25 August 2010 to 4 March 2010

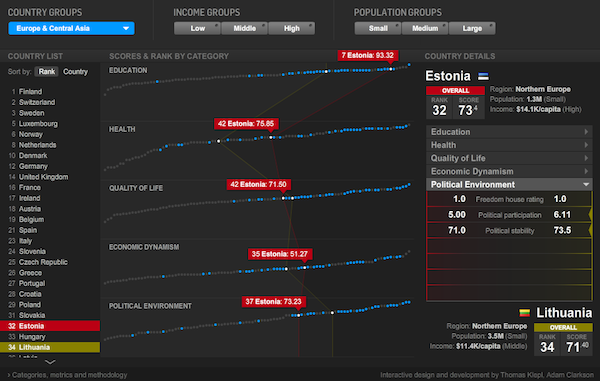

This Newsweek best-country infowidget is plainly cool. Run your mouse down the list of countries, top to bottom, and watch the waves ebb leftwards. Run it along any of the lines and see the spiky flow whip along the others. Pick subsets along the top and see dots light up across the lines. This is data sorcery, turning mute masses of numbers into effortless insight. Insight? Sight, anyway.

As a designer of generalized data-analysis tools, though, I'm almost invariably frustrated by these things. They look like magic, and I have lots of places where I want things to look like magic. But to look like magic, reliably, they actually have to work like machines. I want to be able to pour other data into this structure. I admire the heroism that went into solving this one specific information-display problem, but I don't want every new data-analysis task to always require new heroism. If you have to keep doing it over and over again, it's not heroic any more.

But when I start taking these things apart, so that I can figure out how to put them back together with other data inside, I discover altogether too much convenient "magic" where I need simple reliable gears and levers. Like:

- What happens if the lines in the middle aren't as flat as these, or there are more than five of them, or there are more than 100 data points, or the measurements aren't as correlated?

- In fact, there are more than 100 data points here, or at least there should be. If I were Burkina Faso, dangling at the end of those Education and Quality of Life lines, I'd be pretty angry. There are almost 100 more countries not shown here, all of which are by definition below them in overall score. There's a big difference between 100th out of 100 and 100th out of 200.

- Why can't I do other "regions", and why can't I filter combinations of region/income/population? And why do the filters go region/income/population, but the stats on the right go region/population/income? And what if I had 9 sets of categories instead of 3? And shouldn't there be maps somewhere?

- What if the measurements aren't all numbers (or aren't all single numbers)?

- And as cool as the waves and spikes look, are they actually the most informative information-design choice? They emphasize shapes, but since the five metrics are independent, these shapes are not actually meaningful per se.

- The wide aspect-ratio of the lines makes rank dramatically visible on the horizontal axis, but absolute value hard to visually assess on the vertical axis. The waves reinforce this further, especially if you select two countries to compare them. But isn't absolute value far more significant than rank on all of these measures?

- And what if I need to compare 3 things, instead of just 2? Or 9? Or 15?

- What if I want a different weighting of components in my overall score? What if I want a different weighting of subcomponents in my subscores? What if I want a different number of subscores, or different groupings? What if I want to add or remove measurements? How do I check if a dot is right? How do I examine what it means?

- What about latitude and longitude, or year of independence, or soccer rank, or internet usage, or libraries per capita, or coffee quality?

- Why did they reinvent the scroll bar? Never reinvent the scroll bar.

- Really. Never reinvent the scroll bar.

- If you're going to use color to show low/middle/high and small/medium/large, why bucket them? Why not show a continuum? Why not show sliders for filtering at arbitrary points?

- Not that sliders don't have their own UI issues, as they encourage visual outlier-clipping, which is rarely a statistically straightforward thing to do to data.

- Why does nothing here show any indication of precision or error, and what would happen to the display if it did?

- How would you use this if you were blind? Why doesn't it scale with the browser window?

- And how, even if we could answer all those questions, do you get any other set of data into this? How do you manage the data behind this? Where is "behind this"?

So yes, this is cool. I'm glad it exists. But I can't help feeling like this is not really the way we win the war against ignorance. We can't afford to solve every problem with this much specificity. And even this, I suspect, is a symptom: we get solutions with such specificity because there is such a poverty of solutions with generality. When there's no easy way, all the hard ways start sounding about the same.

And thus my own far less glamorous life with data: lists, tables, numbers, the occasional stripe of color. It won't let you makes waves and spikes out of your data, but then, neither will this. This thing won't let you do anything with your data. Something should.

¶ #5 · 1 July 2010

I left Lotus before the IBM acquisition, but my next employer, Ziff-Davis Interactive, was bought by AT&T (#1) and then resold to Nets, Inc. (#2) during my time there. After I resigned from Nets (delivering my resignation letter to, weirdly, the same CEO from whom I resigned at Lotus) I joined a startup called Instinctive Technology, which was subsequently renamed to eRoom Technology and later acquired by Documentum (#3), which was then itself acquired by EMC (#4). So every company for whom I've worked has been acquired during or shortly after my time there.

The pattern continues, according to today's announcement that my current employer, ITA Software, will be acquired by Google.

#5.

#1-4 were all good for me, personally, but bad for my projects. Hoping this one is half different...

[16 July addendum: my optimism got a huge boost today from the news that Metaweb is now part of Google, too!]

The pattern continues, according to today's announcement that my current employer, ITA Software, will be acquired by Google.

#5.

#1-4 were all good for me, personally, but bad for my projects. Hoping this one is half different...

[16 July addendum: my optimism got a huge boost today from the news that Metaweb is now part of Google, too!]

¶ RIP Ronnie James Dio · 16 May 2010

If you could have any living singer's voice, whose would it be?

I need a new answer now.

I need a new answer now.

The World Cup has a long, storied history. 708 matches across 18 tournaments, involving 80ish different countries, more than 5000 players, and more than 2000 goals. That's a lot of soccer.

It's not really that much data, though. Soccer isn't a sport for actuaries. My AAC file for Shakira's 2010 World Cup theme song is approximately three times the size of my data file containing more or less all salient info about the entire match-history of the Cup finals. When people talk about Big Data, this is not what they mean. This is Small Data.

Even Small Data can be hard to get right, though. Who scored the second Cuban goal in their 3-3 draw with Romania on 5 June 1938? I'm betting you don't quite remember the guy's name, either.

FIFA's official stats page for this match claims that the second Cuban goal was scored by Jose Magrina in the 69th minute. The listed Cuban lineup, however, includes no such player among either the starters or the substitutes.

Planet World Cup's version has the middle Cuban goal scored by "Maquina", who the FIFA lineup doesn't list either, and PWC doesn't have a lineup to reference. They also have the second Romanian goal coming after the second Cuban goal, not before.

Scoreshelf has a page for Carlos Maquina Oliveira, which matches FIFA's listing of Carlos Oliveira, so that's something. But Scoreshelf credits him with the second and third Cuban goals, and their match page has fairly different timings for all six goals, and credits the first Romanian goal to a different player.

InfoFootballOnline's 1938 stats page claims Maquina had 2 goals for Cuba, but it also claims Héctor Socorro had 3, including 2 of the 3 in the 3-3 draw, contradicting other sites' credit of one of the Cuban goals to Tomas Fernández.

The Wikipedia page for 1938 has yet another set of timings, and expresses its own creativity by giving the third Cuban goal to Juan Tuñas.

So I can say, with pretty good confidence, that I don't know who scored these goals, nor when they occurred. If you know of an explicably authoritative source for the goal credits for Cuba's 1938 World Cup games, send me the reference. But of all the versions, FIFA's official one is clearly and ironically the least sensible, as it involves a player that none of these sources, including FIFA themselves, list as having been in the game. Machines can't tell us how we're wrong, but they ought to be able to easily tell us when we're not making any sense.

So for my version of World Cup History in Needle, I've made my own decisions, too, but I can at least say, with computationally verified certainty, that they're internally consistent. Across this whole small sprawling history, there are no goals or cards attributed to unknown players, the itemized goal totals (including own-goals) match the official final scores, the computed champions match the record books. I've fixed dozens of games where FIFA's stats list starters being replaced by ghosts, or 12th players joining the fray. I found the two cases where players were carded while they weren't even in the game, and looked them up to make sure that's what actually happened. I've checked that there are no goals credited during overtime of games that didn't have any, I fixed the game that was listed as happening in February, and I fixed the extra errors my own non-soccer-specific software introduced (did you know that "NGA", the country-code for Nigeria, is also the Vietnamese word for Russia?).

It shouldn't have come to this. I'm an art major working for a company that makes airline software. Between FIFA and a dozen sports and news companies, somebody who lives by this data ought to have fixed it all years ago. The worst thing is, I suspect they've been trying. And yet, every source I checked had problems I could tell they couldn't find. When all data had to do was look right in the galley proofs, it was a publishing problem. But bringing publishing tools to data problems is like bringing a Strunk & White to a math fight.

It's not really that much data, though. Soccer isn't a sport for actuaries. My AAC file for Shakira's 2010 World Cup theme song is approximately three times the size of my data file containing more or less all salient info about the entire match-history of the Cup finals. When people talk about Big Data, this is not what they mean. This is Small Data.

Even Small Data can be hard to get right, though. Who scored the second Cuban goal in their 3-3 draw with Romania on 5 June 1938? I'm betting you don't quite remember the guy's name, either.

FIFA's official stats page for this match claims that the second Cuban goal was scored by Jose Magrina in the 69th minute. The listed Cuban lineup, however, includes no such player among either the starters or the substitutes.

Planet World Cup's version has the middle Cuban goal scored by "Maquina", who the FIFA lineup doesn't list either, and PWC doesn't have a lineup to reference. They also have the second Romanian goal coming after the second Cuban goal, not before.

Scoreshelf has a page for Carlos Maquina Oliveira, which matches FIFA's listing of Carlos Oliveira, so that's something. But Scoreshelf credits him with the second and third Cuban goals, and their match page has fairly different timings for all six goals, and credits the first Romanian goal to a different player.

InfoFootballOnline's 1938 stats page claims Maquina had 2 goals for Cuba, but it also claims Héctor Socorro had 3, including 2 of the 3 in the 3-3 draw, contradicting other sites' credit of one of the Cuban goals to Tomas Fernández.

The Wikipedia page for 1938 has yet another set of timings, and expresses its own creativity by giving the third Cuban goal to Juan Tuñas.

So I can say, with pretty good confidence, that I don't know who scored these goals, nor when they occurred. If you know of an explicably authoritative source for the goal credits for Cuba's 1938 World Cup games, send me the reference. But of all the versions, FIFA's official one is clearly and ironically the least sensible, as it involves a player that none of these sources, including FIFA themselves, list as having been in the game. Machines can't tell us how we're wrong, but they ought to be able to easily tell us when we're not making any sense.

So for my version of World Cup History in Needle, I've made my own decisions, too, but I can at least say, with computationally verified certainty, that they're internally consistent. Across this whole small sprawling history, there are no goals or cards attributed to unknown players, the itemized goal totals (including own-goals) match the official final scores, the computed champions match the record books. I've fixed dozens of games where FIFA's stats list starters being replaced by ghosts, or 12th players joining the fray. I found the two cases where players were carded while they weren't even in the game, and looked them up to make sure that's what actually happened. I've checked that there are no goals credited during overtime of games that didn't have any, I fixed the game that was listed as happening in February, and I fixed the extra errors my own non-soccer-specific software introduced (did you know that "NGA", the country-code for Nigeria, is also the Vietnamese word for Russia?).

It shouldn't have come to this. I'm an art major working for a company that makes airline software. Between FIFA and a dozen sports and news companies, somebody who lives by this data ought to have fixed it all years ago. The worst thing is, I suspect they've been trying. And yet, every source I checked had problems I could tell they couldn't find. When all data had to do was look right in the galley proofs, it was a publishing problem. But bringing publishing tools to data problems is like bringing a Strunk & White to a math fight.

¶ Pain Brings Us Together · 12 May 2010

¶ Happy Notes, Obsessive Numbers · 12 May 2010 listen/tech

I was doing some more analysis on Encyclopaedia Metallum data, as I seem to end up doing one way or another most weeks, and it occurred to me to add in country populations so I could do bands per capita. This is not a rigorous statistic, since for some regions of the world it probably says more about the EM contributor-base than it does about the actual distributions of musicians, but the top of the list was pretty striking:

1. Finland - 471 bands per million people

2. Sweden - 330

3. Norway - 239

4. Iceland - 189

5. Denmark - 113

Yes, I have rediscovered the existence of Scandinavia statistically!

For comparison:

28. United States - 49

29. United Kingdom - 46

And way down at the very end (among countries with at least 10 bands, at any rate):

87. China - 0.097

88. India - 0.068

There are a fair number of places that have, as far as EM knows, no metal bands at all, but I've got all the populations in place, so if anybody starts a band on Pitcairn or Wallis et Futuna next week, I'm ready.

(Interesting, too, that Finland leads the world in both metal bands and Winter Olympic medals per capita.)

(In the interest of accuracy, I should note that if you include all countries, Liechtenstein actually comes in third with 251 bands per million people (by which we mean 9 bands for ~36,000 people). Liechtenstein is one of only two countries in the world where there are more Gothic Metal bands than any other style. The other place is Kuwait, where Gothic Metal bands outnumber all other styles, put together, by a commanding margin of 1 to 0. The band is called Nocturna.)

1. Finland - 471 bands per million people

2. Sweden - 330

3. Norway - 239

4. Iceland - 189

5. Denmark - 113

Yes, I have rediscovered the existence of Scandinavia statistically!

For comparison:

28. United States - 49

29. United Kingdom - 46

And way down at the very end (among countries with at least 10 bands, at any rate):

87. China - 0.097

88. India - 0.068

There are a fair number of places that have, as far as EM knows, no metal bands at all, but I've got all the populations in place, so if anybody starts a band on Pitcairn or Wallis et Futuna next week, I'm ready.

(Interesting, too, that Finland leads the world in both metal bands and Winter Olympic medals per capita.)

(In the interest of accuracy, I should note that if you include all countries, Liechtenstein actually comes in third with 251 bands per million people (by which we mean 9 bands for ~36,000 people). Liechtenstein is one of only two countries in the world where there are more Gothic Metal bands than any other style. The other place is Kuwait, where Gothic Metal bands outnumber all other styles, put together, by a commanding margin of 1 to 0. The band is called Nocturna.)

My week to pick three albums for the new ILX Metal Listening Club. Like a book club, but for metal albums. All are welcome to join us in contemplation of Fates Warning's Parallels, Cradle of Filth's Nymphetamine and HIM's Screamworks: Love in Theory and Practice.

I have a post on my work-blog about why geeky-sounding data-modeling issues matter to even simple-looking data.

The post uses some Oscar-award data as an example, as I just put together a Needle version of Oscar History, so if you ever wanted to be able to answer some obscure statistical question about the Oscars, now you can. (Or you can ask me, and I can...)

The post uses some Oscar-award data as an example, as I just put together a Needle version of Oscar History, so if you ever wanted to be able to answer some obscure statistical question about the Oscars, now you can. (Or you can ask me, and I can...)

From Revisiting HTTP based Linked Data:

If there's anybody in the universe (who isn't already a Semantic Web expert) who reads that and thinks "Yes! I gotta get one of those!", I'd be very surprised.

For that matter, if there's anybody in the data business, other than the writer, who reads that and thinks "Yes! That's the Grand Quest to which I have given my Life and Loyalty!", I'd be almost as surprised, and rather suspicious.

Contrast this:

I'm not saying this is the same level as "We hold these truths to be self-evident...", or "I'm not going to pay a lot for this muffler", either. It's a technical appeal, not a Radio Free Earth broadcast. But it's closer to comprehensible, at least, isn't it?

What is Linked Data?

"Data Access by Reference" mechanism for Data Objects (or Entities) on HTTP networks. It enables you to Identify a Data Object and Access its structured Data Representation via a single Generic HTTP scheme based Identifier (HTTP URI). Data Object representation formats may vary; but in all cases, they are hypermedia oriented, fully structured, and negotiable within the context of a client-server message exchange.

If there's anybody in the universe (who isn't already a Semantic Web expert) who reads that and thinks "Yes! I gotta get one of those!", I'd be very surprised.

For that matter, if there's anybody in the data business, other than the writer, who reads that and thinks "Yes! That's the Grand Quest to which I have given my Life and Loyalty!", I'd be almost as surprised, and rather suspicious.

Contrast this:

What is Whole Data?

Whole Data is a method of storing and representing your data so that you can explore it as easily as you browse the web, and examine or analyze it from any perspective at any time. It gives you and the computer a common language for talking about your data, so that the computer can answer your questions by examining your data the way you would, but way faster.

I'm not saying this is the same level as "We hold these truths to be self-evident...", or "I'm not going to pay a lot for this muffler", either. It's a technical appeal, not a Radio Free Earth broadcast. But it's closer to comprehensible, at least, isn't it?