¶ The Unbearable Sadness of Pop Songs · 27 September 2013 listen/tech

In a BBC piece last week about sad music, University of Toronto professor E. Glenn Schellenberg talked about his research into sad songs over time. His observations come from the paper Emotional Cues in American Popular Music: Five Decades of the Top 40, in which he and Christian von Scheve studied (mainly) the tempo and mode of popular songs, found that over time popular songs have gotten slower and increasingly in minor keys, and equated slower and minor with sadness.

The qualitative part of this, "sadness", is fairly subjective and notoriously difficult to measure. But the quantitative part is easier. Schellenberg's study used a pretty small sample of music, though: only the top 40 songs from each year, aggregated at the decade level, and only actually five years from each decade, for a total of only about 1000 songs in the entire study.

At The Echo Nest we have key and tempo data for about 18 million songs from 1960 to 2013. I recently did a breakdown of tempo over time, in fact, and what I found from this larger sample doesn't match Schellenberg's pattern or support his contention that popular songs are getting slower.

His stronger claim, though, is that more popular songs are now in minor keys, or maybe that more minor-key songs are now popular. The paper dramatically claims that 85% of the 60s hits were in a major key, whereas only 42.5% of the hits from the 2000s were in a major key.

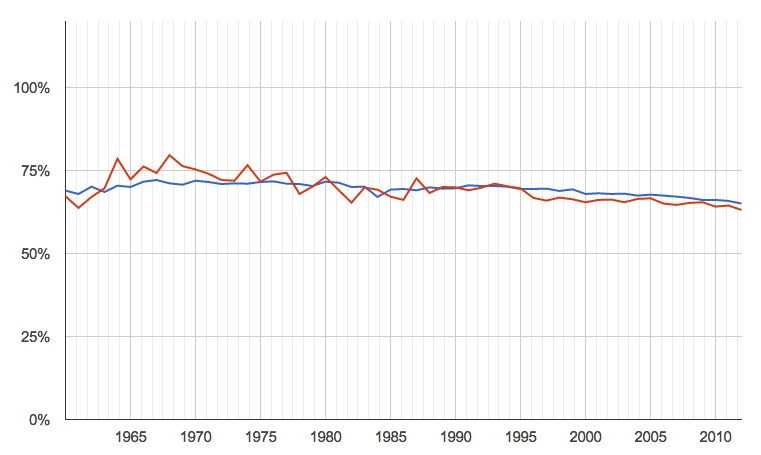

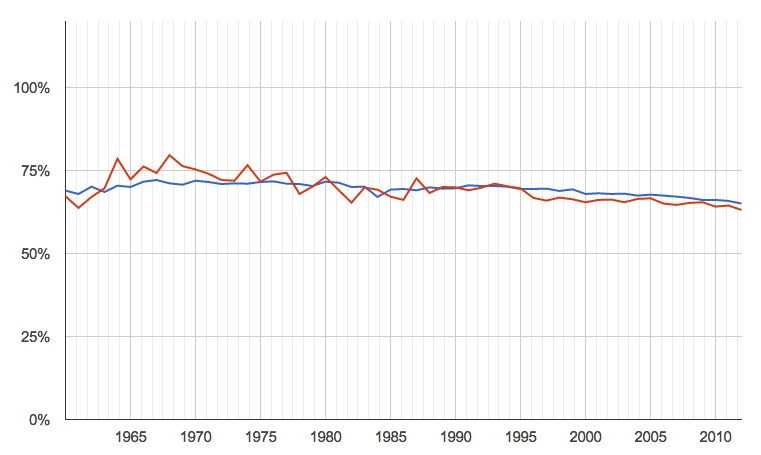

I hadn't looked at mode over time, previously, but it took only a couple minutes to run those numbers. They aren't nearly as dramatic as Schellenberg's.

percentage of songs in major keys, by year (blue is all songs for which we have data, red is just the most popular)

The recent trend is down, but only very slightly, and certainly nowhere near the dramatic 85% to 42.5% in the paper. Taking only the smaller number of most popular songs produces more variability, naturally, but not a significantly different pattern.

The saddest part of the paper, though, was not the numbers but a plaintive note that it came about in part because, in a previous study, the authors found that "clearly happy-sounding excerpts from recent popular recordings were particularly difficult to locate". If there's one thing the modern age is trying earnestly to give us, it's the ability to "locate songs". So here is a quick auto-generated list, from Echo Nest data, of maybe-happy modern popular songs. Subjectivity endures, so your reactions to any individual song may vary, but surely there is something here to extricate you from the supposedly-inexorable enveloping sadness for at least a few minutes.

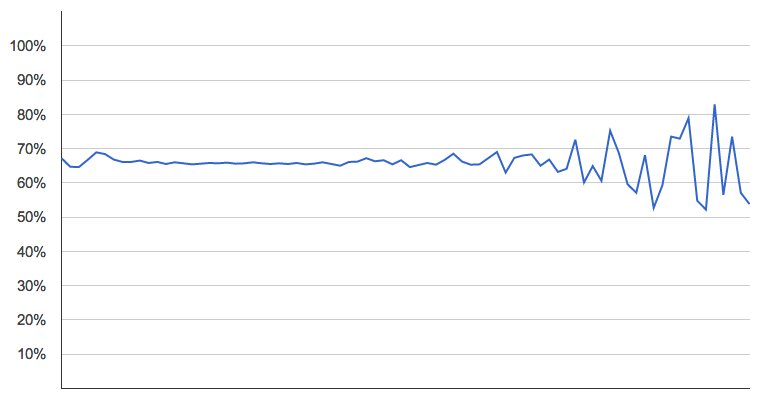

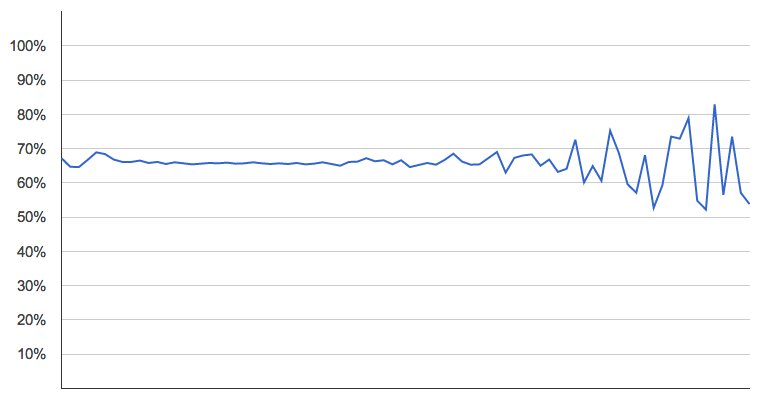

PS: Later it occurred to me to also run this analysis sliced by popularity, independent of year. That is, are current popularity and mode correlated across our entire universe of songs? No. No, they are not.

The qualitative part of this, "sadness", is fairly subjective and notoriously difficult to measure. But the quantitative part is easier. Schellenberg's study used a pretty small sample of music, though: only the top 40 songs from each year, aggregated at the decade level, and only actually five years from each decade, for a total of only about 1000 songs in the entire study.

At The Echo Nest we have key and tempo data for about 18 million songs from 1960 to 2013. I recently did a breakdown of tempo over time, in fact, and what I found from this larger sample doesn't match Schellenberg's pattern or support his contention that popular songs are getting slower.

His stronger claim, though, is that more popular songs are now in minor keys, or maybe that more minor-key songs are now popular. The paper dramatically claims that 85% of the 60s hits were in a major key, whereas only 42.5% of the hits from the 2000s were in a major key.

I hadn't looked at mode over time, previously, but it took only a couple minutes to run those numbers. They aren't nearly as dramatic as Schellenberg's.

percentage of songs in major keys, by year (blue is all songs for which we have data, red is just the most popular)

The recent trend is down, but only very slightly, and certainly nowhere near the dramatic 85% to 42.5% in the paper. Taking only the smaller number of most popular songs produces more variability, naturally, but not a significantly different pattern.

The saddest part of the paper, though, was not the numbers but a plaintive note that it came about in part because, in a previous study, the authors found that "clearly happy-sounding excerpts from recent popular recordings were particularly difficult to locate". If there's one thing the modern age is trying earnestly to give us, it's the ability to "locate songs". So here is a quick auto-generated list, from Echo Nest data, of maybe-happy modern popular songs. Subjectivity endures, so your reactions to any individual song may vary, but surely there is something here to extricate you from the supposedly-inexorable enveloping sadness for at least a few minutes.

PS: Later it occurred to me to also run this analysis sliced by popularity, independent of year. That is, are current popularity and mode correlated across our entire universe of songs? No. No, they are not.