4 December 2014 to 29 September 2014

¶ Metropopolis · 4 December 2014 listen/tech

Spotify just published the super-cool #YearInMusic thing, which shows a variety of statistical excerpts and summaries of both Spotify global listening and (if you're a Premium subscriber) your own for 2014.

Among other things, the global feature includes an editorial citation (which I had nothing to do with picking) for 2014's "Breakout Genre", Metropopolis.

You might not have heard of Metropopolis. A few people who also hadn't heard of it wrote indignant articles about this fact:

- Here Is Spotify's List of the Most Streamed Music of 2014, or What the Fuck Is Metropopolis? (from Noisey/Vice)

- Stop trying to make "metropopolis" happen: How Spotify forged a dubious new musical genre (from Salon)

Conversely, hundreds of people who hadn't heard of it either have now subscribed to the playlist that demonstrates what it means.

It doesn't actually much matter what it's called, I think. It's not a breakout genre name, it's a set of music that was breaking out in 2014. If you don't know what the name means, click the link and listen to it, and then you'll know. I don't care if it "happens", I care that you find more music you might love, and this might be some of it.

But it does also have a name, and I happen to know the story of how there came to be a thing with this name.

One of the things I watch over at work is the Echo Nest / Spotify list of genres. A genre can be any of many kinds of things, and can be varying degrees of known or unknown. In practical terms, "genre" for us kind of just means "thematic listening cluster", and our goal as we have expanded the list is to find and name and track as many such thematic listening clusters as we can identify in the world.

In most cases, these clusters exist in the world with a name. "Album rock" is a thing. "Samba" and "Nintendocore" and "Sega" are things (and Sega has nothing to do with Nintendocore!). We can model and track these, and make playlists to express them, but we don't have to name them.

But not all the clusters we find come with already-culturally-established names. What do you call the emerging cluster of loosely r&b-derived, often synthpop-orchestrated, generally sensual music that people like Frank Ocean and How to Dress Well are making? Various music-critics have suggested "pbr&b", "hipster r&b" and "r-neg-b", but most people who like the kind of music we're talking about don't know those terms. We originally named this cluster "r-neg-b", because of those three that was the one with the lowest amount of smug derision. But people kept accusing us of making that up, so we recently switched to calling it "indie r&b", on the theory that the music is kind of a cross between indie pop/rock/folk and r&b, and at least maybe you can guess what "indie r&b" might mean, whereas "r-neg-b" reads like a character-encoding error.

Or sometimes multiple clusters come with the same name. When you say "trap", for example, do you mean trap or trap? One is a hip-hop subgenre, the other is a largely-instrumental electronic subgenre. For our list, then, we have opted to eliminate the ambiguity by calling the hip-hop one "trap music" and the electronic one "trapstep". There's nothing magically right about those names, but they are at least different from each other.

And then, sometimes, because at Spotify we have maybe more data about human music-listening patterns than has ever existed before, we find clusters that you otherwise probably wouldn't be able to isolate, and thus wouldn't even have thought to name. For example, you know those rousing neo-rustic folk/pop-ish artists like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers that kind of sound like Dave Matthews ran over a jug band? We have the data to make a listening cluster around those with hundreds of other someway-similar bands. If you like that kind of music, you'll probably enjoy listening to this cluster. But it doesn't come with a name, exactly. So we called it "stomp and holler". We didn't totally make up that term, but it wasn't a genre name before we said so.

And you could argue that it still isn't a genre name, really, after we said so. This is fine. We don't have a philosophical or taxonomical agenda, we just have these clusters of awesome (usually) (to somebody) music, and we need some words to use as labels on a map, or as titles on playlists. When I have to make up names, I try to do so using the absolute minimum amount of creativity necessary to produce a unique new phrase, and thus we get a lot of rather mundane coinages like Malaysian pop and traditional reggae and atmospheric black metal. Sometimes I resolve name-ambiguity by the innovative linguistic wizardry of adding the words "more" or "deep", and thus we get a series of methodical techno clusters called deep house, deeper house and more deeper house. On the one hand, these are dopey names. On the other hand, if you like that kind of music, I'm betting that, in the same way that I continue to listen to BUMP OF CHICKEN, you'll still like listening to it long after you get over the name. (Or embrace it.)

Every once in a while, though, I lack the imagination to think of a boring name, and am thus forced to settle for a creative one. This is how the cluster of theatrical melodic metal with mostly operatic female vocals came to be called fallen angel. This is how the cluster of music that can sometimes sound like people singing distractedly while dissolving parchment sheet-music in beakers of gurgling solvent came to be called laboratorio. This is how the cluster of music that used to be New Wave only we're still listening to it now that it's old came to be called permanent wave. This is how we came to have shimmer pop and shiver pop and soul flow. I'd pick duller names if I could, but the names just exist to get you to the music.

The music, in all cases, is actually picked by computer programs using math to distill massive quantities of data. No matter what label I apply, these clusters exist because the world of people who make, listen to and write about music has collaboratively brought them into being by playing and listening and writing in particular combinations of patterns. In most cases, the computer programs use all this data to do two things: first they try to pick a set of cluster-appropriate artists, and then they try to pick those artists' most cluster-appropriate songs.

This often works, but not always. Take, for example, piano rock. The numbers we calculate to characterize songs don't identify individual instruments, so if you let the computers pick artists that fit the "piano rock" mold, you get a bunch of rock with pianos, but also a bunch of similar rock by bands that don't actually ever use pianos. We could have let this happen, and renamed the cluster "post-maudlin rock", but in the spirit of avoiding smug derision, we instead went through the artist-list by hand and made it deliver, at least roughly, on the promise of "piano rock".

And this is how we got metropopolis, too. I was listening, at one point, to a lot of indietronica, but when the computers made their indietronica playlist, I found that about half of it sounded like Chairlift and Chvrches to me, but half of it didn't. Which wasn't a problem, because "indietronica" doesn't have to sound like Chairlift and Chvrches, it just has to sound indie and tronic. But I wanted the cluster that did sound like Chairlift and Chvrches. So I made it. I had some other candidate names that I have since forgotten, but "metropopolis" seemed obviously better than the others as soon as it occurred to me, some kind of shiny aesthetic futurism with an insidious dystopian undertone.

I watch over this cluster myself. The computers are actually pretty good at suggesting potential additions, but I take the time to go through and listen to each one, and only put them into the cluster if they sound sufficiently metropopolistic. This is, from my point of view, an admission of temporary defeat. The computers ought to be able to do this by themselves. If we had a few more dimensions of audio analysis, quantifying just a few more psychoacoustic attributes, maybe we could isolate the precise buoyant glitteriness I hear, or the kind of resigned muting of energy that distinguishes some of the data candidates I reject. I don't, ultimately, think this cluster is any different from liquid funk or doo wop. It's a thing, I can hear it. The computers can't hear it yet. And I wanted to listen to it more than I wanted to wait for them to learn.

Among other things, the global feature includes an editorial citation (which I had nothing to do with picking) for 2014's "Breakout Genre", Metropopolis.

You might not have heard of Metropopolis. A few people who also hadn't heard of it wrote indignant articles about this fact:

- Here Is Spotify's List of the Most Streamed Music of 2014, or What the Fuck Is Metropopolis? (from Noisey/Vice)

- Stop trying to make "metropopolis" happen: How Spotify forged a dubious new musical genre (from Salon)

Conversely, hundreds of people who hadn't heard of it either have now subscribed to the playlist that demonstrates what it means.

It doesn't actually much matter what it's called, I think. It's not a breakout genre name, it's a set of music that was breaking out in 2014. If you don't know what the name means, click the link and listen to it, and then you'll know. I don't care if it "happens", I care that you find more music you might love, and this might be some of it.

But it does also have a name, and I happen to know the story of how there came to be a thing with this name.

One of the things I watch over at work is the Echo Nest / Spotify list of genres. A genre can be any of many kinds of things, and can be varying degrees of known or unknown. In practical terms, "genre" for us kind of just means "thematic listening cluster", and our goal as we have expanded the list is to find and name and track as many such thematic listening clusters as we can identify in the world.

In most cases, these clusters exist in the world with a name. "Album rock" is a thing. "Samba" and "Nintendocore" and "Sega" are things (and Sega has nothing to do with Nintendocore!). We can model and track these, and make playlists to express them, but we don't have to name them.

But not all the clusters we find come with already-culturally-established names. What do you call the emerging cluster of loosely r&b-derived, often synthpop-orchestrated, generally sensual music that people like Frank Ocean and How to Dress Well are making? Various music-critics have suggested "pbr&b", "hipster r&b" and "r-neg-b", but most people who like the kind of music we're talking about don't know those terms. We originally named this cluster "r-neg-b", because of those three that was the one with the lowest amount of smug derision. But people kept accusing us of making that up, so we recently switched to calling it "indie r&b", on the theory that the music is kind of a cross between indie pop/rock/folk and r&b, and at least maybe you can guess what "indie r&b" might mean, whereas "r-neg-b" reads like a character-encoding error.

Or sometimes multiple clusters come with the same name. When you say "trap", for example, do you mean trap or trap? One is a hip-hop subgenre, the other is a largely-instrumental electronic subgenre. For our list, then, we have opted to eliminate the ambiguity by calling the hip-hop one "trap music" and the electronic one "trapstep". There's nothing magically right about those names, but they are at least different from each other.

And then, sometimes, because at Spotify we have maybe more data about human music-listening patterns than has ever existed before, we find clusters that you otherwise probably wouldn't be able to isolate, and thus wouldn't even have thought to name. For example, you know those rousing neo-rustic folk/pop-ish artists like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers that kind of sound like Dave Matthews ran over a jug band? We have the data to make a listening cluster around those with hundreds of other someway-similar bands. If you like that kind of music, you'll probably enjoy listening to this cluster. But it doesn't come with a name, exactly. So we called it "stomp and holler". We didn't totally make up that term, but it wasn't a genre name before we said so.

And you could argue that it still isn't a genre name, really, after we said so. This is fine. We don't have a philosophical or taxonomical agenda, we just have these clusters of awesome (usually) (to somebody) music, and we need some words to use as labels on a map, or as titles on playlists. When I have to make up names, I try to do so using the absolute minimum amount of creativity necessary to produce a unique new phrase, and thus we get a lot of rather mundane coinages like Malaysian pop and traditional reggae and atmospheric black metal. Sometimes I resolve name-ambiguity by the innovative linguistic wizardry of adding the words "more" or "deep", and thus we get a series of methodical techno clusters called deep house, deeper house and more deeper house. On the one hand, these are dopey names. On the other hand, if you like that kind of music, I'm betting that, in the same way that I continue to listen to BUMP OF CHICKEN, you'll still like listening to it long after you get over the name. (Or embrace it.)

Every once in a while, though, I lack the imagination to think of a boring name, and am thus forced to settle for a creative one. This is how the cluster of theatrical melodic metal with mostly operatic female vocals came to be called fallen angel. This is how the cluster of music that can sometimes sound like people singing distractedly while dissolving parchment sheet-music in beakers of gurgling solvent came to be called laboratorio. This is how the cluster of music that used to be New Wave only we're still listening to it now that it's old came to be called permanent wave. This is how we came to have shimmer pop and shiver pop and soul flow. I'd pick duller names if I could, but the names just exist to get you to the music.

The music, in all cases, is actually picked by computer programs using math to distill massive quantities of data. No matter what label I apply, these clusters exist because the world of people who make, listen to and write about music has collaboratively brought them into being by playing and listening and writing in particular combinations of patterns. In most cases, the computer programs use all this data to do two things: first they try to pick a set of cluster-appropriate artists, and then they try to pick those artists' most cluster-appropriate songs.

This often works, but not always. Take, for example, piano rock. The numbers we calculate to characterize songs don't identify individual instruments, so if you let the computers pick artists that fit the "piano rock" mold, you get a bunch of rock with pianos, but also a bunch of similar rock by bands that don't actually ever use pianos. We could have let this happen, and renamed the cluster "post-maudlin rock", but in the spirit of avoiding smug derision, we instead went through the artist-list by hand and made it deliver, at least roughly, on the promise of "piano rock".

And this is how we got metropopolis, too. I was listening, at one point, to a lot of indietronica, but when the computers made their indietronica playlist, I found that about half of it sounded like Chairlift and Chvrches to me, but half of it didn't. Which wasn't a problem, because "indietronica" doesn't have to sound like Chairlift and Chvrches, it just has to sound indie and tronic. But I wanted the cluster that did sound like Chairlift and Chvrches. So I made it. I had some other candidate names that I have since forgotten, but "metropopolis" seemed obviously better than the others as soon as it occurred to me, some kind of shiny aesthetic futurism with an insidious dystopian undertone.

I watch over this cluster myself. The computers are actually pretty good at suggesting potential additions, but I take the time to go through and listen to each one, and only put them into the cluster if they sound sufficiently metropopolistic. This is, from my point of view, an admission of temporary defeat. The computers ought to be able to do this by themselves. If we had a few more dimensions of audio analysis, quantifying just a few more psychoacoustic attributes, maybe we could isolate the precise buoyant glitteriness I hear, or the kind of resigned muting of energy that distinguishes some of the data candidates I reject. I don't, ultimately, think this cluster is any different from liquid funk or doo wop. It's a thing, I can hear it. The computers can't hear it yet. And I wanted to listen to it more than I wanted to wait for them to learn.

¶ Every Noise at Xmas · 25 November 2014 listen/tech

To heroically understate the situation, I am not personally a fan of Christmas music.

But it's my job to help you enjoy the music you enjoy, not the music I enjoy. If you are one of the many, many people who enjoy Christmas music, this is your time of year, and to help you enjoy your time of year in the specific manner you enjoy most, the genre system I work on at Spotify actually has several subvariations of Christmas music:

Every Noise at Once - xmas genres

But according to our data, this is still just the surface of the seasonal alternate-reality. With a sufficiently jolly bias for inclusion and a merry tolerance of error we can find at least one maybe-genre-related maybe-xmas song for more than 1200 of our 1300+ genres. And, in fact, we can not only attempt to make xmas playlists for all genres, but we can then even rank the genres by how xmas-related they are, which is interesting information for both people who want to find xmas music and people who want to avoid it.

Every Noise at Once - all genres sorted by xmasness

But this sorting and filtering is all stuff I do normally, for my own purposes. If there is to be a non-denominational Xmas cleanly separable from the religious Christmas, it should probably revolve around the spirits of generosity and giving, which call for gestures that you don't merely do for yourself.

And so, in what I hope is this spirit, I have also made you this gift:

This is an algorithmically-generated xmas-specific manipulation of my genre map. It is the ultimate ornament, I think, a symbol-mosaic composited out of unsilent nights. I didn't draw the tree, I manipulated math so that the tree would self-organize that way. (Drawing it would have been faster.) Math doesn't believe or disbelieve, but it can multiply anybody's joy.

But it's my job to help you enjoy the music you enjoy, not the music I enjoy. If you are one of the many, many people who enjoy Christmas music, this is your time of year, and to help you enjoy your time of year in the specific manner you enjoy most, the genre system I work on at Spotify actually has several subvariations of Christmas music:

Every Noise at Once - xmas genres

But according to our data, this is still just the surface of the seasonal alternate-reality. With a sufficiently jolly bias for inclusion and a merry tolerance of error we can find at least one maybe-genre-related maybe-xmas song for more than 1200 of our 1300+ genres. And, in fact, we can not only attempt to make xmas playlists for all genres, but we can then even rank the genres by how xmas-related they are, which is interesting information for both people who want to find xmas music and people who want to avoid it.

Every Noise at Once - all genres sorted by xmasness

But this sorting and filtering is all stuff I do normally, for my own purposes. If there is to be a non-denominational Xmas cleanly separable from the religious Christmas, it should probably revolve around the spirits of generosity and giving, which call for gestures that you don't merely do for yourself.

And so, in what I hope is this spirit, I have also made you this gift:

This is an algorithmically-generated xmas-specific manipulation of my genre map. It is the ultimate ornament, I think, a symbol-mosaic composited out of unsilent nights. I didn't draw the tree, I manipulated math so that the tree would self-organize that way. (Drawing it would have been faster.) Math doesn't believe or disbelieve, but it can multiply anybody's joy.

I've been recording songs, however ineptly and infrequently, for a long time. Most of them have been on this site for hypothetical downloading (here). I don't sell them. If you take time out of your life to listen to them, that seems like a fair exchange to me.

They're now also on Spotify, so that you can not only listen to them, but even intermingle them with real music in playlists.

I've always just put my own name on them, but there are a bunch of people who share my name, and one of them already has an album that isn't mine on Spotify. So I've hereby and retroactively adopted the band-name Aedliga. This is pronounced "AID-li-guh", and has no meaning. It was also the name of one of my songs a few years ago, in which context it also meant nothing, but was the title track for that notional EP, so that there is now "Aedliga" by Aedliga on Aedliga. And there's aedliga.com and @aedliga, and furia.com/isthisbandnametaken now dutifully reports that the name is taken.

I'll let you know when the T-shirts are ready.

They're now also on Spotify, so that you can not only listen to them, but even intermingle them with real music in playlists.

I've always just put my own name on them, but there are a bunch of people who share my name, and one of them already has an album that isn't mine on Spotify. So I've hereby and retroactively adopted the band-name Aedliga. This is pronounced "AID-li-guh", and has no meaning. It was also the name of one of my songs a few years ago, in which context it also meant nothing, but was the title track for that notional EP, so that there is now "Aedliga" by Aedliga on Aedliga. And there's aedliga.com and @aedliga, and furia.com/isthisbandnametaken now dutifully reports that the name is taken.

I'll let you know when the T-shirts are ready.

¶ In Harper's · 27 October 2014 listen/tech

I make a very sidebarred appearance in the November 2014 Harper's Magazine Readings section (page 21), where they list some of the genres that amused them in my genre map. The choices seem a little random to me (why is "Yugoslav rock" funny?), and I can't explain why they felt "Viking" had to be capitalized, but it's cool to appear in a magazine I actually used to read.

¶ The Sounds of Cities · 23 October 2014 listen/tech

I had limited expectations for applying the logic from The Sounds of Places, which is based on whole countries, to individual cities. Cities are smaller than countries, and data-wise, smaller usually means more random.

And maybe there is more randomness, overall, but there's enough non-randomness to be intriguing. Or, to put this another way, any chance that I wouldn't publish this evaporated when The Sound of Dundee turned out to, in fact, include the immortal "The Unicorn Invasion of Dundee" by Gloryhammer.

The Sounds of US Cities

The Sounds of European Cities

And maybe there is more randomness, overall, but there's enough non-randomness to be intriguing. Or, to put this another way, any chance that I wouldn't publish this evaporated when The Sound of Dundee turned out to, in fact, include the immortal "The Unicorn Invasion of Dundee" by Gloryhammer.

The Sounds of US Cities

The Sounds of European Cities

¶ (Almost) No One Is Immune · 21 October 2014 listen/tech

At work I've been looking at the distinctive collective music listening of individual US cities. A lot of this, as you might imagine, turns out to be local music from in or near each city, or pop music with some sort of regional connection.

But statistically, the most popular "national" hits tend to get mixed in with the local stuff at some point, through sheer ubiquity. Taylor Swift's "Shake It Off" is the most obvious example of this at the moment, a song so popular that it's basically representative of the distinctive listening of humans, or at least of American humans who use Spotify.

For amusement, though, here is a ranking of major US Cities by where on their most-distinctive current song chart "Shake It Off" ranks as of today. The cities at the top are the ones who have surrendered most unreservedly to "Shake It Off", either through genuine disproportionate enthusiasm, and/or because they just don't have anything better of their own to play. The ones at the bottom have maintained the strongest resistance to this invasion. The >100s at the very bottom show the cities where immunity is so strong that "Shake It Off" doesn't even make the top 100 most-distinctive songs.

Presumably none of this will bother Taylor, but "people who are not going to listen disproportionately are going to not listen disproportionately" wouldn't fit the meter of the song very well, so I assume that's why she didn't mention it.

But statistically, the most popular "national" hits tend to get mixed in with the local stuff at some point, through sheer ubiquity. Taylor Swift's "Shake It Off" is the most obvious example of this at the moment, a song so popular that it's basically representative of the distinctive listening of humans, or at least of American humans who use Spotify.

For amusement, though, here is a ranking of major US Cities by where on their most-distinctive current song chart "Shake It Off" ranks as of today. The cities at the top are the ones who have surrendered most unreservedly to "Shake It Off", either through genuine disproportionate enthusiasm, and/or because they just don't have anything better of their own to play. The ones at the bottom have maintained the strongest resistance to this invasion. The >100s at the very bottom show the cities where immunity is so strong that "Shake It Off" doesn't even make the top 100 most-distinctive songs.

| # | City |

| 1 | Arlington VA |

| 1 | Chandler |

| 1 | Gilbert |

| 1 | Mesa |

| 2 | Akron |

| 2 | Albany |

| 2 | Anchorage |

| 2 | Cleveland |

| 2 | New Haven |

| 2 | Pasadena |

| 2 | Tucson |

| 2 | Worcester |

| 3 | Alexandria |

| 3 | Des Moines |

| 3 | Orange |

| 3 | Scottsdale |

| 3 | Vancouver |

| 3 | Wilmington DE |

| 4 | Hoboken |

| 4 | Plano |

| 4 | Pompano Beach |

| 5 | Gainesville |

| 5 | Hartford |

| 5 | Somerville |

| 5 | Syracuse |

| 5 | Tacoma |

| 5 | Wichita |

| 6 | Bellevue |

| 6 | Providence |

| 6 | Reno |

| 6 | State College |

| 7 | Colorado Springs |

| 7 | Santa Clara |

| 8 | Aurora |

| 8 | Little Rock |

| 9 | Littleton |

| 9 | Tempe |

| 10 | East Lansing |

| 10 | Tampa |

| 10 | Trenton |

| 10 | Virginia Beach |

| 11 | Irvine |

| 11 | Sunnyvale |

| 12 | Albuquerque |

| 12 | Chicago |

| 13 | Boise |

| 13 | Boston |

| 13 | Cambridge |

| 13 | Las Vegas |

| 13 | Philadelphia |

| 13 | Silver Spring |

| 13 | Spokane |

| 14 | Dayton |

| 14 | Jacksonville |

| 14 | Miami Beach |

| 14 | Overland Park |

| 15 | Durham |

| 15 | Eugene |

| 15 | Lexington |

| 15 | St. Louis |

| 16 | Raleigh |

| 16 | Washington DC |

| 17 | Boca Raton |

| 17 | Springfield MO |

| 18 | Greensboro |

| 18 | Greenville |

| 18 | Spring |

| 19 | Cincinnati |

| 19 | Hyattsville |

| 19 | Murfreesboro |

| 20 | Fremont |

| 20 | Fresno |

| 20 | Ithaca |

| 20 | Tallahassee |

| 21 | Bloomington |

| 21 | Indianapolis |

| 21 | Pittsburgh |

| 23 | Corona |

| 23 | Phoenix |

| 24 | Frisco |

| 25 | Columbia MO |

| 26 | Ann Arbor |

| 26 | Denton |

| 26 | San Luis Obispo |

| 26 | West Palm Beach |

| 27 | Grand Rapids |

| 27 | Madison |

| 27 | Norman |

| 28 | Norfolk |

| 29 | Jersey City |

| 29 | Orlando |

| 29 | San Jose |

| 30 | Lawrence |

| 30 | Louisville |

| 31 | Bakersfield |

| 31 | Omaha |

| 32 | New York |

| 32 | Richmond |

| 33 | Salt Lake City |

| 34 | Columbus |

| 34 | Lewisville |

| 34 | Oklahoma City |

| 35 | Milwaukee |

| 36 | Wilmington NC |

| 37 | Columbia SC |

| 37 | Santa Barbara |

| 38 | San Diego |

| 39 | Charleston |

| 40 | Lincoln |

| 40 | Toledo |

| 41 | Long Beach |

| 41 | Riverside |

| 41 | St. Paul |

| 42 | Urbana |

| 43 | Berkeley |

| 44 | Katy |

| 44 | Minneapolis |

| 45 | Buffalo |

| 46 | Stockton |

| 47 | El Paso |

| 49 | Fort Collins |

| 54 | Charlotte |

| 55 | Chapel Hill |

| 55 | Kansas City |

| 55 | Knoxville |

| 55 | Tulsa |

| 56 | New Orleans |

| 57 | Denver |

| 58 | Farmington |

| 60 | Concord |

| 60 | San Antonio |

| 64 | Baton Rouge |

| 67 | Birmingham |

| 68 | Hayward |

| 73 | Mountain View |

| 81 | Whittier |

| 83 | Seattle |

| 85 | Humble |

| 86 | Atlanta |

| 86 | Santa Monica |

| 87 | Grand Prairie |

| 92 | Memphis |

| >100 | APO |

| >100 | Anaheim |

| >100 | Arlington TX |

| >100 | Athens |

| >100 | Austin |

| >100 | Baltimore |

| >100 | Boulder |

| >100 | The Bronx |

| >100 | Brooklyn |

| >100 | College Station |

| >100 | Dallas |

| >100 | Detroit |

| >100 | Fort Lauderdale |

| >100 | Fort Worth |

| >100 | Hialeah |

| >100 | Hollywood FL |

| >100 | Honolulu |

| >100 | Houston |

| >100 | Irving |

| >100 | Los Angeles |

| >100 | Lubbock |

| >100 | Mesquite |

| >100 | Miami |

| >100 | Nashville |

| >100 | Newark |

| >100 | Oakland |

| >100 | Portland OR |

| >100 | Provo |

| >100 | Rochester |

| >100 | Sacramento |

| >100 | San Francisco |

| >100 | Santa Ana |

Presumably none of this will bother Taylor, but "people who are not going to listen disproportionately are going to not listen disproportionately" wouldn't fit the meter of the song very well, so I assume that's why she didn't mention it.

¶ City ranks by genre · 15 October 2014 listen/tech

For another way to look at the data from my examination of the distinctive music-listening of US cities, I ranked the top 10 cities by distinctive affiliation to some major genres.

acoustic pop

alternative country

alternative dance

bachata

banda

ccm

chillwave

contemporary country

country

crunk

dance pop

dirty south rap

duranguense

edm

electro house

folk

freak folk

g funk

hip hop

house

hurban

hyphy

indie folk

indie pop

indie rock

indietronica

jam band

jerk

latin

lo-fi

mariachi

norteno

nu gaze

outlaw country

pop

pop punk

progressive bluegrass

r&b

r-neg-b

ranchera

reggaeton

shimmer pop

stomp and holler

synthpop

trap music

west coast rap

worship

This might also be the preface for a volume of sociology essays.

acoustic pop

| 1 | Spokane |

| 2 | Knoxville |

| 3 | Grand Rapids |

| 4 | St. Paul |

| 5 | Norman |

| 6 | Birmingham |

| 7 | Nashville |

| 8 | Austin |

| 9 | Madison |

| 10 | Athens |

alternative country

| 1 | Nashville |

| 2 | Louisville |

| 3 | Raleigh |

| 4 | Frisco |

| 5 | Charleston |

| 6 | Fort Worth |

| 7 | Birmingham |

| 8 | College Station |

| 9 | Grand Prairie |

| 10 | Greenville |

alternative dance

| 1 | San Francisco |

| 2 | Santa Monica |

| 3 | Tucson |

| 4 | New York |

| 5 | Tempe |

| 6 | Pasadena |

| 7 | San Diego |

| 8 | Gainesville |

| 9 | Chicago |

| 10 | San Luis Obispo |

bachata

| 1 | Newark |

| 2 | The Bronx |

| 3 | Jersey City |

| 4 | Miami |

| 5 | Hollywood FL |

| 6 | Brooklyn |

| 7 | Fort Lauderdale |

| 8 | Hialeah |

| 9 | West Palm Beach |

| 10 | Tampa |

banda

| 1 | Mountain View |

| 2 | Mesquite |

| 3 | Irving |

| 4 | Newark |

| 5 | Concord |

| 6 | Oakland |

| 7 | Santa Ana |

| 8 | Anaheim |

| 9 | Bakersfield |

| 10 | Los Angeles |

ccm

| 1 | Springfield MO |

| 2 | Grand Rapids |

| 3 | Oklahoma City |

| 4 | Spokane |

| 5 | Birmingham |

| 6 | Tulsa |

| 7 | St. Paul |

| 8 | Colorado Springs |

| 9 | Knoxville |

| 10 | Norman |

chillwave

| 1 | San Francisco |

| 2 | Santa Monica |

| 3 | Portland OR |

| 4 | Seattle |

| 5 | Brooklyn |

| 6 | New York |

| 7 | Pasadena |

| 8 | New Orleans |

| 9 | Berkeley |

| 10 | San Diego |

contemporary country

| 1 | Des Moines |

| 2 | Lincoln |

| 3 | Omaha |

| 4 | Indianapolis |

| 5 | Columbia MO |

| 6 | Akron |

| 7 | APO |

| 8 | Dayton |

| 9 | Lexington |

| 10 | Albuquerque |

country

| 1 | APO |

| 2 | Indianapolis |

| 3 | Akron |

| 4 | Albuquerque |

| 5 | Des Moines |

| 6 | Omaha |

| 7 | Columbia MO |

| 8 | Lincoln |

| 9 | San Antonio |

| 10 | Dayton |

crunk

| 1 | Humble |

| 2 | Katy |

| 3 | Houston |

| 4 | Charlotte |

| 5 | Orlando |

| 6 | Baton Rouge |

| 7 | Farmington |

| 8 | Memphis |

| 9 | Irving |

| 10 | Tampa |

dance pop

| 1 | Baltimore |

| 2 | Greensboro |

| 3 | Detroit |

| 4 | Las Vegas |

| 5 | Philadelphia |

| 6 | Gilbert |

| 7 | Pompano Beach |

| 8 | Trenton |

| 9 | Wilmington DE |

| 10 | Atlanta |

dirty south rap

| 1 | Humble |

| 2 | Katy |

| 3 | Houston |

| 4 | Charlotte |

| 5 | Atlanta |

| 6 | Irving |

| 7 | Orlando |

| 8 | Farmington |

| 9 | Memphis |

| 10 | Arlington TX |

duranguense

| 1 | Mesquite |

| 2 | Irving |

| 3 | Mountain View |

| 4 | Arlington TX |

| 5 | Dallas |

| 6 | Newark |

| 7 | Jersey City |

| 8 | Concord |

| 9 | Houston |

| 10 | Oakland |

edm

| 1 | Irvine |

| 2 | Hoboken |

| 3 | San Jose |

| 4 | Fremont |

| 5 | Santa Clara |

| 6 | Berkeley |

| 7 | State College |

| 8 | Reno |

| 9 | Sunnyvale |

| 10 | Bellevue |

electro house

| 1 | Hoboken |

| 2 | Irvine |

| 3 | San Jose |

| 4 | Fremont |

| 5 | Santa Clara |

| 6 | Berkeley |

| 7 | New York |

| 8 | State College |

| 9 | Boston |

| 10 | Sunnyvale |

folk

| 1 | Nashville |

| 2 | Charleston |

| 3 | Louisville |

| 4 | Raleigh |

| 5 | Portland OR |

| 6 | Chapel Hill |

| 7 | Birmingham |

| 8 | Greenville |

| 9 | Knoxville |

| 10 | Wilmington NC |

freak folk

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Brooklyn |

| 3 | Seattle |

| 4 | Cambridge |

| 5 | San Francisco |

| 6 | Somerville |

| 7 | Santa Monica |

| 8 | Athens |

| 9 | Austin |

| 10 | Denton |

g funk

| 1 | Hayward |

| 2 | Concord |

| 3 | Oakland |

| 4 | Sacramento |

| 5 | Stockton |

| 6 | San Jose |

| 7 | Fresno |

| 8 | Fremont |

| 9 | Los Angeles |

| 10 | Whittier |

hip hop

| 1 | Hartford |

| 2 | Silver Spring |

| 3 | Worcester |

| 4 | Ann Arbor |

| 5 | Farmington |

| 6 | Philadelphia |

| 7 | Wilmington DE |

| 8 | Tampa |

| 9 | Boca Raton |

| 10 | Hyattsville |

house

| 1 | Hoboken |

| 2 | Irvine |

| 3 | San Jose |

| 4 | Fremont |

| 5 | Santa Clara |

| 6 | Berkeley |

| 7 | State College |

| 8 | Sunnyvale |

| 9 | Reno |

| 10 | Orange |

hurban

| 1 | Miami |

| 2 | Hollywood FL |

| 3 | Hialeah |

| 4 | Fort Lauderdale |

| 5 | Newark |

| 6 | West Palm Beach |

| 7 | Jersey City |

| 8 | The Bronx |

| 9 | El Paso |

| 10 | Miami Beach |

hyphy

| 1 | Concord |

| 2 | Hayward |

| 3 | Sacramento |

| 4 | Stockton |

| 5 | Oakland |

| 6 | Fresno |

| 7 | San Jose |

| 8 | Fremont |

| 9 | Santa Clara |

| 10 | San Francisco |

indie folk

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Somerville |

| 3 | Cambridge |

| 4 | Madison |

| 5 | Eugene |

| 6 | Spokane |

| 7 | Louisville |

| 8 | Milwaukee |

| 9 | New Haven |

| 10 | Durham |

indie pop

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Somerville |

| 3 | Austin |

| 4 | Cambridge |

| 5 | Chicago |

| 6 | New Orleans |

| 7 | Seattle |

| 8 | Eugene |

| 9 | Lawrence |

| 10 | Milwaukee |

indie rock

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Chicago |

| 3 | Cambridge |

| 4 | Somerville |

| 5 | Seattle |

| 6 | Austin |

| 7 | Columbus |

| 8 | Tempe |

| 9 | San Diego |

| 10 | St. Louis |

indietronica

| 1 | Santa Monica |

| 2 | San Francisco |

| 3 | Portland OR |

| 4 | Seattle |

| 5 | New York |

| 6 | San Diego |

| 7 | Bellevue |

| 8 | Pasadena |

| 9 | Anchorage |

| 10 | Brooklyn |

jam band

| 1 | Boulder |

| 2 | Athens |

| 3 | Denver |

| 4 | Fort Collins |

| 5 | Charleston |

| 6 | Birmingham |

| 7 | Columbia SC |

| 8 | Baton Rouge |

| 9 | New Orleans |

| 10 | Wilmington NC |

jerk

| 1 | Stockton |

| 2 | Hayward |

| 3 | Sacramento |

| 4 | Oakland |

| 5 | Concord |

| 6 | Fremont |

| 7 | Corona |

| 8 | San Jose |

| 9 | Bakersfield |

| 10 | Phoenix |

latin

| 1 | El Paso |

| 2 | Miami |

| 3 | Hialeah |

| 4 | Miami Beach |

| 5 | Hollywood FL |

| 6 | Fort Lauderdale |

| 7 | Boca Raton |

| 8 | West Palm Beach |

| 9 | Mesquite |

| 10 | Jersey City |

lo-fi

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Austin |

| 3 | Seattle |

| 4 | Cambridge |

| 5 | Chicago |

| 6 | Somerville |

| 7 | Brooklyn |

| 8 | Santa Monica |

| 9 | Cincinnati |

| 10 | Louisville |

mariachi

| 1 | Mountain View |

| 2 | Newark |

| 3 | Mesquite |

| 4 | Irving |

| 5 | Concord |

| 6 | Jersey City |

| 7 | Oakland |

| 8 | Santa Ana |

| 9 | El Paso |

| 10 | Dallas |

norteno

| 1 | Mountain View |

| 2 | Mesquite |

| 3 | Irving |

| 4 | Newark |

| 5 | Concord |

| 6 | Oakland |

| 7 | Santa Ana |

| 8 | Anaheim |

| 9 | Bakersfield |

| 10 | Houston |

nu gaze

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Brooklyn |

| 3 | Santa Monica |

| 4 | Seattle |

| 5 | San Francisco |

| 6 | San Diego |

| 7 | Pasadena |

| 8 | Lawrence |

| 9 | New Orleans |

| 10 | New York |

outlaw country

| 1 | Fort Worth |

| 2 | Grand Prairie |

| 3 | Frisco |

| 4 | College Station |

| 5 | Lewisville |

| 6 | Lubbock |

| 7 | Spring |

| 8 | Dallas |

| 9 | San Antonio |

| 10 | Arlington TX |

pop

| 1 | Gilbert |

| 2 | Pompano Beach |

| 3 | Chandler |

| 4 | Trenton |

| 5 | Las Vegas |

| 6 | Plano |

| 7 | Santa Clara |

| 8 | Anchorage |

| 9 | Vancouver |

| 10 | Fresno |

pop punk

| 1 | Mesa |

| 2 | Virginia Beach |

| 3 | Trenton |

| 4 | Chandler |

| 5 | Buffalo |

| 6 | Gilbert |

| 7 | Pittsburgh |

| 8 | Tucson |

| 9 | Colorado Springs |

| 10 | East Lansing |

progressive bluegrass

| 1 | Denver |

| 2 | Boulder |

| 3 | Fort Collins |

| 4 | Raleigh |

| 5 | Charleston |

| 6 | Knoxville |

| 7 | Chapel Hill |

| 8 | Greenville |

| 9 | Louisville |

| 10 | Nashville |

r&b

| 1 | Baltimore |

| 2 | Detroit |

| 3 | Atlanta |

| 4 | Greensboro |

| 5 | Memphis |

| 6 | Philadelphia |

| 7 | Hyattsville |

| 8 | Richmond |

| 9 | Norfolk |

| 10 | Las Vegas |

r-neg-b

| 1 | San Francisco |

| 2 | Santa Monica |

| 3 | New York |

| 4 | Brooklyn |

| 5 | Providence |

| 6 | Seattle |

| 7 | Pasadena |

| 8 | Portland OR |

| 9 | Baltimore |

| 10 | Hyattsville |

ranchera

| 1 | Mountain View |

| 2 | Newark |

| 3 | Mesquite |

| 4 | Irving |

| 5 | Concord |

| 6 | Jersey City |

| 7 | Oakland |

| 8 | Santa Ana |

| 9 | Dallas |

| 10 | Los Angeles |

reggaeton

| 1 | Hialeah |

| 2 | Miami |

| 3 | Hollywood FL |

| 4 | Fort Lauderdale |

| 5 | West Palm Beach |

| 6 | Orlando |

| 7 | Boca Raton |

| 8 | Miami Beach |

| 9 | Tampa |

| 10 | Jersey City |

shimmer pop

| 1 | St. Louis |

| 2 | Santa Monica |

| 3 | Lawrence |

| 4 | San Francisco |

| 5 | Kansas City |

| 6 | Overland Park |

| 7 | Littleton |

| 8 | Colorado Springs |

| 9 | Aurora |

| 10 | Bellevue |

stomp and holler

| 1 | Portland OR |

| 2 | Somerville |

| 3 | Louisville |

| 4 | Minneapolis |

| 5 | Wilmington NC |

| 6 | Cambridge |

| 7 | Eugene |

| 8 | Madison |

| 9 | Milwaukee |

| 10 | Spokane |

synthpop

| 1 | San Francisco |

| 2 | Santa Monica |

| 3 | New York |

| 4 | Tucson |

| 5 | Pasadena |

| 6 | San Diego |

| 7 | Tempe |

| 8 | Bellevue |

| 9 | Chicago |

| 10 | Gainesville |

trap music

| 1 | Charlotte |

| 2 | Memphis |

| 3 | Humble |

| 4 | Richmond |

| 5 | Farmington |

| 6 | Silver Spring |

| 7 | Orlando |

| 8 | Toledo |

| 9 | Baton Rouge |

| 10 | Katy |

west coast rap

| 1 | Hayward |

| 2 | Concord |

| 3 | Sacramento |

| 4 | Oakland |

| 5 | Stockton |

| 6 | San Jose |

| 7 | Fresno |

| 8 | Fremont |

| 9 | Los Angeles |

| 10 | Whittier |

worship

| 1 | Springfield MO |

| 2 | Grand Rapids |

| 3 | Spokane |

| 4 | Tulsa |

| 5 | Birmingham |

| 6 | St. Paul |

| 7 | Oklahoma City |

| 8 | Greenville |

| 9 | Knoxville |

| 10 | Murfreesboro |

This might also be the preface for a volume of sociology essays.

¶ Sounds in Color · 8 October 2014 listen/tech

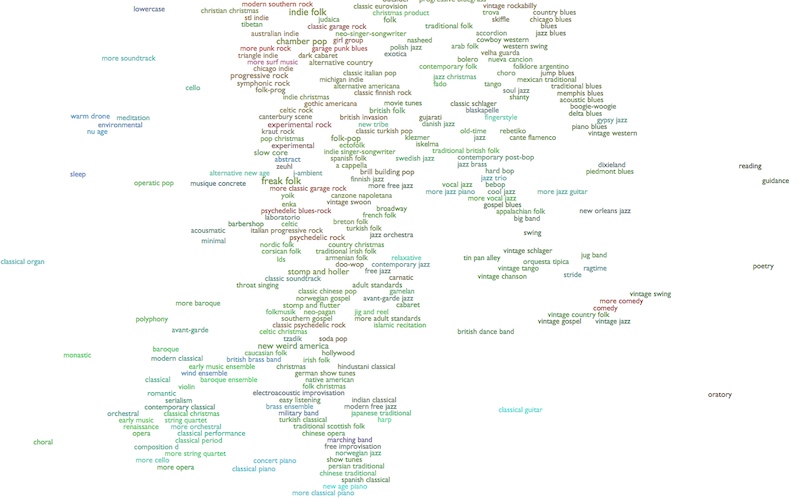

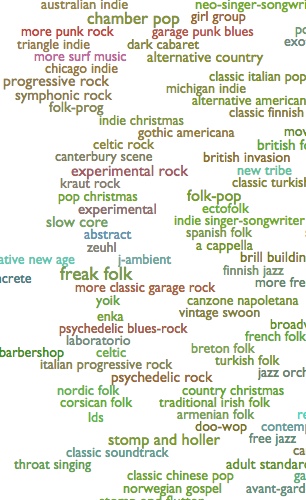

Every Noise at Once has long existed in shades of gray. This isn't because I don't like colors. I've actually tried a few different ways to add color, mostly through inelegant expedients, but none of them seemed to me to be adding more clarity than confusion.

I'm not entirely certain this one doesn't also suffer that flaw, but in the spirit of experimentation, I'm going to go ahead and publish it. If it makes us unhappy, I can always go back to gray. So here:

The idea is to semi-subliminally surface some of the other analytical dimensions from the underlying music space, beyond the two that drive the XY axes, so that there's a little less visual flattening.

For example, in the section on the right, above, you can see the reddish color running from "garage punk blues" to "experimental rock" to "more classic garage rock" and "psychedelic blues-rock", and the light blue linking "alternative new age" to "abstract" to "new tribe". These are good associative threads.

And the maps within each genre (psychedelic blues-rock on the left, below, and abstract on the right) show both overall corresponding tints, and variable degrees of internal uniformity:

Logistically, this works by mapping three additional acoustic metrics into the red, green and blue color-channels. I arrived at this particular combination through not-at-all-exhaustive experimentation, so maybe I'll come up with a better one, but for the moment red is energy, green is dynamic variation, and blue is instrumentalness. I don't recommend trying to think too hard about this, as the combinatory effects are kind of hard to parse, but it gives your eye things to follow. As data-presentation this is rather undisciplined, but as computational evocation it seems potentially interesting nonetheless.

Which you could say of music, too.

I'm not entirely certain this one doesn't also suffer that flaw, but in the spirit of experimentation, I'm going to go ahead and publish it. If it makes us unhappy, I can always go back to gray. So here:

The idea is to semi-subliminally surface some of the other analytical dimensions from the underlying music space, beyond the two that drive the XY axes, so that there's a little less visual flattening.

For example, in the section on the right, above, you can see the reddish color running from "garage punk blues" to "experimental rock" to "more classic garage rock" and "psychedelic blues-rock", and the light blue linking "alternative new age" to "abstract" to "new tribe". These are good associative threads.

And the maps within each genre (psychedelic blues-rock on the left, below, and abstract on the right) show both overall corresponding tints, and variable degrees of internal uniformity:

Logistically, this works by mapping three additional acoustic metrics into the red, green and blue color-channels. I arrived at this particular combination through not-at-all-exhaustive experimentation, so maybe I'll come up with a better one, but for the moment red is energy, green is dynamic variation, and blue is instrumentalness. I don't recommend trying to think too hard about this, as the combinatory effects are kind of hard to parse, but it gives your eye things to follow. As data-presentation this is rather undisciplined, but as computational evocation it seems potentially interesting nonetheless.

Which you could say of music, too.

¶ Post-Neo-Traditional Pop Post-Thing · 29 September 2014 essay/listen/tech

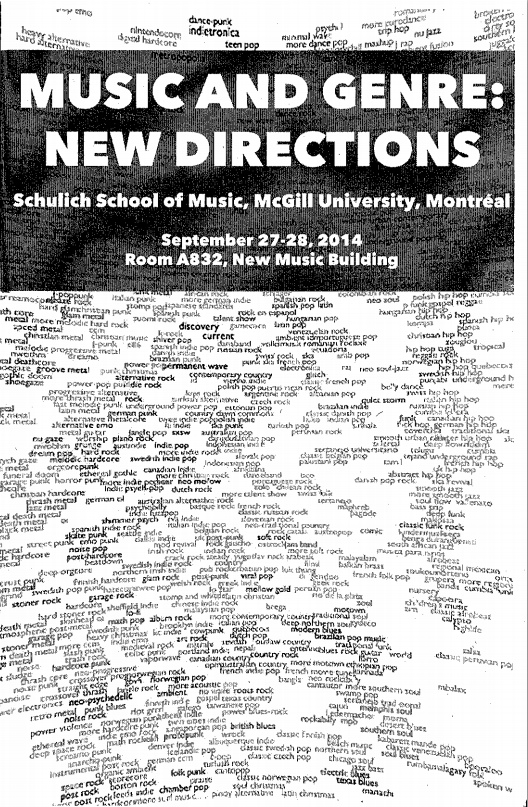

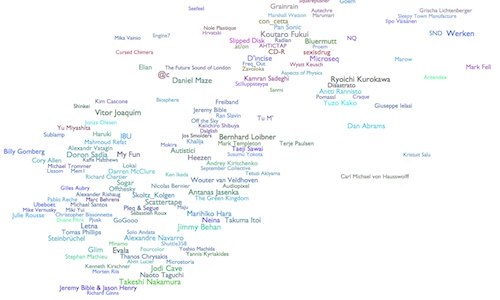

As part of a conference on Music and Genre at McGill University in Montreal, over this past weekend, I served as the non-academic curiosity at the center of a round-table discussion about the nature of musical genres, and of the natures of efforts to understand genres, and of the natures of efforts to understand the efforts to understand genres. Plus or minus one or two levels of abstraction, I forget exactly.

My "talk" to open this conversation was not strictly scripted to begin with, and I ended up rewriting my oblique speaking notes more or less over from scratch as the day was going on, anyway. One section, which I added as I listened to other people talk about the kinds of distinctions that "genres" represent, attempted to list some of the kinds of genres I have in my deliberately multi-definitional genre map. There ended up being so many of these that I mentioned only a selection of them during the talk. So here, for extended (potential) amusement, is the whole list I had on my screen:

Kinds of Genres

(And note that this isn't even one kind of kind of genre...)

- conventional genre (jazz, reggae)

- subgenre (calypso, sega, samba, barbershop)

- region (malaysian pop, lithumania)

- language (rock en espanol, hip hop tuga, telugu, malayalam)

- historical distance (vintage swing, traditional country)

- scene (slc indie, canterbury scene, juggalo, usbm)

- faction (east coast hip hop, west coast rap)

- aesthetic (ninja, complextro, funeral doom)

- politics (riot grrrl, vegan straight edge, unblack metal)

- aspirational identity (viking metal, gangster rap, skinhead oi, twee pop)

- retrospective clarity (protopunk, classic peruvian pop, emo punk)

- jokes that stuck (crack rock steady, chamber pop, fourth world)

- influence (britpop, italo disco, japanoise)

- micro-feud (dubstep, brostep, filthstep, trapstep)

- technology (c64, harp)

- totem (digeridu, new tribe, throat singing, metal guitar)

- isolationism (faeroese pop, lds, wrock)

- editorial precedent (c86, zolo, illbient)

- utility (meditation, chill-out, workout, belly dance)

- cultural (christmas, children's music, judaica)

- occasional (discofox, qawaali, disco polo)

- implicit politics (chalga, nsbm, dangdut)

- commerce (coverchill, guidance)

- assumed listening perspective (beatdown, worship, comic)

- private community (orgcore, ectofolk)

- dominant features (hip hop, metal, reggaeton)

- period (early music, ska revival)

- perspective of provenance (classical (composers), orchestral (performers))

- emergent self-identity (skweee, progressive rock)

- external label (moombahton, laboratorio, fallen angel)

- gender (boy band, girl group)

- distribution (viral pop, idol, commons, anime score, show tunes)

- cultural institution (tin pan alley, brill building pop, nashville sound)

- mechanism (mashup, hauntology, vaporwave)

- radio format (album rock, quiet storm, hurban)

- multiple dimensions (german ccm, hindustani classical)

- marketing (world music, lounge, modern classical, new age)

- performer demographics (military band, british brass band)

- arrangement (jazz trio, jug band, wind ensemble)

- competing terminology (hip hop, rap; mpb, brazilian pop music)

- intentions (tribute, fake)

- introspective fractality (riddim, deep house, chaotic black metal)

- opposition (alternative rock, r-neg-b, progressive bluegrass)

- otherness (noise, oratory, lowercase, abstract, outsider)

- parallel terminology (gothic symphonic metal, gothic americana, gothic post-punk; garage rock, uk garage)

- non-self-explanatory (fingerstyle, footwork, futurepop, jungle)

- invented distinctions (shimmer pop, shiver pop; soul flow, flick hop)

- nostalgia (new wave, no wave, new jack swing, avant-garde, adult standards)

- defense (relaxative, neo mellow)

That was at the beginning of the talk. At the end I had a different attempt at an amusement prepared, which was a short outline of my mental draft of the paper I would write about genre evolution, if I wrote papers. In a way this is also a way of listing kinds of kinds of things:

The Every-Noise-at-Once Unified Theory of Musical Genre Evolution

And it would be awesome.

[Also, although I was the one glaringly anomalous non-academic at this academic conference, let posterity record the cover of the conference program.]

My "talk" to open this conversation was not strictly scripted to begin with, and I ended up rewriting my oblique speaking notes more or less over from scratch as the day was going on, anyway. One section, which I added as I listened to other people talk about the kinds of distinctions that "genres" represent, attempted to list some of the kinds of genres I have in my deliberately multi-definitional genre map. There ended up being so many of these that I mentioned only a selection of them during the talk. So here, for extended (potential) amusement, is the whole list I had on my screen:

Kinds of Genres

(And note that this isn't even one kind of kind of genre...)

- conventional genre (jazz, reggae)

- subgenre (calypso, sega, samba, barbershop)

- region (malaysian pop, lithumania)

- language (rock en espanol, hip hop tuga, telugu, malayalam)

- historical distance (vintage swing, traditional country)

- scene (slc indie, canterbury scene, juggalo, usbm)

- faction (east coast hip hop, west coast rap)

- aesthetic (ninja, complextro, funeral doom)

- politics (riot grrrl, vegan straight edge, unblack metal)

- aspirational identity (viking metal, gangster rap, skinhead oi, twee pop)

- retrospective clarity (protopunk, classic peruvian pop, emo punk)

- jokes that stuck (crack rock steady, chamber pop, fourth world)

- influence (britpop, italo disco, japanoise)

- micro-feud (dubstep, brostep, filthstep, trapstep)

- technology (c64, harp)

- totem (digeridu, new tribe, throat singing, metal guitar)

- isolationism (faeroese pop, lds, wrock)

- editorial precedent (c86, zolo, illbient)

- utility (meditation, chill-out, workout, belly dance)

- cultural (christmas, children's music, judaica)

- occasional (discofox, qawaali, disco polo)

- implicit politics (chalga, nsbm, dangdut)

- commerce (coverchill, guidance)

- assumed listening perspective (beatdown, worship, comic)

- private community (orgcore, ectofolk)

- dominant features (hip hop, metal, reggaeton)

- period (early music, ska revival)

- perspective of provenance (classical (composers), orchestral (performers))

- emergent self-identity (skweee, progressive rock)

- external label (moombahton, laboratorio, fallen angel)

- gender (boy band, girl group)

- distribution (viral pop, idol, commons, anime score, show tunes)

- cultural institution (tin pan alley, brill building pop, nashville sound)

- mechanism (mashup, hauntology, vaporwave)

- radio format (album rock, quiet storm, hurban)

- multiple dimensions (german ccm, hindustani classical)

- marketing (world music, lounge, modern classical, new age)

- performer demographics (military band, british brass band)

- arrangement (jazz trio, jug band, wind ensemble)

- competing terminology (hip hop, rap; mpb, brazilian pop music)

- intentions (tribute, fake)

- introspective fractality (riddim, deep house, chaotic black metal)

- opposition (alternative rock, r-neg-b, progressive bluegrass)

- otherness (noise, oratory, lowercase, abstract, outsider)

- parallel terminology (gothic symphonic metal, gothic americana, gothic post-punk; garage rock, uk garage)

- non-self-explanatory (fingerstyle, footwork, futurepop, jungle)

- invented distinctions (shimmer pop, shiver pop; soul flow, flick hop)

- nostalgia (new wave, no wave, new jack swing, avant-garde, adult standards)

- defense (relaxative, neo mellow)

That was at the beginning of the talk. At the end I had a different attempt at an amusement prepared, which was a short outline of my mental draft of the paper I would write about genre evolution, if I wrote papers. In a way this is also a way of listing kinds of kinds of things:

The Every-Noise-at-Once Unified Theory of Musical Genre Evolution

- There is a status quo;

- Somebody becomes dissatisfied with it;

- Several somebodies find common ground in their various dissatisfactions;

- Somebody gives this common ground a name, and now we have Thing;

- The people who made thing before it was called Thing are now joined by people who know Thing as it is named, and have thus set out to make Thing deliberately, and now we have Thing and Modern Thing, or else Classic Thing and Thing, depending on whether it happened before or after we graduated from college;

- Eventually there's enough gravity around Thing for people to start trying to make Thing that doesn't get sucked into the rest of Thing, and thus we get Alternative Thing, which is the non-Thing thing that some people know about, and Deep Thing, which is the non-Thing thing that only the people who make Deep Thing know;

- By now we can retroactively identify Proto-Thing, which is the stuff before Thing that sounds kind of thingy to us now that we know Thing;

- Thing eventually gets reintegrated into the mainstream, and we get Pop Thing;

- Pop Thing tarnishes the whole affair for some people, who head off grumpily into Post Thing;

- But Post Thing is kind of dreary, and some people set out to restore the original sense of whatever it was, and we get Neo-Thing;

- Except Neo-Thing isn't quite the same as the original Thing, so we get Neo-Traditional Thing, for people who wish none of this ever happened except the original Thing;

- But Neo-Thing and Neo-Traditional Thing are both kind of precious, and some people who like Thing still also want to be rock stars, and so we get Nu Thing;

- And this is all kind of fractal, so you could search-and-replace Thing with Post Thing or Pop Thing or whatever, and after a couple iterations you can quickly end up with Post-Neo-Traditional Pop Post-Thing.

And it would be awesome.

[Also, although I was the one glaringly anomalous non-academic at this academic conference, let posterity record the cover of the conference program.]