20 July 2014 to 2 May 2014

¶ Play What You Say · 20 July 2014 listen/tech

Sometimes in blog posts I mention songs. Like Clockwise's "War Story Part One", which is really good. You should listen to it, seriously.

In fact, I would like to help you listen to it, not least because there's really no reason you should listen to it just because I say so, so listening to it better be really easy.

The fancy way would be to go find the track on Spotify, right-click it and pick "Copy Embed Code", and then paste that code into my HTML to get this embedded Play button.

That's pretty nice.

But sometimes I'm just mentioning a song in passing, or in some particular formatting like a table with other stuff, and the fancy embedded thing isn't what I want. It would be nice to also have a lower-overhead way to just mark a song-reference in text as a song-reference, and let some music-intelligence thing somewhere figure out how to actually find and play it.

So I made a first version of such a thing. It's pretty crude, in that you have to know about editing HTML, and be in an environment where you're allowed to. And it just plays a :30 sample, it doesn't log you in and play the whole song. But the HTML itself, at least, is very simple. So if you have a need for which those are acceptable conditions, and you want to try it, here's how it works.

First, add these two lines to the HEAD of your page:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://everynoise.com/spotplay.css" type="text/css">

<script type="text/javascript" src="https://everynoise.com/spotplay.js"></script>

And then just write your song-reference inside a span with the class "play", like this:

<span class=play>Andy Clockwise "War Story Part One"</span>

which produces this (click it once to play the excerpt, click again to stop it):

Andy Clockwise "War Story Part One"

When you play an excerpt, a little musical-note link also gets magically inserted, which you can use to go hear the whole song on Spotify if you want.

You can also refer to things in the possessive form Artist's "Song", like <span class=play>Big Deal's "Always Boys"</span> to produce Big Deal's "Always Boys", or the reverse-credit form "Song" by Artist, like <span class=play>"Dangerous Days" by Zola Jesus</span> to produce "Dangerous Days" by Zola Jesus, and it should be able to figure out what you mean. If you want to attach the reference to some visible text other than the artist and song-name, you can put the actual reference info in the tag, like this, where the code for that linked "this" is:

<span class=play artist="Broods" track="L.A.F">this</span>

and if for some reason you happen to have the Spotify URI for a particular track and would rather be precise about it, you can do this, where the code for that linked "this" is:

<span class=play trackid="spotify:track:6Qb82IcaWAB9ABeTyuzsV0">this</span>

Also, if for some reason you really don't want the Spotify link to be inserted, you can add "nolink=true" to your span to disable that feature, like this:

<span class=play nolink=true>Whitebear "Transmute / Release"</span>

which produces this (click to see the begrudging absence of magic):

Whitebear "Transmute / Release"

That's all I've got so far. If you try it, please let me know if it works for you, in either the functional or appealing senses. I'll be here thrashing around to "Snake Jaw" by White Lung.

(This all works by using the extremely excellent new Spotify Web API to look up songs and play excerpts.)

1 December 2015, three updates:

1: If you have a large page and want things to be playable before the whole page finishes loading, you can attach the onclick handlers yourself instead of waiting for them to be attached automatically. Just add onclick="playmeta(this)" to the same elements you marked with class=play.

2: If a track doesn't have a preview, for some reason, the code will set the attribute "unplayable" on your target element to be true. You can style this with CSS if you wish. For example, this makes linked images invert if their attached tracks are unplayable:

.play[unplayable] img {-webkit-filter: invert(1); filter: invert(1)}

3: If you want to refer to an album, instead of an individual track, you can add "albumid=spotify:album:wHaTeVeR" to your element. Like this:

<span class=play albumid=spotify:album:3yIcTZZOUsgq1xlkmtxnp6>Aedliga: The Format of the Air</span>

A representative track from the album will be chosen automatically by extremely sophisticated and complex logic, by which I mean that it will pick the first track unless the first track is very short and the second track isn't, or the first track has "Intro" in the title, in either of which cases it will pick the second track. Fancy.

In fact, I would like to help you listen to it, not least because there's really no reason you should listen to it just because I say so, so listening to it better be really easy.

The fancy way would be to go find the track on Spotify, right-click it and pick "Copy Embed Code", and then paste that code into my HTML to get this embedded Play button.

That's pretty nice.

But sometimes I'm just mentioning a song in passing, or in some particular formatting like a table with other stuff, and the fancy embedded thing isn't what I want. It would be nice to also have a lower-overhead way to just mark a song-reference in text as a song-reference, and let some music-intelligence thing somewhere figure out how to actually find and play it.

So I made a first version of such a thing. It's pretty crude, in that you have to know about editing HTML, and be in an environment where you're allowed to. And it just plays a :30 sample, it doesn't log you in and play the whole song. But the HTML itself, at least, is very simple. So if you have a need for which those are acceptable conditions, and you want to try it, here's how it works.

First, add these two lines to the HEAD of your page:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://everynoise.com/spotplay.css" type="text/css">

<script type="text/javascript" src="https://everynoise.com/spotplay.js"></script>

And then just write your song-reference inside a span with the class "play", like this:

<span class=play>Andy Clockwise "War Story Part One"</span>

which produces this (click it once to play the excerpt, click again to stop it):

Andy Clockwise "War Story Part One"

When you play an excerpt, a little musical-note link also gets magically inserted, which you can use to go hear the whole song on Spotify if you want.

You can also refer to things in the possessive form Artist's "Song", like <span class=play>Big Deal's "Always Boys"</span> to produce Big Deal's "Always Boys", or the reverse-credit form "Song" by Artist, like <span class=play>"Dangerous Days" by Zola Jesus</span> to produce "Dangerous Days" by Zola Jesus, and it should be able to figure out what you mean. If you want to attach the reference to some visible text other than the artist and song-name, you can put the actual reference info in the tag, like this, where the code for that linked "this" is:

<span class=play artist="Broods" track="L.A.F">this</span>

and if for some reason you happen to have the Spotify URI for a particular track and would rather be precise about it, you can do this, where the code for that linked "this" is:

<span class=play trackid="spotify:track:6Qb82IcaWAB9ABeTyuzsV0">this</span>

Also, if for some reason you really don't want the Spotify link to be inserted, you can add "nolink=true" to your span to disable that feature, like this:

<span class=play nolink=true>Whitebear "Transmute / Release"</span>

which produces this (click to see the begrudging absence of magic):

Whitebear "Transmute / Release"

That's all I've got so far. If you try it, please let me know if it works for you, in either the functional or appealing senses. I'll be here thrashing around to "Snake Jaw" by White Lung.

(This all works by using the extremely excellent new Spotify Web API to look up songs and play excerpts.)

1 December 2015, three updates:

1: If you have a large page and want things to be playable before the whole page finishes loading, you can attach the onclick handlers yourself instead of waiting for them to be attached automatically. Just add onclick="playmeta(this)" to the same elements you marked with class=play.

2: If a track doesn't have a preview, for some reason, the code will set the attribute "unplayable" on your target element to be true. You can style this with CSS if you wish. For example, this makes linked images invert if their attached tracks are unplayable:

.play[unplayable] img {-webkit-filter: invert(1); filter: invert(1)}

3: If you want to refer to an album, instead of an individual track, you can add "albumid=spotify:album:wHaTeVeR" to your element. Like this:

<span class=play albumid=spotify:album:3yIcTZZOUsgq1xlkmtxnp6>Aedliga: The Format of the Air</span>

A representative track from the album will be chosen automatically by extremely sophisticated and complex logic, by which I mean that it will pick the first track unless the first track is very short and the second track isn't, or the first track has "Intro" in the title, in either of which cases it will pick the second track. Fancy.

¶ We Are Electric, Energized and New · 19 July 2014 listen/tech

This morning I was listening to the Madden Brothers' "We Are Done", which came up on The Echo Nest Discovery list this week. I have the sinking/tingling feeling, and we'll see if I'm right because this isn't necessarily one of my actual talents, that this song is going to become ubiquitous enough in my environment that I'll look back wistfully on listening to it entirely voluntarily.

But listening to it also made me think about Fun's "We Are Young" and Pitbull and JLo's World Cup song "We Are One" and Taylor Swift's "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together". We are, we are, we are, we are. This kind of pointless internal word-association used to dissipate harmlessly inside my head. But now I have the resources to indulge it at scale.

So I made a Spotify playlist of 100 songs that follow the title-pattern "We Are [something]". And then I realized there were more of them, so I made a playlist of 1000 of them. And having done that, it was trivial to make similar playlists for "I Am [something]", You Are [something]", "He Is [something]", "She Is [something]" and "They Are [something]", so I did that, too. And then I have a thing that will summarize the contents of a playlist in various ways, so I ran it on these because why not?

The first thing one finds is that I, You and We songs are way more prevalent than She and They songs. And although there are plenty of He songs, they are disconcertingly overwhelmingly religious, which is kind of different. So I kept the He/She/They playlists for your amusement, but I only analyzed I, You and We.

Here's what The Echo Nest's listening machines report:

The I/You/We scores here are average values across the 1000 songs for each title pattern. Most Echo Nest metrics are normalized to be a unit-less decimal value between 0 and 1. Loudness is customarily measured on a weird negative scale, Tempo is in beats-per-minute, and Year is obviously in years.

The Power column measures the discriminatory power of each metric. So the two metrics that discriminate best between these three sets of songs are Acousticness and Energy. The metrics with the least power to discriminate between these sets are Valence (emotional mood), Bounciness (atmospheric density vs spiky jumpiness) and Danceability, all of which vary much more widely within each category than between them. Comparing the whole set to my earlier measurements of genre, year, popularity and country shows that the pronoun sets are about as distinct as sets based on country of origin, and more distinct than sets based on popularity, but less distinct on the whole than sets based on year or genre.

Which is a lot more difference than I expected, actually, particularly between You and We. Individual songs can have any individual character, but taken as an aggregate, "You Are" songs are significantly calmer, more acoustic and more organic in their rhythm. "We Are" songs are more energetic, more electric, notably more mechanically driven, and louder. That is, we sing more tender songs to each other, and more anthems about ourselves together.

We also seem to be singing more We Are songs lately. Or, to be more precise, because these 1000-song subsets are selected by popularity, more-recent We Are songs are a little more popular now in the aggregate. Attentive observers may recall that my earlier study showed correlations between time and both Acousticness and Energy over the years from 1950 to 2013. But both song-sets here are largely more-recent songs from well after the period of greatest historical change for either metric, and the magnitude of difference is significantly larger than the degree of variation predicted by year alone.

The I Am songs fall into an interestingly conflicted middle ground. They are more acoustic and less energetic than the rousing We Are anthems, but not as tender and sensitive as the wistful You Are odes. But while the I Am songs are closer to the You Are songs in rhythmic regularity, they're closer to the We Are songs in tempo.

So while you might reasonably expect We to be a compromise between I and You, this brief study clearly and crushingly demonstrates that the pre-computational centuries of the study of the psychology of self have been a sad speculative waste of time. Music and math prove that our individual selves float suspended between what we project onto others and what we dream that we could achieve together.

But listening to it also made me think about Fun's "We Are Young" and Pitbull and JLo's World Cup song "We Are One" and Taylor Swift's "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together". We are, we are, we are, we are. This kind of pointless internal word-association used to dissipate harmlessly inside my head. But now I have the resources to indulge it at scale.

So I made a Spotify playlist of 100 songs that follow the title-pattern "We Are [something]". And then I realized there were more of them, so I made a playlist of 1000 of them. And having done that, it was trivial to make similar playlists for "I Am [something]", You Are [something]", "He Is [something]", "She Is [something]" and "They Are [something]", so I did that, too. And then I have a thing that will summarize the contents of a playlist in various ways, so I ran it on these because why not?

The first thing one finds is that I, You and We songs are way more prevalent than She and They songs. And although there are plenty of He songs, they are disconcertingly overwhelmingly religious, which is kind of different. So I kept the He/She/They playlists for your amusement, but I only analyzed I, You and We.

Here's what The Echo Nest's listening machines report:

| Metric | I Am... | You Are... | We Are... | Power |

| Acousticness | 0.260 | 0.383 | 0.182 | 0.318 |

| Bounciness | 0.398 | 0.412 | 0.411 | 0.041 |

| Danceability | 0.498 | 0.508 | 0.524 | 0.077 |

| Energy | 0.649 | 0.541 | 0.705 | 0.333 |

| Instrumentalness | 0.196 | 0.171 | 0.235 | 0.099 |

| Loudness | -8.47 | -9.58 | -7.91 | 0.198 |

| Mechanism | 0.494 | 0.481 | 0.592 | 0.238 |

| Organism | 0.436 | 0.486 | 0.346 | 0.294 |

| Tempo | 124.0 | 118.1 | 125.6 | 0.137 |

| Valence | 0.424 | 0.421 | 0.421 | 0.007 |

| Year | 2004.4 | 2003.2 | 2007.1 | 0.201 |

The I/You/We scores here are average values across the 1000 songs for each title pattern. Most Echo Nest metrics are normalized to be a unit-less decimal value between 0 and 1. Loudness is customarily measured on a weird negative scale, Tempo is in beats-per-minute, and Year is obviously in years.

The Power column measures the discriminatory power of each metric. So the two metrics that discriminate best between these three sets of songs are Acousticness and Energy. The metrics with the least power to discriminate between these sets are Valence (emotional mood), Bounciness (atmospheric density vs spiky jumpiness) and Danceability, all of which vary much more widely within each category than between them. Comparing the whole set to my earlier measurements of genre, year, popularity and country shows that the pronoun sets are about as distinct as sets based on country of origin, and more distinct than sets based on popularity, but less distinct on the whole than sets based on year or genre.

Which is a lot more difference than I expected, actually, particularly between You and We. Individual songs can have any individual character, but taken as an aggregate, "You Are" songs are significantly calmer, more acoustic and more organic in their rhythm. "We Are" songs are more energetic, more electric, notably more mechanically driven, and louder. That is, we sing more tender songs to each other, and more anthems about ourselves together.

We also seem to be singing more We Are songs lately. Or, to be more precise, because these 1000-song subsets are selected by popularity, more-recent We Are songs are a little more popular now in the aggregate. Attentive observers may recall that my earlier study showed correlations between time and both Acousticness and Energy over the years from 1950 to 2013. But both song-sets here are largely more-recent songs from well after the period of greatest historical change for either metric, and the magnitude of difference is significantly larger than the degree of variation predicted by year alone.

The I Am songs fall into an interestingly conflicted middle ground. They are more acoustic and less energetic than the rousing We Are anthems, but not as tender and sensitive as the wistful You Are odes. But while the I Am songs are closer to the You Are songs in rhythmic regularity, they're closer to the We Are songs in tempo.

So while you might reasonably expect We to be a compromise between I and You, this brief study clearly and crushingly demonstrates that the pre-computational centuries of the study of the psychology of self have been a sad speculative waste of time. Music and math prove that our individual selves float suspended between what we project onto others and what we dream that we could achieve together.

¶ empath playlists · 15 July 2014 listen/tech

The empath charts for best albums by year, style and country now have linked Spotify playlists to go with each year/style/country.

Which means, among other things, that there's now this playlist of songs from the current best metal albums of 2014, as rated by Encyclopaedia Metallum reviewers via my peculiar math:

Or, at the less-dynamic end of the spectrum, songs from the best metal albums from the Faroe Islands, a list I monitor assiduously in case it ever gets a band other than Tyr.

Which means, among other things, that there's now this playlist of songs from the current best metal albums of 2014, as rated by Encyclopaedia Metallum reviewers via my peculiar math:

Or, at the less-dynamic end of the spectrum, songs from the best metal albums from the Faroe Islands, a list I monitor assiduously in case it ever gets a band other than Tyr.

I really like the new album by this Dutch band BLØF, and the Dutch are in the World Cup, so naturally I made a playlist with one song from each of the 32 countries in the finals. The songs were chosen capriciously by me, and span a variety of styles.

I would love to say that I just happened to know good recent songs I liked from all 32 of these countries, but that was not true. There were 15 of those, and 4 more where I knew the artist already but not the song. The other 13 I have dug up specifically for this occasion.

If you want a puzzle, in addition to some songs, you can try to figure out which song goes with which country, and then see if you can discern why they're in this particular order. I'm not saying you should do this. Probably better to just listen to the songs.

[Update: to keep this fun going, I am adding another song from each country that advances to another round, so with the round of 16 complete this is up to 56 songs, all of which are interesting and most of which I bet you have not heard.]

I would love to say that I just happened to know good recent songs I liked from all 32 of these countries, but that was not true. There were 15 of those, and 4 more where I knew the artist already but not the song. The other 13 I have dug up specifically for this occasion.

If you want a puzzle, in addition to some songs, you can try to figure out which song goes with which country, and then see if you can discern why they're in this particular order. I'm not saying you should do this. Probably better to just listen to the songs.

[Update: to keep this fun going, I am adding another song from each country that advances to another round, so with the round of 16 complete this is up to 56 songs, all of which are interesting and most of which I bet you have not heard.]

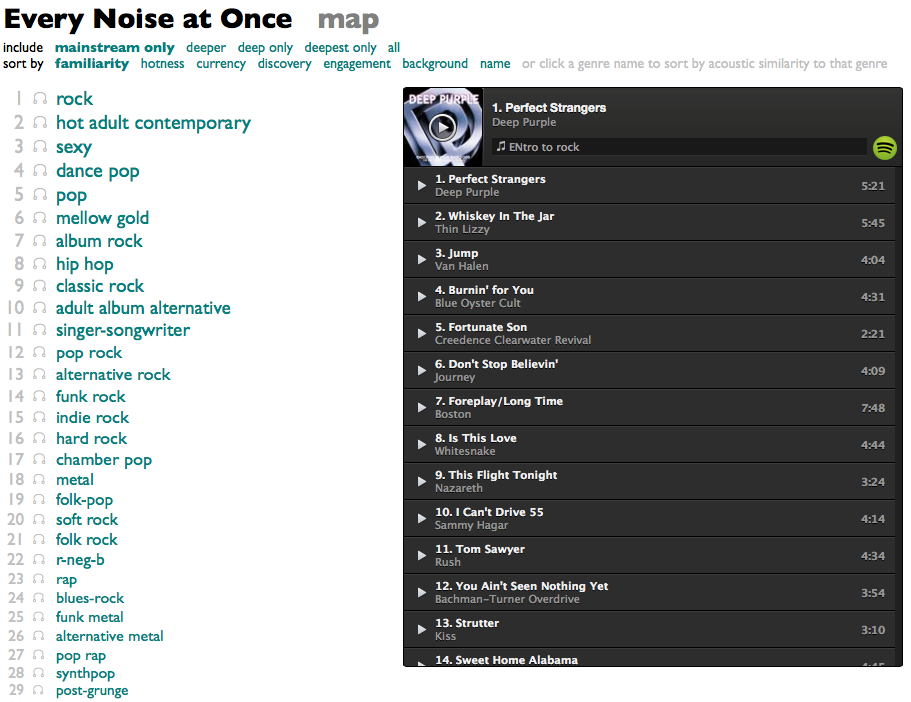

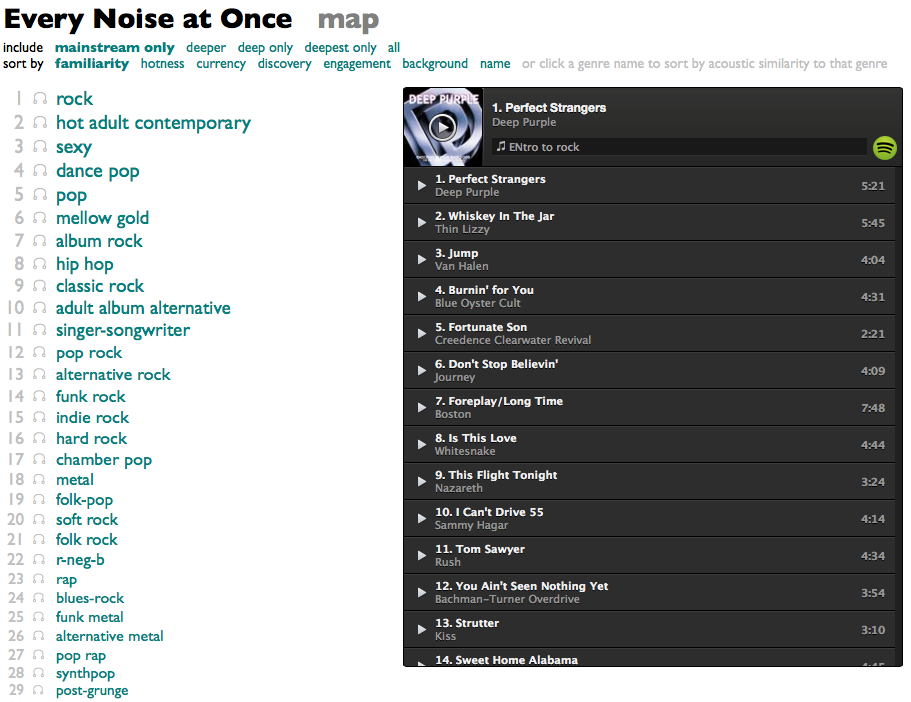

¶ Every Noise at Once on Spotify · 20 June 2014 listen/tech

To celebrate the release of the slick new Spotify Web API, I've converted Every Noise at Once to use the :30 preview clips provided by the new API.

Examples ought to now start playing quite a bit more promptly when you click them, there are examples available for more artists in the individual genre maps, and the whole thing ought to work in some parts of the world where it previously didn't.

The wistful flipside of this transition is that the map no longer uses or links to Rdio for anything. I remain very fond of Rdio, and they were great Echo Nest partners and enthusiastic supporters of this whole genre project from the beginning. But given the Echo Nest's acquisition by Spotify, Rdio's decision to stop using our services is, at least in business terms, unsurprising. And thus, conversely, I won't be producing or updating genre playlists on Rdio any more. New things (and there will be lots of new things) will now all happen on Spotify. Come on over.

Examples ought to now start playing quite a bit more promptly when you click them, there are examples available for more artists in the individual genre maps, and the whole thing ought to work in some parts of the world where it previously didn't.

The wistful flipside of this transition is that the map no longer uses or links to Rdio for anything. I remain very fond of Rdio, and they were great Echo Nest partners and enthusiastic supporters of this whole genre project from the beginning. But given the Echo Nest's acquisition by Spotify, Rdio's decision to stop using our services is, at least in business terms, unsurprising. And thus, conversely, I won't be producing or updating genre playlists on Rdio any more. New things (and there will be lots of new things) will now all happen on Spotify. Come on over.

I really can't sleep sitting up. But I can write songs on planes. It's a trade-off.

So here. This is my new song, composed and played on the flight from Boston to Keflavik, and sung in my Stockholm hotel room a few hours later as I fought to stay awake until a reasonable bedtime.

Methods Out of Favor (4:10)

All my songs kind of sound a little bit the same, which I'm OK with, but this one is at least in a slightly different tempo.

So here. This is my new song, composed and played on the flight from Boston to Keflavik, and sung in my Stockholm hotel room a few hours later as I fought to stay awake until a reasonable bedtime.

Methods Out of Favor (4:10)

All my songs kind of sound a little bit the same, which I'm OK with, but this one is at least in a slightly different tempo.

¶ A little more press · 21 May 2014 listen/tech

A couple new bits of press about Every Noise at Once:

PolicyMic - Discover Incredible New Music You've Never Heard Using This Interactive Map

Daily Dot - Dive into Every Noise at Once, a musical map of genres you didn't know existed

The first one is particularly good in the sense of being written thoughtfully by somebody other than me. The second one is particularly good in the sense of consisting largely of quotes from my answers to their questions.

PolicyMic - Discover Incredible New Music You've Never Heard Using This Interactive Map

Daily Dot - Dive into Every Noise at Once, a musical map of genres you didn't know existed

The first one is particularly good in the sense of being written thoughtfully by somebody other than me. The second one is particularly good in the sense of consisting largely of quotes from my answers to their questions.

¶ Every Noise at Once, more oncely · 20 May 2014 listen/tech

The Every Noise at Once genre-map reduces 13 music-analytical dimensions to 2 visual dimensions.

But if that's still a little too much for you, I've now added a version that reduces the whole genre space to one dimension: a list. But a list that you can sort and filter several different ways!

If one dimension is still too profuse and rococo for you, the reduction of the analytical space into zero dimensions is kind of this:

But if that's still a little too much for you, I've now added a version that reduces the whole genre space to one dimension: a list. But a list that you can sort and filter several different ways!

If one dimension is still too profuse and rococo for you, the reduction of the analytical space into zero dimensions is kind of this:

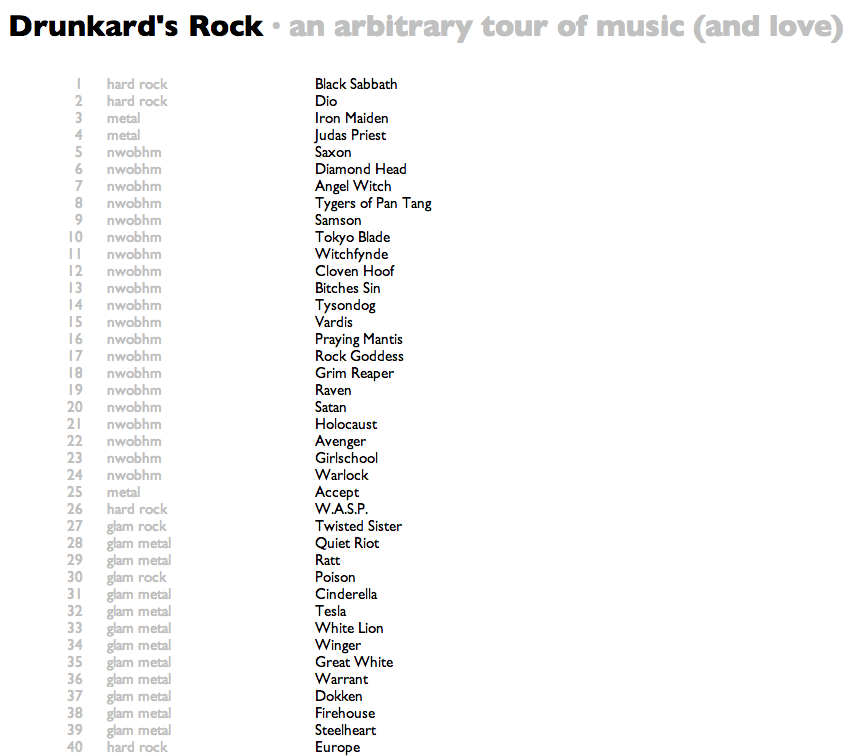

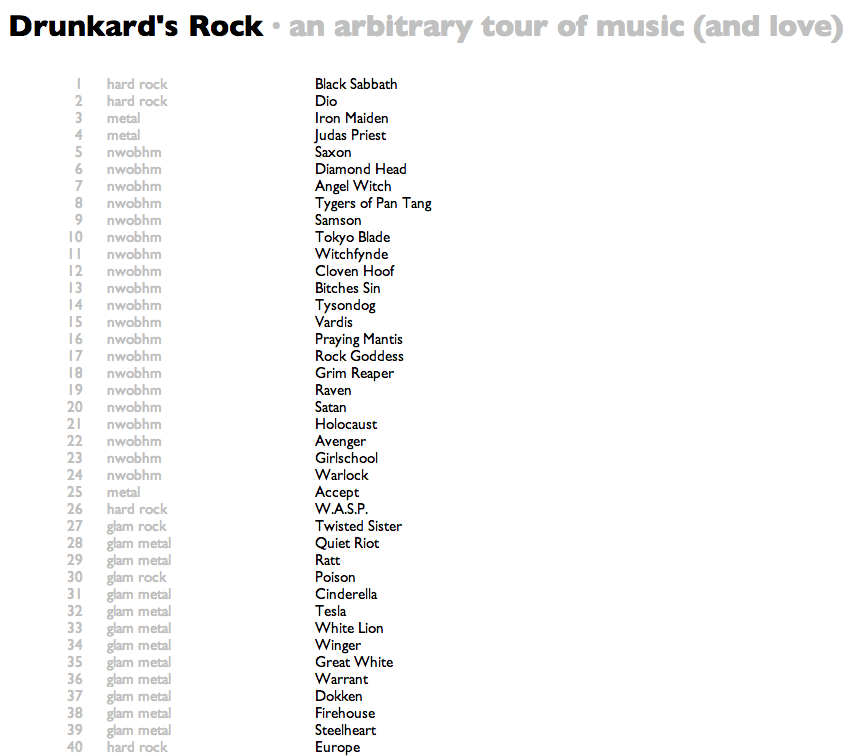

¶ Drunkard's Rock · 19 May 2014 listen/tech

Drunkard's Walk is a mathematical idea involving a random iterative traversal of a multidimensional space.

Drunkard's Rock is an experiment I did to pursue a random iterative traversal of the multidimensional musical artist-similarity space.

In the mathematical version, the drunkard is allowed to retrace their steps, and in fact the point of the problem is to determine the chance of the drunkard randomly arriving home again.

In my version, retracing steps is explicitly disallowed, and thus the drunkard is doomed to wander until the universe expires. Probably it says something about my personality that this seems like the preferable curse to me.

Anyway, I started the calculation with Black Sabbath, both because my own musical evolution sort of started in earnest with Black Sabbath, and because Paul Lamere used Black Sabbath as the reference point in his inversely minded Six Degrees of Black Sabbath, which attempts to find the shortest path between two bands.

My version, to reiterate, just keeps wandering. I guess it is searching for the longest path between Black Sabbath and whatever it finds last. Except I stopped it at 100k steps, because the resulting web page is enormous enough. It will annoy you least if you just leave it alone for a couple minutes while it loads, and then you should be able to scroll around.

Drunkard's Rock is an experiment I did to pursue a random iterative traversal of the multidimensional musical artist-similarity space.

In the mathematical version, the drunkard is allowed to retrace their steps, and in fact the point of the problem is to determine the chance of the drunkard randomly arriving home again.

In my version, retracing steps is explicitly disallowed, and thus the drunkard is doomed to wander until the universe expires. Probably it says something about my personality that this seems like the preferable curse to me.

Anyway, I started the calculation with Black Sabbath, both because my own musical evolution sort of started in earnest with Black Sabbath, and because Paul Lamere used Black Sabbath as the reference point in his inversely minded Six Degrees of Black Sabbath, which attempts to find the shortest path between two bands.

My version, to reiterate, just keeps wandering. I guess it is searching for the longest path between Black Sabbath and whatever it finds last. Except I stopped it at 100k steps, because the resulting web page is enormous enough. It will annoy you least if you just leave it alone for a couple minutes while it loads, and then you should be able to scroll around.

¶ 4 Entries for an Audible Glossary · 2 May 2014 listen/tech

Every Noise at Once is a readability-adjusted scatter-plot of musical genres. The music moves from high density on the left to high bounciness on the right, and from high mechanism at the top to high organism at the bottom. Although I do have more words to explain what each of these ideas means, it's maybe better to just hear how the qualities manifest themselves in actual music.

So here are four data-generated sampler playlists of songs that demonstrate the extreme values of these two analytical dimensions:

So here are four data-generated sampler playlists of songs that demonstrate the extreme values of these two analytical dimensions:

| Density | Bounciness |

Mechanism | Organism |