup. And these new steps, if they happen, could happen more suddenly than the old steps, and thus it can feel like they could happen suddenly at any moment.

But, still, mostly they won't. Mostly the paths to big success still go through labels, particularly major ones. Mostly the old major-attention economy survives through minor adaptations. Whatever aspirations they have, or labor they expend, most of the 10 million artists on streaming services will never get beyond semi-professional status in the most marginal sense of "semi". I have songs on Spotify, too. They took labor to make. A few people have streamed them, and I have been paid a few cents for those streams. Last time I checked, my lifetime earnings from streaming music were well on the way to $5. From $4.

But I am an amateur. I know I'm an amateur, I'm not trying to make a living by making music. If streaming services all start imposing minimum stream-thresholds for royalty payouts, I may never get to that glittering $5 in the distance, and that will be morally disappointing but practically fine.

If you're trying to become a professional, it's not fine. If regressive thresholds take away your sense of progress, that's not fine. If the successes you aspire towards operate like lotteries, so that you can't work towards them, that's not fine. If the people who operate the economy in which you will or will not be able to make a living sound like they are dismissing you as a non-participant, that's not fine.

I like the football analogy, actually, but I think it applies the other way around: if you own a stadium, and you invite all the players in the world to come in and play in front of all the fans, you don't have to promise them all glory, but you better not try to tell them that some of their goals won't count.

This comparison is not original or unique to Spotify, and does make some limited sense. With both art and sports, you can choose to spend your time on them, and the process of making music or training for football is labor in the sense of requiring time and effort, but most of the people making this choice are not going to end up being financially compensated for their labor. A small minority are able to make a living from it, but you cannot join this minority simply by wanting.

The key difference between music streaming and football, however, is that in music, every stadium is Wembley.

If you are an amateur soccer player, you know that you are an amateur soccer player. You play on an amateur team, in an amateur league, probably with amateur referees in a random city park that has other uses the rest of the week. No matter how astonishing a goal you score, it is a goal in an amateur game in a park on Sunday.

In music, however, everybody plays in the same venue, nominally in the same league. Any song on any of the major commercial music-streaming services could be streamed 1 billion times tomorrow. Structurally, in the music version of football, an amateur player from a local park could kick a ball and it could slip past Caoimhin Kelleher in the 121st minute to send Liverpool crashing out of the FA Cup.

That game was at Old Trafford, not Wembley, but the point is that this mostly doesn't happen. The statistical economic dynamics of music and football are very similar, which is why the analogy presented itself in the first place. But the aspirations are exactly why it doesn't work. In football, not only do you know your current status, but you can see the potential future steps in your career, and how they might happen. You could impress a local scout with your park goal, and get a tryout for a local semi-pro team. You could lead the semi-pro league in assists and get signed for a year by a second-division team. You could captain your second-division team to promotion, and like a fairy-tale, three years later you are getting crushed 7-0 by Manchester City and trying to claw your way out of the relegation zone so your dream can continue just a little bit longer.

In music, there used to be a story like this. You played club gigs in your hometown, and gave demo tapes to your friends. Somebody who ran a local label maybe heard you and liked you enough to help you put out a record. Maybe that record got played on college radio a little, and got you a chance at a deal on a minor major label. Maybe your minor major-label debut had a minor hit. Maybe your label stuck with you and you got to make more records. Maybe your third album has a song about getting drunk alone in your hometown and introducing yourself again to your friend's mother and it blows up and suddenly you are playing in Wembley. Or Fenway Park, at least.