22 January 2006 to 13 January 2006

¶ ici and aqui · 22 January 2006

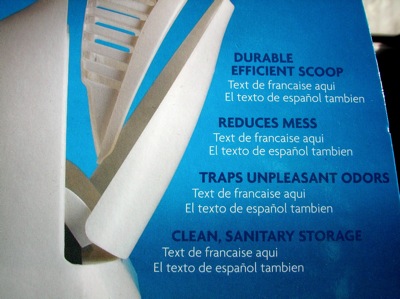

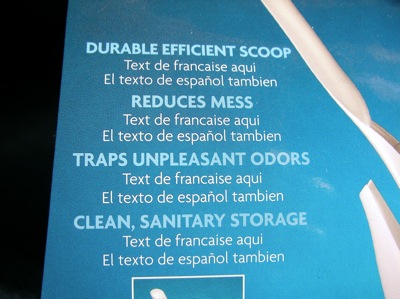

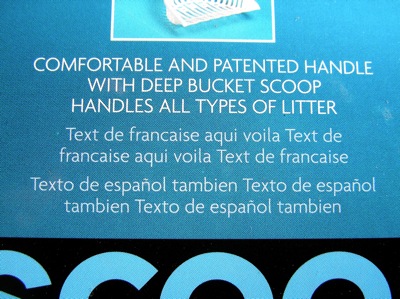

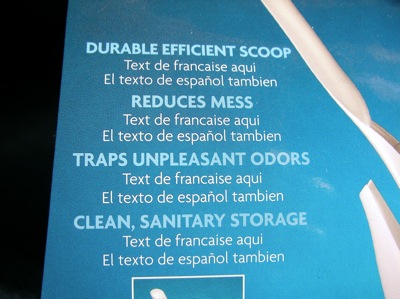

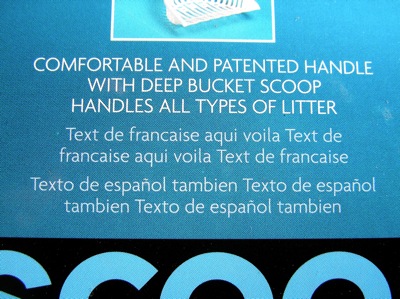

See if you can spot the production step the makers of this litter scoop forgot.

I would also like to see the paperwork for the "patented handle".

I would also like to see the paperwork for the "patented handle".

Lincolnville: Heavenly Calm (1.3M mp3)

Because I was revisiting the C section of my shelves today...

Because I was revisiting the C section of my shelves today...

¶ Content and Presentation Are 3 · 18 January 2006 essay/tech

At the moment, the tools for online publishing were mostly designed by software people for an audience of other software people, so it shouldn't be too surprising that by real (i.e., pre-/non- online) publishing standards most of them are not only fairly terrible in particulars, but basically comprehensively alien and unresponsive down to the conceptual model.

The reason the HTML-tables-vs-CSS-blocks war wasn't over ten minutes after CSS was invented, for example, is that the CSS float/span/margin/escape model chose (more in ignorance than defiance, I'm sure) its own internal geometrical cleverness over the potential applicability of centuries of conventional information design. The most basic tool of scalable information design is and has always been the layout grid. CSS is capable of producing a simple layout grid, but not simply. Arguably it's even harder to recognize a page layout by reading its CSS than it is to write the CSS. Structural elements are structural by convention if you're lucky, coincidence if you aren't, and certainly not by nature, and are unavoidably cluttered by non-structural formatting elements.

An HTML table isn't a good tool for page layout, either, but for the most part a simple layout grid can be expressed by a simple HTML table, and with decent code-indentation it is possible to more or less grasp the presentation structure of a simple table by looking at its code. The fact that tables require the content and the structure to be intertwined is a huge problem, and the fundamental misconception of the scheme emerges the moment any kind of table-nesting is required for page-structural and/or content-structural reasons. The non-programmer's mental model of a box is an actual box. You can put small actual boxes inside larger ones. If you forget to put a bottom on a small box inside a large box, you get a bottomless small box inside a normal large box, not a deformed small box falling out of the bottom of a mangled large box. Nobody, not even a programmer, intuitively thinks of object construction procedurally, and nobody but a programmer (and not most of those) would want to.

Ironically, painfully, the closest thing in current web technology to simple modeling of simple presentation structure is technically the most flawed: frames. I would recommend their use for almost no public purpose, and frameset code is no pleasure to look at, either, but at least frame definition is separated from content (too separated, in fact, but separation is still a good idea), and its grammar operates by explicitly specifying structure from the outside in (with recursion, albeit awkwardly), rather than calculating it by implication from the inside out. If frames had been defined as page (and sub-page) elements pre-declaring layout structure, rather than window elements that contain content pages by reference, we might have had something.

While we're redoing the layout model, though, we also need to fix our basic misunderstanding of the natural structure of repeatable content presentation. Any remotely enlightened programmer "knows" that content should be separated from presentation, but these are actually three things, not two: content, presentation structure, and actual formatting, and in practice the formatting can usually be further separated into content formatting (the formatting of the information unique to this content node) and page layout (the site-identity and navigation and other framing stuff displayed around it but conceptually invoked from context).

Take this furialog entry itself, for example. Its content structure includes a title, a display date, a publication timestamp, a set of tags and a content block. This content structure is then mapped into a presentation structure for this web page which is quite a bit simpler: just a header and a body. The title, display date and tags are concatenated into a single formatted block for presentation purposes, and the timestamp is not (in this format) presented at all. The formatting rules, then, are applied to the presentation structure, not the content structure. This is important, because elsewhere on this site content with very different content structures gets mapped into the same presentation structure, subject to the same formatting rules, and thus it is possible for me to define a single rule-set that drives the middle layers of the production of all my content, a single page-layout that drives the outer layers, and appropriate extensions to which the sub-formatting of special-purpose inner blocks like tables and photosets can be delegated.

The usefulness of RSS, similarly, is largely due to the fact that it defines a common presentation structure into which dissimilar content structures may be mapped. Different feed sources may put semantically different and/or compound information into the title and description fields, but the writing software doesn't have to know or care about the formatting rules, and the reading software doesn't have to know or care about the content structure. The drawback of using presentation structure as an interchange medium, of course, is that the reading software can't get the original content structure even if it could do something interesting with it. Human readers can re-interpolate it, but for the machines RSS tends to be lossy.

This was also, maybe obviously, the original design concept for HTML: standardize a presentation structure that can then act as universal intermediary between content and screen. RSS gets away with its limitations because it's an alternate channel, but as the web emerged, HTML was the web, and universal intermediation quickly proved unsatisfying in both directions: writers couldn't exercise enough control over formatting when they needed or wanted to (and programmers often assume "want" is always the right word here, but publishers understand that publishing is different than just writing), and machines couldn't add enough processing insight without finer-grained and/or domain-specific data schema.

Here, then, are some of the elements of the new model I want, some of what, from twenty years of working with information in both publishing and software spheres (and this isn't what I thought after ten, so maybe it won't be what I think after forty, but is that because I change, or because the world does?), I believe the whole system needs in order to fulfill its potential as a medium at once for direct human communication and human understanding supplemented by computer reasoning:

- Not only should all meaningful content begin in its own schema, but this machine-parsable content structure should, inherently and automatically, underlie and accompany the human-visible presentation and formatting of all information. Imagine, if this were our only problem, adding an Elemental XML section to every HTML page, so that each page would carry its pre-presentation data in addition to all of its other markup, and splitting the View Source command into View Presentation Code and View Source Data to offer different tools for each. (Microformats are a similarly motivated effort, establishing presentation-structure conventions for particular kinds of content structure, but conflating the two kinds of structure is only reasonable as a short-term tactical compromise in a system where there's no good way to separate them, anyway.)

- The mapping of content structure into presentation structure must be so trivially easy, and such an obvious entry into a richly distributed universe of sophisticated standard lexicons and templates, that nobody will even be tempted to try to skip the step by pretending that their content doesn't have any other structure than its presentation. Imagine, as you're publishing something, that you could chose dynamically from not only your own repertoire of formats and the templates provided by your authoring software, but from a social universe of templates, of all granularities, available from anyone who has one to offer. The laborious specific control of your own formatting, or the flexible custom extension of your presentation structure, should be optional opportunities for the motivated, not required burdens of participation.

- The layout model should be based on recursive containment from the outside in (probably with layers, for graphic depth). Exceptional behavior, like violating margins, must be declared explicitly, not arise from routine errors in normal use. It should be trivial to map one element of presentation structure into one formatting container, to flow multiple elements of presentation structure into one formatting container, or to flow one or more elements of presentation structure through an arbitrarily linked series of formatting containers. We've learned a lot about UI and usability since Quark and PageMaker were invented, and not everything we ever wanted to do in books and magazines applies the same way on a screen or in an interactive environment, but in many ways the screen world is only now approaching the point where print was before computers, so as is already beginning to sink in about typography, more old lessons apply than not.

- Where the new medium has new abilities, our tools should be granting new powers to us, not demanding new chores. AJAX is a clever retrofit of what should have been a native idiom. Forget paging vs scrolling, Google Maps is how everything offscreen should work, the computers dealing with computer constraints like bandwidth and memory without bringing people into issues that don't concern people. And if content were encapsulated intelligently, it wouldn't take Flash or iframes or scripts to make a piece of a page do things a whole page can already do. The web is a bad application environment kludged onto a bad publishing environment, and it ought to be a composite environment in which publishers realize that sometimes they are publishing applications and experiences and devices, not just pictures and words.

- The separation of content, presentation structure and formatting is necessary for everyone's purposes, not just the auteurs and the programmers and the machines. Good, reusable, maintainable presentation design, even when it's done by dedicated designers, should always work first from presentation structure to formatting rules. The handcrafting of individual exceptions should be an elaboration on a framework of rules, not a repetitive substitute for making the effort to understand patterns. I see way too much CSS code that specifies individual pixel-unit fonts and margins and paddings for every single id-numbered div in an entire page (or, worse, for every id-numbered div in a whole set of pages, so that the style-sheet can be "reused" across all of them). Sometimes this is a result of having misused the (X)HTML to model the content structure, rather than the presentation structure, so that the formats and the selectors don't line up right, but I bet it's more often just laziness. It's always faster to add a pixel than to generalize a rule about why, but it takes an incredibly tiny number of exceptions to complicate a rule-set so irretrievably that it can only be modified by further exceptions. For all but the rarest purposes where chaos is the order, the fewer rules the better, and the square of the fewer exceptions the better.

But fine. No matter what you credit as partial precedence, ubiquitous electronic publishing and communication as social infrastructure are at best in their adolescence, and it's amazing we've gotten this far with these primitive tools. The willingnesses to restart and rebuild are in our character, just as surely as myopia and impatience are our curses. Generations are how we learn.

So yes, this means starting over, but the new ways, when they're right, are easier than the old ones, and we only shrink from them out of fear of change. In place of the current HTML/CSS information foundation we will have data (content structure), mapping (content structure to presentation structure), page layout (the containers through which the presentation structures flow) and formatting (typography, color, spacing, ornamentation and illustration within those containers). Any of these can be implied from defaults (set by the reader, writer or both), included by reference to external sources, included by recursion, included conditionally by context, or defined inline. Most of this will still be mediated by tools for most people, but the tools will be simpler and more powerful, and will let us focus more on what we're saying to each other, and less on how.

And since the new way delivers both the formatting and the semantics, this will be a practical revolution that actually subsumes a theoretical one, better human communication interleaved with better machine communication, and thus the foundation for both better shopping and the dream of the internet being something qualitatively more profound and transformative than shopping.

The reason the HTML-tables-vs-CSS-blocks war wasn't over ten minutes after CSS was invented, for example, is that the CSS float/span/margin/escape model chose (more in ignorance than defiance, I'm sure) its own internal geometrical cleverness over the potential applicability of centuries of conventional information design. The most basic tool of scalable information design is and has always been the layout grid. CSS is capable of producing a simple layout grid, but not simply. Arguably it's even harder to recognize a page layout by reading its CSS than it is to write the CSS. Structural elements are structural by convention if you're lucky, coincidence if you aren't, and certainly not by nature, and are unavoidably cluttered by non-structural formatting elements.

An HTML table isn't a good tool for page layout, either, but for the most part a simple layout grid can be expressed by a simple HTML table, and with decent code-indentation it is possible to more or less grasp the presentation structure of a simple table by looking at its code. The fact that tables require the content and the structure to be intertwined is a huge problem, and the fundamental misconception of the scheme emerges the moment any kind of table-nesting is required for page-structural and/or content-structural reasons. The non-programmer's mental model of a box is an actual box. You can put small actual boxes inside larger ones. If you forget to put a bottom on a small box inside a large box, you get a bottomless small box inside a normal large box, not a deformed small box falling out of the bottom of a mangled large box. Nobody, not even a programmer, intuitively thinks of object construction procedurally, and nobody but a programmer (and not most of those) would want to.

Ironically, painfully, the closest thing in current web technology to simple modeling of simple presentation structure is technically the most flawed: frames. I would recommend their use for almost no public purpose, and frameset code is no pleasure to look at, either, but at least frame definition is separated from content (too separated, in fact, but separation is still a good idea), and its grammar operates by explicitly specifying structure from the outside in (with recursion, albeit awkwardly), rather than calculating it by implication from the inside out. If frames had been defined as page (and sub-page) elements pre-declaring layout structure, rather than window elements that contain content pages by reference, we might have had something.

While we're redoing the layout model, though, we also need to fix our basic misunderstanding of the natural structure of repeatable content presentation. Any remotely enlightened programmer "knows" that content should be separated from presentation, but these are actually three things, not two: content, presentation structure, and actual formatting, and in practice the formatting can usually be further separated into content formatting (the formatting of the information unique to this content node) and page layout (the site-identity and navigation and other framing stuff displayed around it but conceptually invoked from context).

Take this furialog entry itself, for example. Its content structure includes a title, a display date, a publication timestamp, a set of tags and a content block. This content structure is then mapped into a presentation structure for this web page which is quite a bit simpler: just a header and a body. The title, display date and tags are concatenated into a single formatted block for presentation purposes, and the timestamp is not (in this format) presented at all. The formatting rules, then, are applied to the presentation structure, not the content structure. This is important, because elsewhere on this site content with very different content structures gets mapped into the same presentation structure, subject to the same formatting rules, and thus it is possible for me to define a single rule-set that drives the middle layers of the production of all my content, a single page-layout that drives the outer layers, and appropriate extensions to which the sub-formatting of special-purpose inner blocks like tables and photosets can be delegated.

The usefulness of RSS, similarly, is largely due to the fact that it defines a common presentation structure into which dissimilar content structures may be mapped. Different feed sources may put semantically different and/or compound information into the title and description fields, but the writing software doesn't have to know or care about the formatting rules, and the reading software doesn't have to know or care about the content structure. The drawback of using presentation structure as an interchange medium, of course, is that the reading software can't get the original content structure even if it could do something interesting with it. Human readers can re-interpolate it, but for the machines RSS tends to be lossy.

This was also, maybe obviously, the original design concept for HTML: standardize a presentation structure that can then act as universal intermediary between content and screen. RSS gets away with its limitations because it's an alternate channel, but as the web emerged, HTML was the web, and universal intermediation quickly proved unsatisfying in both directions: writers couldn't exercise enough control over formatting when they needed or wanted to (and programmers often assume "want" is always the right word here, but publishers understand that publishing is different than just writing), and machines couldn't add enough processing insight without finer-grained and/or domain-specific data schema.

Here, then, are some of the elements of the new model I want, some of what, from twenty years of working with information in both publishing and software spheres (and this isn't what I thought after ten, so maybe it won't be what I think after forty, but is that because I change, or because the world does?), I believe the whole system needs in order to fulfill its potential as a medium at once for direct human communication and human understanding supplemented by computer reasoning:

- Not only should all meaningful content begin in its own schema, but this machine-parsable content structure should, inherently and automatically, underlie and accompany the human-visible presentation and formatting of all information. Imagine, if this were our only problem, adding an Elemental XML section to every HTML page, so that each page would carry its pre-presentation data in addition to all of its other markup, and splitting the View Source command into View Presentation Code and View Source Data to offer different tools for each. (Microformats are a similarly motivated effort, establishing presentation-structure conventions for particular kinds of content structure, but conflating the two kinds of structure is only reasonable as a short-term tactical compromise in a system where there's no good way to separate them, anyway.)

- The mapping of content structure into presentation structure must be so trivially easy, and such an obvious entry into a richly distributed universe of sophisticated standard lexicons and templates, that nobody will even be tempted to try to skip the step by pretending that their content doesn't have any other structure than its presentation. Imagine, as you're publishing something, that you could chose dynamically from not only your own repertoire of formats and the templates provided by your authoring software, but from a social universe of templates, of all granularities, available from anyone who has one to offer. The laborious specific control of your own formatting, or the flexible custom extension of your presentation structure, should be optional opportunities for the motivated, not required burdens of participation.

- The layout model should be based on recursive containment from the outside in (probably with layers, for graphic depth). Exceptional behavior, like violating margins, must be declared explicitly, not arise from routine errors in normal use. It should be trivial to map one element of presentation structure into one formatting container, to flow multiple elements of presentation structure into one formatting container, or to flow one or more elements of presentation structure through an arbitrarily linked series of formatting containers. We've learned a lot about UI and usability since Quark and PageMaker were invented, and not everything we ever wanted to do in books and magazines applies the same way on a screen or in an interactive environment, but in many ways the screen world is only now approaching the point where print was before computers, so as is already beginning to sink in about typography, more old lessons apply than not.

- Where the new medium has new abilities, our tools should be granting new powers to us, not demanding new chores. AJAX is a clever retrofit of what should have been a native idiom. Forget paging vs scrolling, Google Maps is how everything offscreen should work, the computers dealing with computer constraints like bandwidth and memory without bringing people into issues that don't concern people. And if content were encapsulated intelligently, it wouldn't take Flash or iframes or scripts to make a piece of a page do things a whole page can already do. The web is a bad application environment kludged onto a bad publishing environment, and it ought to be a composite environment in which publishers realize that sometimes they are publishing applications and experiences and devices, not just pictures and words.

- The separation of content, presentation structure and formatting is necessary for everyone's purposes, not just the auteurs and the programmers and the machines. Good, reusable, maintainable presentation design, even when it's done by dedicated designers, should always work first from presentation structure to formatting rules. The handcrafting of individual exceptions should be an elaboration on a framework of rules, not a repetitive substitute for making the effort to understand patterns. I see way too much CSS code that specifies individual pixel-unit fonts and margins and paddings for every single id-numbered div in an entire page (or, worse, for every id-numbered div in a whole set of pages, so that the style-sheet can be "reused" across all of them). Sometimes this is a result of having misused the (X)HTML to model the content structure, rather than the presentation structure, so that the formats and the selectors don't line up right, but I bet it's more often just laziness. It's always faster to add a pixel than to generalize a rule about why, but it takes an incredibly tiny number of exceptions to complicate a rule-set so irretrievably that it can only be modified by further exceptions. For all but the rarest purposes where chaos is the order, the fewer rules the better, and the square of the fewer exceptions the better.

But fine. No matter what you credit as partial precedence, ubiquitous electronic publishing and communication as social infrastructure are at best in their adolescence, and it's amazing we've gotten this far with these primitive tools. The willingnesses to restart and rebuild are in our character, just as surely as myopia and impatience are our curses. Generations are how we learn.

So yes, this means starting over, but the new ways, when they're right, are easier than the old ones, and we only shrink from them out of fear of change. In place of the current HTML/CSS information foundation we will have data (content structure), mapping (content structure to presentation structure), page layout (the containers through which the presentation structures flow) and formatting (typography, color, spacing, ornamentation and illustration within those containers). Any of these can be implied from defaults (set by the reader, writer or both), included by reference to external sources, included by recursion, included conditionally by context, or defined inline. Most of this will still be mediated by tools for most people, but the tools will be simpler and more powerful, and will let us focus more on what we're saying to each other, and less on how.

And since the new way delivers both the formatting and the semantics, this will be a practical revolution that actually subsumes a theoretical one, better human communication interleaved with better machine communication, and thus the foundation for both better shopping and the dream of the internet being something qualitatively more profound and transformative than shopping.

Hundred Reasons: Lullaby (from Shatterproof Is Not a Challenge) (1.7M mp3)

First up in my morning-commute shuffle, and apparently exactly today's mood. I discovered Hundred Reasons in a tour listing when they were opening for Idlewild, and they have remained in my affection long after I've given up on most of the shouty bands I recognize as generally similar. I think, as with Jimmy Eat World (and as songs begin in shuffle I have more than once confused the two), there is some essential core of sadness that makes even the most bellowing moments plaintive instead of merely loud.

There are demos of new stuff up on their site.

First up in my morning-commute shuffle, and apparently exactly today's mood. I discovered Hundred Reasons in a tour listing when they were opening for Idlewild, and they have remained in my affection long after I've given up on most of the shouty bands I recognize as generally similar. I think, as with Jimmy Eat World (and as songs begin in shuffle I have more than once confused the two), there is some essential core of sadness that makes even the most bellowing moments plaintive instead of merely loud.

There are demos of new stuff up on their site.

¶ Preparations for Opus 62b (Half-Symphony of First and Third Thoughts, or The Tempo of Sky) · 17 January 2006 essay/fiction/poem

C1: Remove all four strings, wind four (or five) layers of ordinary plastic wrap around the fingerboard, and re-string. Theocracies are inevitably undone by meteorology.

C5: Isolate this cellist stage left (see diagram), in a bidirectionally soundproof enclosure with visibility only towards the house. Performer should follow the score as normal, with timing cues from audience reaction. If you are sure of your own worth, you will be less reluctant to criticize others.

C8: Adjust to Morat tuning (modern) in movements 2 and 5. Never mistake hope for authority.

Va2: Performer should be contact-miked at the base of the throat (concealed under clothing if possible), and should whisper as indicated in the score. This channel should be mixed at the volume of the loudest single viola. America is not the only nation in which the market has failed God.

Va3: Perform standing, hooded. Air is the element that does not dream of airlessness.

1Vn2: Affix round mirror of 3" diameter to center rear of instrument body. The light is warmer here, but we feel tired and unsafe.

1Vn9: Each time an audience member coughs, stand and announce the next number (counting down from 50). After zero is reached, stop playing and stand for the remainder of the piece. If you interrupt a story, you assume responsibility for its conclusion.

2Vn3: Do not doubt yourself. You are born with wisdom, and lose it only through fear.

2Vn6: Insert nine glass marbles, as large as will fit through sound holes. Do not allow other people's envy to become your beacon.

2Vn7: Sit with bare feet in a tray of sand. Learn to say your name without speaking, without opening any doors.

FH1 & 3: Where marked in score, turn to face each other and join mouths of horns together. Charity is a distraction.

T2: Marching. Not forgetting the gift.

X1: Satellite radio. If music is not a language, then neither is Dutch.

X2: Manual typewriter (bell removed). Kind words are bought with foreign blood.

X3: Mild regret. There is no excuse for independence, but sometimes the alternatives take longer than lives.

X4: LG5275, ringers "Personal 2", "Personal 4" and "Young Cranes", volume "Medium High". The number should be listed in the program. Cities should be built by the children that will have to be born there.

X5: Shoe horn, dry soil. White is both the color of dust and the weight of famine.

Conductor: In addition to normal movements, a rook on an edge row or rank may turn at open corner squares and continue along the next rank or row. Circumnavigation is not why the Earth is round. "Round" is not what I mean, but math is the only real secret I have left.

Composer: The gap between morality and ethics is best understood as compassion. In the truest portraits, the voice of the brush is not the paint but the canvas.

Mezzanine right: Provide materials and instructions for paper airplanes to be thrown towards orchestra left. If you teach a baby to fly, she will leave the earth to us.

Orchestra center: One hour before show time, soak each seat cushion in warm honey. Keep to yourself. The nights are long and dense with lies.

Outer lobby: Line floor with pre-1986 magazine cigarette advertisements. Power is a metal, but forgiveness is a shape, patience is a hammer, and clarity is a vice.

Ladies toilet: Scented towels, but no running water. It doesn't matter what other people learn.

Front sidewalk: During intermission, oil and set alight. Unlike the sun, the moon must be invited, and sometimes we forget.

Nearest seacoast: Speak quietly to the water when there is nothing left to say.

Two weeks prior: Cancel, wait one hour, then retract the cancelation. It is good to grasp young that promises are made of skin.

Afterwards: All dissent is interred in the syntax of its assumptions. Only by moving outside of politics, formally, can one accurately articulate the constraints of historical inertia. Sumerian music utilized four extra keys we now deny. It is possible to make paper out of water and salt, but governments are at best compromises between expedience and flight. They tell us that all the new planets are equally flawed. Climates without seasons breed corruption among well-meaning idolators as readily as larvae among new-fallen fruit. Attach hinges with black tape. That is no longer the lowest note once we've thought of another. There was a town here, but then you came and told us the story of how the stars were brought to you and you clothed them in orange silk and perfect poetry, and our children left to follow their souls and our parents left to follow our children and now there is no home here but the way the air shifts to stay behind us when we fall upon our palms and our fables and the marble rises towards what our tongues were before we sold them to you for a dream of silence and the tempo of sky.

C5: Isolate this cellist stage left (see diagram), in a bidirectionally soundproof enclosure with visibility only towards the house. Performer should follow the score as normal, with timing cues from audience reaction. If you are sure of your own worth, you will be less reluctant to criticize others.

C8: Adjust to Morat tuning (modern) in movements 2 and 5. Never mistake hope for authority.

Va2: Performer should be contact-miked at the base of the throat (concealed under clothing if possible), and should whisper as indicated in the score. This channel should be mixed at the volume of the loudest single viola. America is not the only nation in which the market has failed God.

Va3: Perform standing, hooded. Air is the element that does not dream of airlessness.

1Vn2: Affix round mirror of 3" diameter to center rear of instrument body. The light is warmer here, but we feel tired and unsafe.

1Vn9: Each time an audience member coughs, stand and announce the next number (counting down from 50). After zero is reached, stop playing and stand for the remainder of the piece. If you interrupt a story, you assume responsibility for its conclusion.

2Vn3: Do not doubt yourself. You are born with wisdom, and lose it only through fear.

2Vn6: Insert nine glass marbles, as large as will fit through sound holes. Do not allow other people's envy to become your beacon.

2Vn7: Sit with bare feet in a tray of sand. Learn to say your name without speaking, without opening any doors.

FH1 & 3: Where marked in score, turn to face each other and join mouths of horns together. Charity is a distraction.

T2: Marching. Not forgetting the gift.

X1: Satellite radio. If music is not a language, then neither is Dutch.

X2: Manual typewriter (bell removed). Kind words are bought with foreign blood.

X3: Mild regret. There is no excuse for independence, but sometimes the alternatives take longer than lives.

X4: LG5275, ringers "Personal 2", "Personal 4" and "Young Cranes", volume "Medium High". The number should be listed in the program. Cities should be built by the children that will have to be born there.

X5: Shoe horn, dry soil. White is both the color of dust and the weight of famine.

Conductor: In addition to normal movements, a rook on an edge row or rank may turn at open corner squares and continue along the next rank or row. Circumnavigation is not why the Earth is round. "Round" is not what I mean, but math is the only real secret I have left.

Composer: The gap between morality and ethics is best understood as compassion. In the truest portraits, the voice of the brush is not the paint but the canvas.

Mezzanine right: Provide materials and instructions for paper airplanes to be thrown towards orchestra left. If you teach a baby to fly, she will leave the earth to us.

Orchestra center: One hour before show time, soak each seat cushion in warm honey. Keep to yourself. The nights are long and dense with lies.

Outer lobby: Line floor with pre-1986 magazine cigarette advertisements. Power is a metal, but forgiveness is a shape, patience is a hammer, and clarity is a vice.

Ladies toilet: Scented towels, but no running water. It doesn't matter what other people learn.

Front sidewalk: During intermission, oil and set alight. Unlike the sun, the moon must be invited, and sometimes we forget.

Nearest seacoast: Speak quietly to the water when there is nothing left to say.

Two weeks prior: Cancel, wait one hour, then retract the cancelation. It is good to grasp young that promises are made of skin.

Afterwards: All dissent is interred in the syntax of its assumptions. Only by moving outside of politics, formally, can one accurately articulate the constraints of historical inertia. Sumerian music utilized four extra keys we now deny. It is possible to make paper out of water and salt, but governments are at best compromises between expedience and flight. They tell us that all the new planets are equally flawed. Climates without seasons breed corruption among well-meaning idolators as readily as larvae among new-fallen fruit. Attach hinges with black tape. That is no longer the lowest note once we've thought of another. There was a town here, but then you came and told us the story of how the stars were brought to you and you clothed them in orange silk and perfect poetry, and our children left to follow their souls and our parents left to follow our children and now there is no home here but the way the air shifts to stay behind us when we fall upon our palms and our fables and the marble rises towards what our tongues were before we sold them to you for a dream of silence and the tempo of sky.

¶ 2005 in numbers · 16 January 2006

Here is how I did on my three explicitly stated quantitative metrics for calendar 2005:

Running

I hit my distance goal of 1000 miles in early December, and even with an injury-constrained final month finished the year with 1052 miles. My average pace across all conditions and routes was 7:24/mile, beating my internal target of 7:30. I also wanted to be able to comfortably run 6:30/mile on 5-mile training runs, but I can't yet, and maybe won't ever. I can get under 7:00 without straining, but anything below 6:50 is hard, and 6:30 requires race intensity. I meant to enter a 5k this year and try to finish it in less than 20:00, but I never got around to it, and didn't really feel bad about that.

Body Equilibrium

My weight spent the year, as intended, within a couple pounds of 132. It's been there for two years, so I'm no longer really worried that there's anything tenuous about the state, but I still monitor it fairly closely. The degree of close scrutiny I applied to my bite-by-bite consumption in 2005 varied, but Bethany and my ongoing attention to our shared shopping/cooking/eating patterns is almost certainly more directly positive and ultimately sustainable than any rules applied at the point of chewing.

Reading

Hoping to get through 50 books in 2005 was easily the least realistic of my numeric impulses, and projections showed me missing it up until very late in the year, but after an epic transit of the complete Baroque Cycle I actually ended the year at 52 books and 18,232 pages. Both of these are ten-year personal highs, and more than double the woeful (reading-wise) 2002 and 2003 (which were attributable, oddly, to almost opposite trends elsewhere in my life). More significantly, in 2005 I actually read more than I bought (and was given), and so began, after many years of seemingly uncheckable increase, to decrease my backlog of books waiting unread on my shelves.

These amounts of running and eating and reading all felt pretty good, so for 2006 I'm simply going to repeat all three goals, unaltered: run 1000 miles and maybe enter a couple races, gain or lose no weight, read 50 good books.The tempting thing to do with goals is always to increase them, but that's reliably at the expense of things that are harder to measure but more important to do.

Running

I hit my distance goal of 1000 miles in early December, and even with an injury-constrained final month finished the year with 1052 miles. My average pace across all conditions and routes was 7:24/mile, beating my internal target of 7:30. I also wanted to be able to comfortably run 6:30/mile on 5-mile training runs, but I can't yet, and maybe won't ever. I can get under 7:00 without straining, but anything below 6:50 is hard, and 6:30 requires race intensity. I meant to enter a 5k this year and try to finish it in less than 20:00, but I never got around to it, and didn't really feel bad about that.

Body Equilibrium

My weight spent the year, as intended, within a couple pounds of 132. It's been there for two years, so I'm no longer really worried that there's anything tenuous about the state, but I still monitor it fairly closely. The degree of close scrutiny I applied to my bite-by-bite consumption in 2005 varied, but Bethany and my ongoing attention to our shared shopping/cooking/eating patterns is almost certainly more directly positive and ultimately sustainable than any rules applied at the point of chewing.

Reading

Hoping to get through 50 books in 2005 was easily the least realistic of my numeric impulses, and projections showed me missing it up until very late in the year, but after an epic transit of the complete Baroque Cycle I actually ended the year at 52 books and 18,232 pages. Both of these are ten-year personal highs, and more than double the woeful (reading-wise) 2002 and 2003 (which were attributable, oddly, to almost opposite trends elsewhere in my life). More significantly, in 2005 I actually read more than I bought (and was given), and so began, after many years of seemingly uncheckable increase, to decrease my backlog of books waiting unread on my shelves.

These amounts of running and eating and reading all felt pretty good, so for 2006 I'm simply going to repeat all three goals, unaltered: run 1000 miles and maybe enter a couple races, gain or lose no weight, read 50 good books.The tempting thing to do with goals is always to increase them, but that's reliably at the expense of things that are harder to measure but more important to do.

¶ 2005 in movies · 15 January 2006

Here are ten I feel different for having seen:

1. Me and You and Everyone We Know

An intertwined miscellany of wounded adults and curious children try bedraggledly to break through their own and each others' patched-together shells. Undeniably precious, hyper-self-consciously eccentric, and to me unreasonably charming. Maybe the largest number of compellingly detailed characters ever packed into the least film time, and one of the rare movies in which even the characters with only one line usually get a good one.

2. 3-Iron (Bin-jip, Korea, 2004)

Catch-and-release identity theft as the ultimate solipsistic performance-art. Ethereally understated, for long stretches enthrallingly wordless, and about as empathetic and complex a portrait of long-resigned and suddenly-fractured loneliness as film probably allows.

3. Stay

A virtuoso weaving of the dream-logic associations of unraveling memory, and a case study in how few special effects you actually need if you know what people are really trying to remember or forget.

4. Hana & Alice (Hana to Arisu, Japan, 2004)

Friendship, love and growing up are universal in aggregate, but unique in each subjective experience, and thus one of the most enduring things art can aspire to do is show us what it might be like to have been anyone else.

5. Nobody Knows (Dare mo shiranai, Japan, 2004)

Four children, .04 parents, and no wishful magic.

6. The Curse of the Were-Rabbit

Even more old-fashioned in comic dignity than in animation technique.

7. A Very Long Engagement (Un long dimanche de fiançailles, France, 2004)

Amelie in wartime.

8. Millions

Spy Kids with cardboard boxes instead of spy toys, a bag of expiring money instead of a robot brain, and grown-ups with even fewer secret powers than the kids.

9. Krama mig! (Sweden via Montreal World Film Festival, 2005)

Maybe mundane life in a small town is only interesting if it's somebody else's town, but most towns are somebody else's.

10. Bright Future (Akarui mirai, Japan, 2003)

Debilitating nihilism, fluorescent jellyfish and fabulous pants.

I expect to also remember Batman Begins, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Finding Neverland, Good Night and Good Luck, Hauru no ugoku shiro (Howl's Moving Castle), Hotel Rwanda, Kung Fu Hustle and Super Size Me.

1. Me and You and Everyone We Know

An intertwined miscellany of wounded adults and curious children try bedraggledly to break through their own and each others' patched-together shells. Undeniably precious, hyper-self-consciously eccentric, and to me unreasonably charming. Maybe the largest number of compellingly detailed characters ever packed into the least film time, and one of the rare movies in which even the characters with only one line usually get a good one.

2. 3-Iron (Bin-jip, Korea, 2004)

Catch-and-release identity theft as the ultimate solipsistic performance-art. Ethereally understated, for long stretches enthrallingly wordless, and about as empathetic and complex a portrait of long-resigned and suddenly-fractured loneliness as film probably allows.

3. Stay

A virtuoso weaving of the dream-logic associations of unraveling memory, and a case study in how few special effects you actually need if you know what people are really trying to remember or forget.

4. Hana & Alice (Hana to Arisu, Japan, 2004)

Friendship, love and growing up are universal in aggregate, but unique in each subjective experience, and thus one of the most enduring things art can aspire to do is show us what it might be like to have been anyone else.

5. Nobody Knows (Dare mo shiranai, Japan, 2004)

Four children, .04 parents, and no wishful magic.

6. The Curse of the Were-Rabbit

Even more old-fashioned in comic dignity than in animation technique.

7. A Very Long Engagement (Un long dimanche de fiançailles, France, 2004)

Amelie in wartime.

8. Millions

Spy Kids with cardboard boxes instead of spy toys, a bag of expiring money instead of a robot brain, and grown-ups with even fewer secret powers than the kids.

9. Krama mig! (Sweden via Montreal World Film Festival, 2005)

Maybe mundane life in a small town is only interesting if it's somebody else's town, but most towns are somebody else's.

10. Bright Future (Akarui mirai, Japan, 2003)

Debilitating nihilism, fluorescent jellyfish and fabulous pants.

I expect to also remember Batman Begins, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Finding Neverland, Good Night and Good Luck, Hauru no ugoku shiro (Howl's Moving Castle), Hotel Rwanda, Kung Fu Hustle and Super Size Me.

¶ 2005 in music · 14 January 2006

The short version:

1. Kate Bush: Aerial & Tori Amos: The Beekeeper

2. Low: The Great Destroyer

3. Waltham: Waltham & Tommy heavenly6: Tommy heavenly6

4. Imogen Heap: Speak for Yourself

5. L'Arc~en~Ciel: AWAKE

6. Regina Spektor: Soviet Kitsch

7. Yokota Susumu: Symbol

8. Zapruder Point: It's Always the Quiet Ones & The Frames: Burn the Maps

9. Tullycraft: Disenchanted Hearts Unite

10. 50 Foot Wave: Golden Ocean

The long version:

The Best of 2005

1. Kate Bush: Aerial & Tori Amos: The Beekeeper

2. Low: The Great Destroyer

3. Waltham: Waltham & Tommy heavenly6: Tommy heavenly6

4. Imogen Heap: Speak for Yourself

5. L'Arc~en~Ciel: AWAKE

6. Regina Spektor: Soviet Kitsch

7. Yokota Susumu: Symbol

8. Zapruder Point: It's Always the Quiet Ones & The Frames: Burn the Maps

9. Tullycraft: Disenchanted Hearts Unite

10. 50 Foot Wave: Golden Ocean

The long version:

The Best of 2005

¶ 13 January 2006

"I fall in love to you", she sings, in one of the few easy Japanese/English false-cognate errors. Five out of six words are right, and I know exactly what she means, but we have spent these centuries inventing ways that anyone other's sincerities and truths, from even the most trivial distance, can always be safely invalidated.