30 June 2005 to 1 June 2005

¶ 30 June 2005

Zapruder Point: The O.M. (0.9M mp3)

from It's Always the Quiet Ones

I loaded the CD-changer in my car before the trip, so interspersed with all the new Japanese pop and trip-photo sorting and back-at-work denial and willful continuing other-cultural immersion, I've been hearing a few records I was pondering before I left. I'm dancing around to ultra-produced big-corporate techno-pop in a language I only sporadically understand and even less often actually empathize with, but I'm also standing still, humming small, wistful, under-produced, uncalculated reasons for being home to feel right.

from It's Always the Quiet Ones

I loaded the CD-changer in my car before the trip, so interspersed with all the new Japanese pop and trip-photo sorting and back-at-work denial and willful continuing other-cultural immersion, I've been hearing a few records I was pondering before I left. I'm dancing around to ultra-produced big-corporate techno-pop in a language I only sporadically understand and even less often actually empathize with, but I'm also standing still, humming small, wistful, under-produced, uncalculated reasons for being home to feel right.

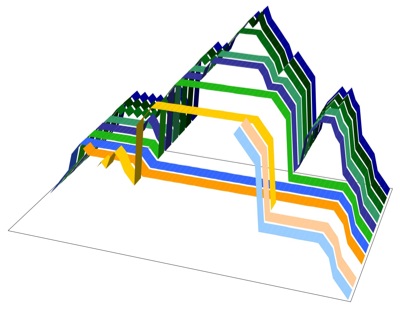

¶ our trip as a movement of objects · 26 June 2005

¶ telegram from the future · 26 June 2005

It is 12:14am on Sunday in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. About 30 hours ago it was 7am on Saturday in Kyoto, Japan, so after two buses, two trains, two planes and too many benches to count B and I are well into Sunday afternoon. Time-travel is possible, but you end up far too tired to think of any clever way to exploit it. We're going to sleep now, and tomorrow it will finally be today again.

¶ telegram from Kyoto · 23 June 2005

If I had 1001 40-armed guardians watching over me I'd probably be more Zen, too.

¶ telegram from Ubud · 21 June 2005

From being anomalous and anonymous, we have gone to being obvious and implored. Bali is both stunning and desperate in nearly every frame. "Will you come back to Bali?" is the fourth question everyone asks us, and we've barely even arrived. Tropical aquariums are now ruined for me, wider roads now enchanted. An oceanside palace for 4 in Pemuteran costs more than a bed-size room in Shinjuku, but only by about $4. Which is about 50 cents for each form in which I ate bananas.

The geckos and B and I all send our love.

The geckos and B and I all send our love.

¶ telegram from Shinjuku · 13 June 2005

Hi from the other side of the planet. So many people, so many noodles, so few days. Tokyo is just like San Francisco if we let ourselves be in New York, and just like Mars when I try to pretend I'm Martian. This morning I told a woman I needed to read the drink list and she moved a tray off of it, so apparently my Japanese isn't entirely useless. But I recognize three kanji in ten, understand one whole warning sign in twenty, and almost never have any idea what people are saying to me unless I could have deduced it from context anyway.

Totally cool.

Totally cool.

¶ 9 June 2005

For the record, just a few hours before I leave on the longest trip I've yet taken:

My biggest fear is that Tokyo won't feel strange enough.

My biggest fear is that Tokyo won't feel strange enough.

¶ 6 June 2005

it was that night on the phone

you said "let's kill the mod revival"

to some applause, and then you paused

as if almost to say "I love you"

- Tullycraft: "Polaroids From Mars" (from Disenchanted Hearts Unite)

Staying alive is retaining the willingness and ability to surmise, in every tiny pause, that something amazing is yearning to happen.

you said "let's kill the mod revival"

to some applause, and then you paused

as if almost to say "I love you"

- Tullycraft: "Polaroids From Mars" (from Disenchanted Hearts Unite)

Staying alive is retaining the willingness and ability to surmise, in every tiny pause, that something amazing is yearning to happen.

the brilliant green: Rainy days never stays (album mix) (1.8M mp3)

In anticipation of my imminent first visit to Japan, one of my very favorite frothy Japanese pop songs.

In anticipation of my imminent first visit to Japan, one of my very favorite frothy Japanese pop songs.